It’s official: Stanford and Cal have accepted invitations from the Atlantic Coast Conference beginning next summer in all sports sponsored by their new home, from football and basketball to soccer, swimming and softball.

Although life in the ACC was a priority for the schools following the Pac-12’s collapse, the Cardinal and Bears will face steep logistical obstacles and have made contractual commitments that could haunt them.

“I question whether this is a good move for Stanford and Cal,” an industry source said. “But they believe it’s the right thing to do.”

You could make the case, it seems, that the schools successfully bargained for membership in the ACC’s Faustian division.

The primary reason for joining the ACC creates the greatest challenge: The athletes at each school told university leaders that they wanted the chance to compete at the highest level of college sports.

Stanford and Cal were originally rumored to be among a quartet of Pac-12 teams, alongside Oregon and Washington, under consideration for entry to the Big Ten. But as of news the morning of Friday, Sept. 1, the Bay Area schools are joining the ACC.

The Big Ten and Big 12 made more sense logistically but did not offer membership, and the SEC was never an option. Among the Power Five conferences, only the ACC extended a life raft.

“We are very pleased with the outcome, which will support the best interests of our student-athletes and aligns with Berkeley’s values,” Cal chancellor Carol Christ said.

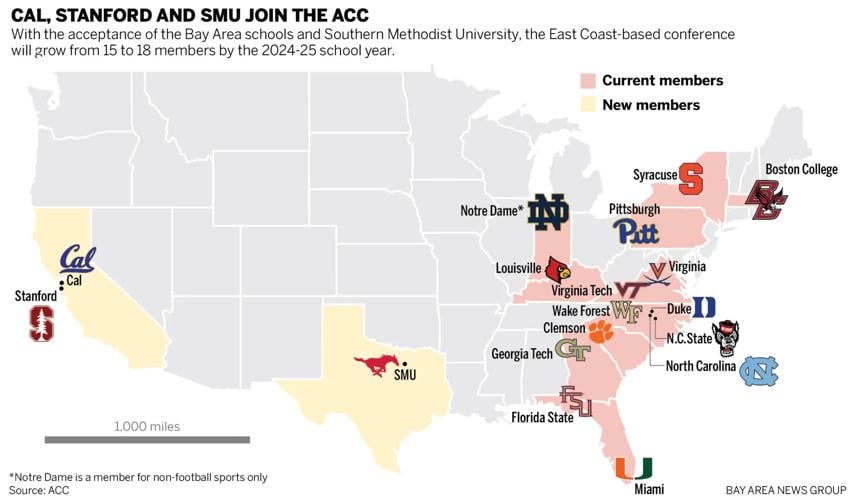

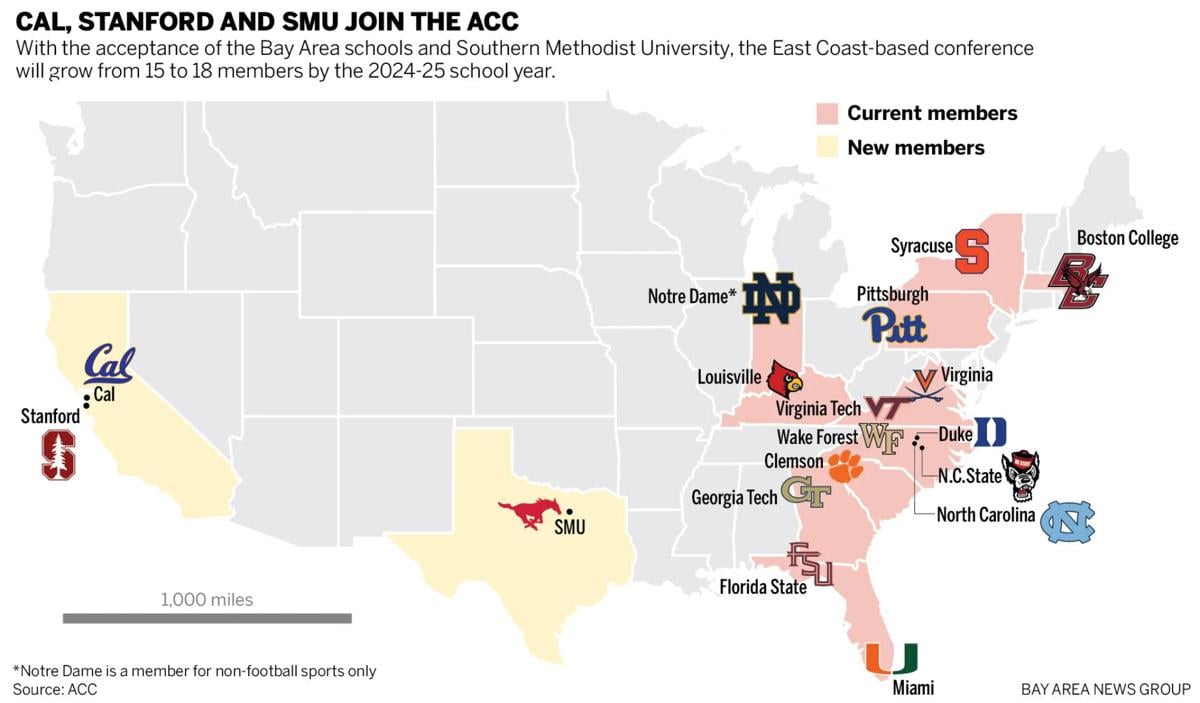

The move also works for the Bay Area schools given their large and powerful alumni bases on the East Coast. The ACC’s footprint stretches from Boston to Miami and features numerous high-end academic schools, from Virginia and Duke to North Carolina, Notre Dame and Georgia Tech.

“ACC membership aligns Stanford with a conference of leading peer institutions who share a deep history of athletic success and a commitment to the pursuit of academic excellence,” said Jerry Yang, chair of Stanford’s trustees. “We appreciate the invitation of the ACC member schools, and we are excited to join them.”

Nor are Stanford and Cal the only newcomers. SMU, which is based in Dallas, has agreed to join the ACC to create an 18-team league. (Notre Dame competes in all sports except football.)

SMU’s presence could allow the conference to schedule neutral-site games that would reduce travel demands for the teams located on both coasts.

According to Stanford, more than half of its sports (22 of its 36) will experience “either no scheduling changes or minimal scheduling impacts.”

But for the others, the travel impact could be severe. There’s simply no way around scheduling multiple trips to the East Coast for conference competition in men’s and women’s basketball, for example.

Logistically, Stanford and Cal competing in the ACC makes even less sense than USC and UCLA competing in the Big Ten.

What’s more, the Bay Area schools are contractually bound to the ACC until the conference’s grant-of-rights agreement with ESPN expires — in 2036. That’s an eternity in the rapidly changing landscape of college sports.

Yes, the long-term contract provides stability for the Cardinal and Bears. It also takes them off the market.

If another round of realignment strikes at the end of the 2020s and the Big Ten wants to increase the size of its western arm, Stanford and Cal would not be available to join USC, UCLA, Oregon and Washington.

“Do you really want to lock yourselves in for 12 or 13 years?” the industry source said. “That’s two or three generations of students. You might miss an opportunity.”

What’s more, Stanford and Cal are bound to the ACC until 2036 at discounts. They have agreed to take partial revenue shares from the conference’s media rights deal with ESPN.

Cal offered insight into the financial arrangement in its official statement on the move:

“The university will receive a full share of all revenues, including media revenue, while contributing back a portion of its media revenue to support and strengthen the conference and its current member institutions. UC Berkeley’s membership contribution will taper off until the 10th year, at which point it will begin retaining 100% of its media revenue share. The fact that annual revenue will increase over time was an important factor in the agreement.”

(Stanford’s deal is expected to be similar, if not exactly the same.)

What does it mean in raw dollars? The contract is not public, but over the course of the contract, the Bears and Cardinal could receive $10 million to $12 million less per year, on average, than the current ACC schools.

That could create a substantial competitive disadvantage when it comes to critical resources like recruiting budgets and the salary pool for coaching staffs.

Stanford will seek help from the university administration and its wealthy donor base.

Cal could receive assistance from the UC regents, who have the authority to impose a so-called Berkeley tax on UCLA by which the Bruins would use some of their revenue from Big Ten membership to support Cal.

Will the Bears cobble together enough cash to support all their Olympic sports? The athletic department already receives more than $20 million per year in aid from central campus.

“While I get that this is the deal they probably have to do,” said a source with ties to the Bay Area schools, “I have zero excitement about it.”

Pac-12 commissioner George Kliavkoff delivers his opening address and takes questions from media on hand in Las Vegas Friday, July 21, 2023 as part of Pac-12 football media day. Video courtesy Pac-12