Editor's note: This story appeared as part of the Star's Foster Farms Bowl preview, which ran on Sunday.

The numbers are astounding.

Khalil Tate rushed for 327 yards against Colorado — the most by an FBS quarterback in a single game. The Arizona Wildcats sophomore has 1,353 rushing yards in less than a full season — the most ever by a Pac-12 passer. His Total QBR, per ESPN, of 94.0 is the best in the nation — higher, even, than Heisman Trophy winner Baker Mayfield.

But Tate and his supporters take just as much pride in another figure. This one that won’t appear on any TV graphics or in any Heisman promotional materials.

Tate’s GPA is north of 3.0. The son of a teacher and a pharmacy technician is excelling in the classroom too. It’s further proof that Brian and Lesli Tate raised Khalil and older brother Akili right.

UA coach Rich Rodriguez, whose team faces Purdue in the Foster Farms Bowl on Wednesday, recalled meeting the Tates and noting how supportive they were. But they also instilled discipline in the prospect Rodriguez envisioned as a perfect fit for his offense.

The structure Khalil thrived in inspired Rodriguez to use one of his favorite phrases: “He was raised up, not jerked up.”

Lesli gives Brian most of the credit. Brian has been an educator for more than 25 years. He currently teaches third grade at Windsor Hills, a magnet school in Los Angeles.

“Our sons were raised as teachers’ kids,” Lesli said, “having great organizational skills and work ethics, ability to focus on tasks to get results, and very driven to succeed.”

Khalil said academics were “super important” in the Tate household. The message was clear: You can’t do football without school.

Independence hasn’t change that for Khalil. If anything, it has reinforced the notion that he is his father’s son.

“It’s not really hard to get good grades in college, but you gotta want to do it,” said Khalil, who’s majoring in Information Science and eSociety.

“In college, you’re kind of free from everything. If you want to do good, you’re gonna do good. If you want to have fun, it’s gonna show in your grades.”

Not that Khalil Tate is having a miserable time in Tucson; he almost singlehandedly has made Arizona football fun again.

Tate just happens to understand, at 19, the importance of having balance and staying grounded even as his career soars and his fame swells.

You don’t have to go far to find the source from which those values sprung.

Foundation set

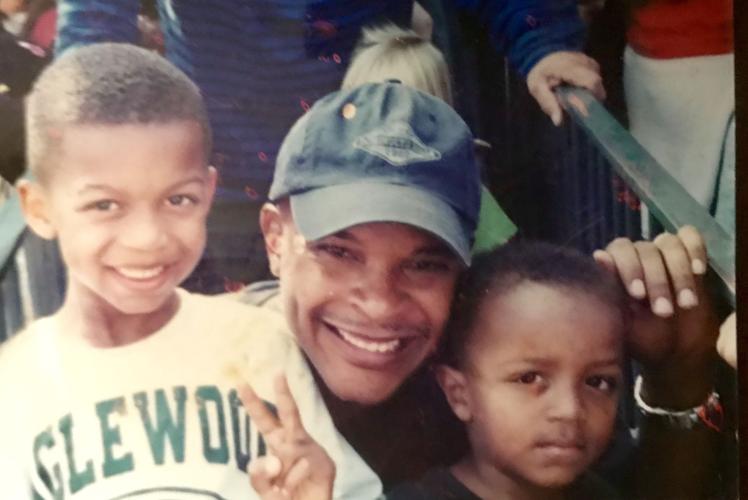

Brian and Lesli Tate were high school sweethearts in the mid-1980s. Brian attended Junipero Serra High School in Gardena, the same school Akili and Khalil would attend. Lesli went to what’s now known as Palisades Charter in Pacific Palisades. They met through one of Lesli’s cousins in 1986 and married seven years later.

Asked what it meant for Akili and Khalil to have a stable, loving home environment, Brian said: “It gave them a foundation, knowing they have two parents who will care for them, who want the best for them. It takes a burden off their back. I can be a kid. I can mature in my own time. I don’t have to rush and be a man now because my dad’s not there.”

Brian and Lesli raised their boys to be respectful, cordial, positive young men. To be humble and team-oriented. Akili, who’s three years older than Khalil, finds that approach helpful in the entertainment field, where he’s a budding filmmaker.

It certainly aids Khalil as a quarterback. As he ripped off one record-setting performance after another for Arizona, Khalil Tate consistently deferred credit to his teammates — just as his dad would have it.

“He doesn’t want to be the one that’s getting all the attention,” Brian Tate said. “He likes to be in the background. He may get that from me. I don’t like a lot of attention. I want everybody to succeed around me.”

As a quarterback, though, you have to be front and center. You have an obligation to represent and lead your team.

Perhaps because he’s so self-effacing, Khalil Tate’s teammates respond to his leadership style. He often can be seen pumping up the Wildcats’ defensive and special-teams units, offering shoulder-pad pats and words of encouragement.

“As he warms up to his team, he lets his guard down,” Brian Tate said.

“Once he gets in his comfort zone, then he’s willing to get in there and become that leader that he needs to be.”

Competitive Khalil

It’s understandable that Khalil Tate would need time to feel completely comfortable in a leadership role. He’s young for his class and was still 18 when he commandeered the QB job in early October. He’s also always been the younger brother.

When Akili started playing sports at age 5, Khalil would warm up with his brother’s teams. During T-ball games, he would go off to the side and play catch.

“If Akili had a game,” Lesli Tate said, “Khalil figured he had a game too.”

Brian’s friends were the coaches, so they would let little Khalil hit, batting him at the bottom of the order. Akili’s old uniforms would be passed down to Khalil. He’d lay one out on the floor the night before a game.

Khalil and Akili would play catch, one-on-one basketball and other games in the yard of the family’s L.A. home. The older they got, the more competitive those contests became.

“Too competitive,” Akili said. “It always ended with somebody getting upset and running into the house.”

When playing catch, one of the brothers would throw the ball too hard. The other would throw it harder. Often, something would get broken.

One-on-one would get physical. Hard fouls would be delivered. Neither Khalil nor Akili wanted to lose. Video game sessions were the same way.

The boys found an outlet in football, playing for the Jr. All American Inglewood Jets. Akili primarily played receiver. Khalil, eventually, played quarterback.

Khalil was a good athlete with a good arm. You might have heard the story about his grandma, Lesli’s mother, teaching him how to throw a football. What you might not know is that she played competitive softball as an adult. Brian’s grandfather played football at Prairie View A&M. Brian played shooting guard for Serra.

The Tate brothers had the genes and competitive spirit to succeed. Akili was a late bloomer compared to his brother and ended up playing for Hiram College, a Division III school in Ohio.

Khalil had to bide his time at talent-laden Serra. As a junior, he shared snaps at quarterback with Caleb Wilson, who would go on to play tight end at UCLA.

It wasn’t until then that Khalil’s family fully realized the breadth of his athletic ability. When he was younger, Brian said, Khalil was more of a pocket passer. “He could pass,” Brian said, “and could run if he had to.”

As a high school junior, Khalil Tate started trucking and leaping over would-be tacklers. He accumulated more than 2,600 total yards and accounted for 34 touchdowns. As a senior, he topped 4,000 yards and was responsible for 43 scores.

Even his older brother had to concede that Khalil was special.

“I realized he was on a different level,” Akili said. “I wasn’t like that in high school.”

‘Almost surreal’

The Tate brothers were sports fanatics. On those rare rainy Southern California days, or when they’d get bored in summer, they would record “SportsCenter”-esque videos.

The boys would set up four tray tables in a semicircle and drape a blanket over them, forming their studio desk. They’d get dressed up from the waist up. Akili would jot down a list of topics, ranging from Tiger Woods and the Minnesota Timberwolves’ drafting of point guards with back-to-back picks to the struggles of the hometown Lakers.

“Mitch Kupchak was the GM,” Khalil Tate said. “We used to call him ‘Mitch Cupcake.’ We didn’t really like him.”

Sometimes they would set up their “desk” in front of the TV and narrate highlights. Little did they know that Khalil one day would appear on the real “SportsCenter.”

It took patience and determination to get to that point. Tate opened this season as the backup to Brandon Dawkins. Tate then hurt his shoulder in relief in the opener.

“He had a good attitude,” Brian Tate said. “He would discuss his frustration and disappointment, but he knew if he would keep working hard he would get that opportunity. And he finally did.”

The Tates will never forget where they were on Oct. 7, 2017. Dawkins got hurt on the opening drive. Khalil Tate came off the bench. Three hundred twenty-seven yards later, Arizona had a 45-42 victory at Colorado. Khalil went viral.

Brian and Lesli watched it all unfold from home.

“We were yelling, giving high-fives, hugging each other,” Brian Tate said. “It was something. It was almost surreal.”

Akili was coming back from a job. He got caught up on Twitter. He watched the rest with his girlfriend.

“This is getting ridiculous,” Akili remembered thinking. “He’s scoring every play.”

“Everything kind of came together,” he says now. “I was just so happy for him.”

Khalil would win an unprecedented four straight Pac-12 Offensive Player of the Week awards. His profile would grow. His ego would not.

Khalil Tate has matured. He hasn’t changed.

“He’s still the same person,” Brian Tate said. “He’s just so happy that the team is having success. That’s where he gets his joy from. That’s what it’s about.”