Nick Gonzales wakes up at 7 a.m. most days, shuffles to the kitchen, cracks three eggs — sometimes four — and cooks them over easy. He slathers avocado spread on a piece of toast, and begins his day.

Normally, Gonzales — a Tucson native and star infielder at New Mexico State — would then drive to his Las Cruces campus for class and a 4 p.m. practice. He’d stay late to get some hitting in, maybe do some homework, and get home late. Gonzales had the daily routine down cold, and, frankly, it was working.

The Cienega High School product is widely considered one of the top prospects available in the upcoming MLB Draft. In its first mock draft, CBSSports.com projects Gonzales going No. 2 overall to the Baltimore Orioles. MLBDraft.com says he’ll be taken fourth overall by the Kansas City Royals. ProspectsLive.com has the Toronto Blue Jays drafting Gonzales fifth overall, and BaseballProspectJournal.com has him going sixth to the Seattle Mariners.

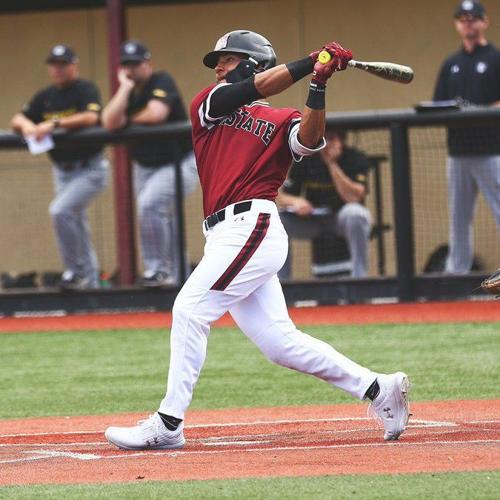

It’s easy to see why pro scouts love him. A year ago, Gonzales was a first-team All-America selection. He entered 2020 as the first athlete in New Mexico State history to receive unanimous preseason All-America honors. He started the season on fire, belting 12 home runs and driving in 36 runs though 16 games when spring sports were canceled due to the coronavirus. Gonzales was on pace for 40 home runs and 119 RBIs, which would’ve been the best college season by any player at any level since 2003.

Missing out is “an empty feeling, just because you were supposed to do all this stuff and play all these games and compete, that’s what you looked forward to for an entire year,” Gonzales said.

With his collegiate career essentially over — he can return for his senior season at NMSU, but likely won’t — Gonzales has been preparing for the June 10 draft with a routine that feels similar. The infielder trains at an off-campus baseball oasis in Las Cruces with former Aggies teammate Joey Ortiz, who’s currently in the Baltimore Orioles organization, and NMSU assistant coach Mike Bernal. His school work is being done online.

That Gonzales is so close to achieving his pro baseball dream is a testament to his work ethic — and the result of a decision he made as a Cienega senior.

This is his story.

Nick Gonzales, right,, shown in 2016, put up big numbers at Cienega High School, but didn’t receive much attention from colleges. He quickly proved them wrong at NMSU.

‘That was his thing’

Gonzales’ upbringing was structured, disciplined — and yet balanced. His parents, Mike Gonzales and Jill Bosland-Gonzales, made sure of it.

Mike, a former Santa Rita High School baseball standout, coached Nick from the time he could first play until he left for New Mexico State in 2017. Jill, also a Santa Rita grad, was the nurturing, tender mother that kept the household together.

Mike Gonzales loved baseball’s Yankees and football’s Cowboys, and Nick Gonzales followed suit.

They preferred Alex Rodriguez, New York’s often controversial third baseman, over Derek Jeter, the club’s clean-cut captain.

“That was our guy and favorite player — his swing and his swag. He got into a little bit of trouble, but we still respected him and he was still one of my favorite players,” Nick Gonzales said.

Nick’s older brother, Daniel, was a multisport star at Cienega who led the Bobcats to a state football championship appearance in 2011 as a linebacker before playing collegiately at Navy. Nick and Daniel have a younger sister, 14-year-old Faith.

Nick Gonzales wasn’t like other millennials during his childhood. He wasn’t consumed by video games or pop culture trends.

His hobbies?

“Uh, baseball,” Mike said with a laugh. “That was his thing. He was into a yo-yo for a short period of time. … But he’s just an extremely focused young man. He doesn’t party. He doesn’t drink. He’s just focused on baseball.”

Like his brother, Gonzales thrived by playing two sports. The fall was for football, and baseball filled in the cracks on the calendar. That lated until high school, when he realized baseball fit him better.

“Football is kind of a pain,” he said. “I really hated practice.”

Around that time, Gonzales had a new coach. Mike backed off, putting him in the hands of former Pima College and UA star George Arias, a former major-leaguer.

Arias coached Gonzales at Tucson Champs Baseball Academy from the time he was 12 until his final season at Cienega. The coach began by changing Gonzales’ position, moving him away from catcher. Gonzales would play second base, shortstop and center field.

Gonzales was too talented offensively, Arias believed, to play behind the plate.

“‘How many five-tool catchers,” Mike Gonzales said, “do you see in Major League Baseball?”

‘I’m gonna prove them wrong’

When Mike coached his oldest son, Daniel, in Little League, Nick Gonzales was off in the neighboring batting cage hacking away baseballs off a tee, one bucket after the other.

“Nick was probably 6 or 7 years old and he’s hitting off the tee during games,” Mike said. “We’re playing our game and Nick is in the cage. He’d hit a whole bucket, pick them up and do it again during games.

“One of the parents came up to me and was like, ‘You’re so mean, you’re making your kid do that during games. Let him play.’ I turned to them and said, ‘What are you talking about?’ They said, ‘Your youngest son is in there hitting during games.’ I just started laughing and told them that had nothing to do with me. That’s just what he does. He just wants to hit, and that hasn’t changed. Obviously I don’t know everybody, but I’ve never seen any player hit as much as that kid does.”

Father and son bonded over their passion for baseball, with Mike pitching batting practice to Nick. Eventually, Nick wore down his father’s arm to the point where he couldn’t do it anymore.

“There were days when I would stay at work late just so I could get out of it, because my arm was hurting so much. I’m like, ‘Dude, I can’t go today, I just can’t do it,’” Mike said.

That work ethic followed Gonzales to Las Cruces. Two weeks before his junior season at New Mexico State, the Aggies held a nine-inning scrimmage. Gonzales played the entire game at shortstop, then stayed to take extra batting practice. Gonzales had suffered a wrist injury, and felt the need to make up for lost time.

New Mexico State hitting coach Mike Pritchard witnessed it first-hand. He returned to the field 90 minutes after the game with his dog to find Gonzales still “in the batting cage by himself with the lights on,” he said.

“I’m standing there like, ‘Dude what are you doing?’” he said. “He said, ‘Uh, I missed last week so I gotta get back in the cage.’

“I asked him, ‘How many swings are you going to take?’ He goes, ‘I don’t know, probably 1,000,’ and then I started laughing. But then I realized, ‘This guy might actually take 1,000 swings right now. This is after playing nine innings at shortstop and (taking) five at-bats during the game while also coming off a wrist injury. I’ve never seen anybody like this or know anybody like this. It separates him from everybody else.”

Proving doubters wrong has always fueled Gonzales, which is primarily the reason he walked on at New Mexico State following a stellar career at Cienega. Austin Peay in Clarksville, Tennessee, offered him a 98% scholarship. Gonzales’ measurables — even now, he’s listed as 5 feet 11 inches and 190 pounds — didn’t quite put him on the Pac-12 level.

New Mexico State coach Brian Green, now at Washington State, told Gonzales he could join the Aggies as a walk-on. Take it or leave it. Gonzales chose the challenge over the (nearly) full ride.

“He goes, ‘Honestly, they don’t think I’m any good. I’m gonna prove them wrong,’” Mike Gonzales said. “Those were his exact words.”

Nick Gonzales

Walk-on no more

Las Cruces provided Gonzales with the fresh start that he didn’t know he needed. He arrived at NMSU not knowing anyone; his parents, family members and coaches were in Tucson, hundreds of miles away.

“There were no expectations for me to do whatever,” he said. “I had my own expectations.”

Gonzales scratched his way to the starting lineup as a second baseman, appearing in 57 games and earning WAC Freshman of the Year honors and a Freshman All-America award.

New Mexico State soon awarded him a scholarship.

“It was the best decision of my life to come here,” Gonzales said.

As a sophomore, Gonzales emerged as one of the top players in college baseball.

Gonzales put together one of the best offensive seasons in New Mexico State history, belting 16 home runs with 80 RBIs, 19 doubles and four triples. His .432 batting average was tops in the country. He finished third nationally in slugging percentage, fourth in hits and fifth in both RBIs and on-base percentage.

Six baseball publications named Gonzales to their All-America teams.

Of course, not all good players are pro prospects. Gonzales was criticized for playing at a Western Athletic Conference school and specifically at NMSU, where high altitude and friendly dimensions — the left-field wall at Kyle Askew Field is 345 feet from home plate — made for a hitter’s dream.

Gonzales wasn’t included on MLB mock drafts until after he was named MVP of the Cape Cod League, a summer showcase of the top collegiate baseball players, following a successful season with the Cotuit Kettleers. In 153 at-bats, Gonzales hit .351 with seven home runs.

“The best of the best are there,” he said. “If you do really well over there, it shows. … It helped me a ton and showed that I can actually hit and perform outside of my school and conference.”

Gonzales switched to shortstop for his junior season, and led the Aggies with 52 putouts in his shortened junior season. He also turned eight double plays. Offensively, Gonzales extended the nation’s longest-active on-base streak to 82 games. In February, he mashed five home runs in a doubleheader against Purdue-Fort Wayne.

“I’ve never seen hands like that in my life. … I’ve seen a lot of guys who made it to the big leagues and his hands are just so lightning fast, it translates,” Pritchard said, who compared Gonzales to Red Sox second baseman Dustin Pedroia and Cubs outfielder Kyle Schwarber.

“Is he going to hit 50 home runs in the big leagues? I don’t know, maybe. But the way he swings the bat is next to nobody I’ve ever seen before.”

Before the 2020 season was cut short, Nick Gonzales hit five HRs in a doubleheader.

Staying in touch

While he waits for the draft, Gonzales is focused on training. He has turned to a familiar face, Cienega strength and conditioning coach Steve Schween, for help.

“He came back home,” Schween said. “He trusted and believed in what we do.”

Every day, Gonzales fills out a questionnaire about his sleep schedule, hydration, meals and stress. Schween reviews the results and adjusts his workout plan. Schween built Gonzales a personalized workout calendar on TeamBuildr, a training app utilized by college and pro teams.

“I’m just focused on getting stronger and building my speed and strength. Working on that every day is going to help get ready for the next level,” Gonzales said. “All the guys at the next level are stronger and older, so I’m focusing on building strength but keeping the speed and flexibility. Movement is super important in the position that I play.”

‘A dream come true’

Gonzales’ hard work is about to pay off. The No. 2 overall pick comes with a slot value of $7,789,900. The Royals’ pick is slotted at a value of $6.6 million, while the Blue Jays’ pick is slotted at $6.18 million.

Gonzales plans to pump some of his money back into his hometown.

“I want to buy a home gym,” he said. “I want to have a shed with a tunnel and batting cage in it and a really nice gym. That way, all my buddies can lift and work out, and I can go there to train so I don’t have to deal with going anywhere else. It’ll be right there by my house. I don’t know how much it’ll cost.”

It’s a good bet that Gonzales will join local royalty on draft day. Just two Southern Arizona high school products have been taken in the top 10 of a draft: The Minnesota Twins selected former Tucson High and UA star Eddie Leon ninth overall in 1965, but he did not sign. The Pittsburgh Pirates picked Sahuaro High School’s Sammy Khalifa seventh in 1982. No Tucson player has ever been drafted in the top five.

Gonzales could be the first.

“It’s a dream come true, for sure,” Gonzales said. “Coming from a small town, I’m trying to help out all the other guys from (Tucson) and show them that it can be done, and you don’t always have to be the highest recruit out of high school, you can still make a name for yourself. If the U of A doesn’t want them, or if ASU doesn’t want them, they can make a name for themselves somewhere else.”