Ricky Hunley texted his daughter Alexis last week. Where are you? Are you safe?

Alexis Hunley, a photographer, was at the center of Black Lives Matter protests and demonstrations near Hunley’s home in downtown Los Angeles. A reporter for Time magazine asked Alexis what prompted her to be part of a crowd estimated at 25,000.

“The love I have for every black person who has marched, protested and organized — past, present and future — is what’s keeping me together,” she told the magazine.

Earlier that evening, Ricky and his wife, attorney Camille Moore-Hunley, were watching the sobering television documentary about the 1992 Los Angeles riots.

“Racism has been part of my life,” says Hunley, an All-America linebacker at Arizona in 1982 and 1983 and a 1997 inductee into the College Football Hall of Fame. “People are tired of it; fed up. My mom detested it, stood up against it and said what she believed.”

A year before Hunley was born in Petersburg, Virginia, the Petersburg City Council voted to close Wilcox Lake, one of the area’s most popular recreation venues, because it did not want black people swimming there. White people were not allowed to use the lake either, but the greater goal was to keep black people out.

Petersburg was 80% black, then and now. Most of the white people of Petersburg lived in the Colonial Heights suburb.

“When a black family moved into Colonial Heights, they would often burn a cross on their lawn,” remembers Hunley, 58, who is now a sales executive for Outdoor Media, a national advertising firm that also employs former Wildcats David Wood and Doug Penner.

Over those 58 years, Ricky Hunley has witnessed just about every variable of American society, good and bad, from playing in the Super Bowl and coaching in the NFL to finding Confederate bullets and Civil War artifacts buried in an old battlefield near his mother’s home.

In the late summer of 1983, I had the pleasure to meet Ricky’s mother, Scarlette, at her home in Petersburg. She welcomed me into her home, no more than a mile or two from the Petersburg National Battlefield, where in 1864-65 one of the most horrific battles of the Civil War — the 292-day siege of Petersburg — effectively led to the surrender of the Confederacy.

About 5,000 people died at the Petersburg National Battlefield, which is about 70 miles from Appomattox, where Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant.

I spent much of the day at Scarlett’s home, meeting many of her 11 children and some of the 56 foster kids she helped raise while working for the Virginia state social services department. I filled my notebook with childhood stories about Ricky and his younger brother, Lamonte, an All-Pac-10 linebacker at Arizona in 1984 who now owns a fitness equipment business in Tucson.

But what stayed with me was how much life in Petersburg, Virginia, was different from the life I had known growing up in Utah and living in Arizona.

There was not a single black person in my high school. I did not meet or talk to a black person until I entered college in 1970. It was as if the Hunleys and the Hansens grew up in different worlds.

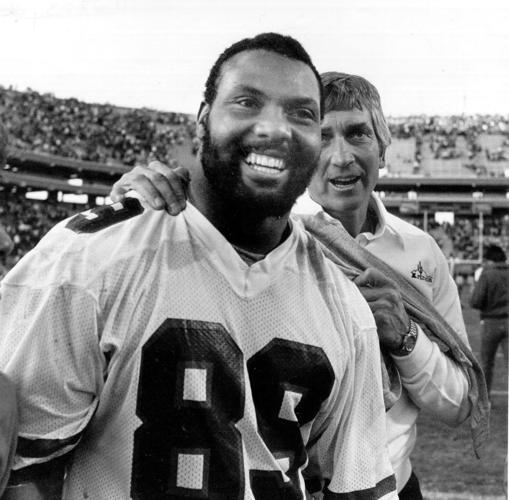

Ricky Hunley and coach Larry Smith celebrated Arizona’s 17-15 win over Arizona State in Tempe in 1983. Hunley said that before his football skills made him a top recruiting target, his dream was to climb the ranks in the Army.

As Scarlette made lunch for us that day, Ricky’s siblings told me stories about their beloved grandmother, Annie Mae Goode, and how she had worked for a white family in Colonial Heights.

“My mom hated it when she had to pick grandma up after work,” Ricky remembers. “They would only let her go through the back door. It was all ‘yes, sir, and yes, ma’am.’ I didn’t like it any more than my mother did.”

That was 50 years ago. No wonder Ricky Hunley says he’s tired of racism. No wonder Scarlette’s granddaughter, Alexis, is moved to attend Black Lives Matter protests.

One of the biggest regrets I have over all the years in this business is that Scarlette Hunley was unhappy with the piece I wrote about her son after the day at her house in 1983.

I wrote that Ricky’s grandmother, Annie Mae Goode, stayed in the “slave quarters” behind the main portion of the Hunley house. It was insensitive and out of place. When Scarlette flew to Tucson later that fall to watch Ricky play in his final game at Arizona Stadium, I lingered by the locker room in attempt to see her.

When Scarlette saw me, she was visibly upset.

“You embarrassed my mother when you wrote that she slept in slave quarters,” she said. “You embarrassed all of us.” She walked away.

Every time I’ve seen or talked to Ricky over the years, I’ve thought about that. It doesn’t go away, especially now, given the racial unrest of the last few weeks.

When I told him about it the other day, Ricky told me to forget it.

“I experienced racism in Tucson,” he said. “When a white girl at the UA I wanted to date told her dad, he slammed a framed picture of me against the wall. But I had so many white friends in Tucson — (former UA basketball player) Warren Rustand and his family, Judge Stanley Feldman, people who influenced me as much as anyone in my life. I mean, I even went camping with the Rustand family. I had never gone camping in my life.”

Ricky Hunley UA All-American

It was progress for a young man with a big personality from Petersburg, Virginia.

As a teenager, before his football skills made him a preferred recruiting target of Notre Dame and Ohio State and a future first-round NFL draft pick, Hunley dreamed of being a five-star general in the Army. He grew up near the military base at Fort Lee, Virginia, and, besides, he says, “for many of us, that was our only way out of Petersburg.

“Do you know what the biggest event of the week was?” he added. “It was when my mom got her welfare check; one lucky kid got to go shopping with her that week.”

Things soon changed. A few years after Hunley left Arizona, he bought Scarlette a 14-room house in Petersburg. Scarlette was soon elected to the state Welfare Advisory Board. Ricky’s sister, Renita, became communications supervisor of the Petersburg Bureau of Police.

In 1991, as his playing days ended, Ricky married Camille Moore, whose father, Judge H. Randolph Moore, was a Supreme Court Judge for the state of California. Camille has gone on to become an attorney for the California Department of Fair Housing and Employment. Their daughter Kenady, a USC grad, also works for the state Department of Fair Housing and Employment.

The Hunley family has moved far beyond the day the Petersburg City Council closed Wilcox Lake.

“I grew up sleeping five kids to a king-sized bed — me, Lamonte, Kevin, Quinton and Derek,” Ricky says. “When you grow up poor in the projects, you do what you got to do. But that doesn’t mean you have to stay in the projects. That doesn’t mean you can’t make a better life for yourself. Things have to change to make life better for everyone.”

In 2012, Scarlette Hunley was selected to the Florida-based Biltmore Registry’s “Who’s Who” for her work in the Petersburg community. “I want to inspire others that their lives can change,” she said. “And that they do not have to accept what others tell them as truth.”

And in 2018, after 48 years of inaction, the Petersburg City Council voted to reopen Wilcox Lake to all people.