The envelope from Arizona football coach Warren Woodson was addressed simply:

Mr. Don Bowerman

Route 10, Box 807

Texarkana, Texas

Woodson’s letter was to the point. “Our scholarship committee has ruled that you must be in the upper half of your class to gain admission to Arizona. Have your transcripts mailed directly to me. Call me collect at 3-6955, extension 323.”

This was April 1953 and an 18-year-old Texan faced such an uncertain future that the possibility of playing football at Arizona seemed like a dream.

“I didn’t like the racial activity in Texarkana,” Bowerman remembers. “The KKK was visible. Black people were required to sit in separate areas of the football bleachers and movie theaters.”

The son of a man who built railroad ties and telephone poles, Don Bowerman had been “discovered” by one of Woodson’s former players at Texarkana Junior College. Bowerman was a physical running back and baseball standout; he did not want to get stuck on the Arkansas-Texas border, where racism was so prevalent that the three high schools in town were strictly divided: one for white students, one for black students, another for Catholics.

The lure of creating a new life for himself was powerful.

Arizona baseball coach Frank Sancet also wrote Bowerman a letter. “We are one of the few schools that allow our boys to play football and other sports,” he wrote. “We flatter ourselves that we have one of the best athletic plants in the country.”

So in the summer of 1953, Don Bowerman of Route 10 in Texarkana, Texas, filled a duffel bag and walked to Highway 80 and began to hitchhike. Destination: Tucson. It took two days before he was dropped off at the Greyhound bus terminal in Mesa.

If you think today’s Arizona athletes — golfers from Taiwan, swimmers from Croatia, women’s basketball players from Latvia and Spain — face an uncertain future given the coronavirus pandemic, imagine what it was like for Bowerman standing alone on a back-road Texas highway before he was old enough to vote.

A few months earlier, one of Woodson’s assistant coaches, Vane Wilson, made an unannounced stop to see Bowerman. He brought a UA yearbook and a copy of the Daily Wildcat. Even though he would never see or speak to Wilson again, Bowerman liked what he saw.

His only other offer was from small-school Stephen F. Austin of Nacogdoches, Texas, which was as racially charged as Texarkana.

“I never thought of going back to Texarkana,” says Bowerman, now 84 and living in a senior community complex on East River Road. “I am from a very poor family. No one had finished high school and I had a burning desire to go to college. So I saved money, hitchhiked to Tucson and fell in love with the desert and a local girl.”

Bowerman’s career in Tucson became something of a fairytale compared to those he left behind in Texarkana. He is powerful evidence that Americans can overcome not just COVID-19 but what can seem like insurmountable odds.

But there was nothing magical or easy about his success.

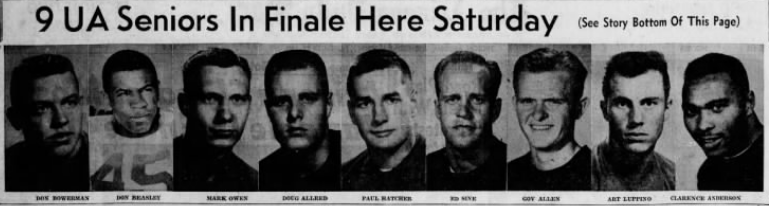

The role Bowerman hoped to play at Arizona — featured running back — vanished when a fast and elusive halfback from San Diego, Art Luppino, “The Cactus Comet,” arrived for first training camp. Bowerman’s hoped-for spot on Sancet’s baseball team was lost when Woodson told him he would lose his scholarship unless he proved himself again in spring football drills.

Don Bowerman, far left, moved to defense after losing his starting tailback job to Art Luppino, Arizona’s famed “Cactus Comet.”

Playing football at Arizona in the mid-1950s was nothing like it is today. The roster was often rewritten with ex-servicemen returning from the Korean War who were recruited over those already on the roster. Bowerman, who is white, witnessed racism at its worst while with the Wildcats. While on trips to Texas Tech and UTEP, the UA’s black football players were banned from sleeping in the team hotels and eating in the same restaurants.

Bowerman became close friends with UA lineman Ed Brown, who would go on to become the first black head coach of a high school team in Tucson, at Cholla High School in 1969. They worked together, young coaches as Pueblo High School became a state football power in the ’60s.

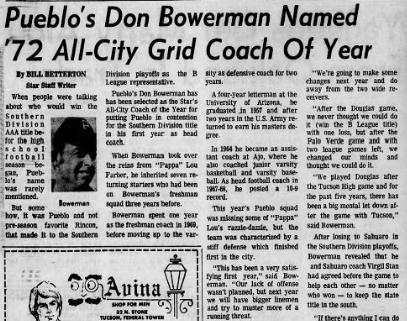

When Bowerman developed a desire to be a head coach, he left Pueblo to coach football at remote Ajo High School. Talk about paying your dues. A few years later he became Pueblo’s head coach, a job he held until the end of the 1976 season. In 1972, he was Tucson’s high school football coach of the year.

But that’s only half of Don Bowerman’s success story in Tucson. While at the UA, he met a local girl, Bella Marie Jacobs, who he married in 1957. Then he was inducted into the United States Army and sent to Germany.

Once he was honorably discharged, Don and Bella Bowerman returned to Tucson and became career school teachers, raised five children, and lived a wonderful life. Bella died in 2014.

As he looks back across his improbable journey from 1950s Texarkana to 21st century Tucson he uses three words — “pure unadulterated luck.”

If you are feeling overwhelmed by today’s extraordinary challenges, do yourself a favor. Think about Don Bowerman hitchhiking to Tucson 67 years ago, determined to find a better life.