Editor’s note: Star columnist Greg Hansen is profiling 10 times that Tucson teams beat No. 1. Today: Lute Olson-coached Team USA’s win over the Soviet Union in the 1986 FIBA World Basketball Championship.

Injured and on crutches, Steve Kerr was sitting on his couch Sunday afternoon, July 20, 1986. The next day, Kerr would undergo surgery to repair a torn ACL at St. Mary’s Hospital.

As he began to watch a tape-delayed broadcast of Team USA’s stunning upset over the Soviet Union to win the 1986 FIBA World Basketball Championship, Kerr had no idea that Lute Olson’s team had won the USA’s first world title since 1952.

Kerr asked his mother, Ann — visiting Kerr’s Tucson apartment from Los Angeles — not to tell him or his brother the game’s outcome, played eight hours earlier.

Kerr had left Madrid, Spain, 48 hours before the championship game after tearing his ACL with 4:03 remaining in a rousing semifinal victory over Brazil. UA assistant coach Scott Thompson and Brazil’s global basketball star Oscar Schmidt carried Kerr from the court.

“We helped Steve into the locker room where the team doctor told Steve that it could be a career-ending injury,” remembers Thompson, now a Tucson wealth management advisor for UBS Financial Services.

Thompson paused for effect. “That sure went over well,” he says.

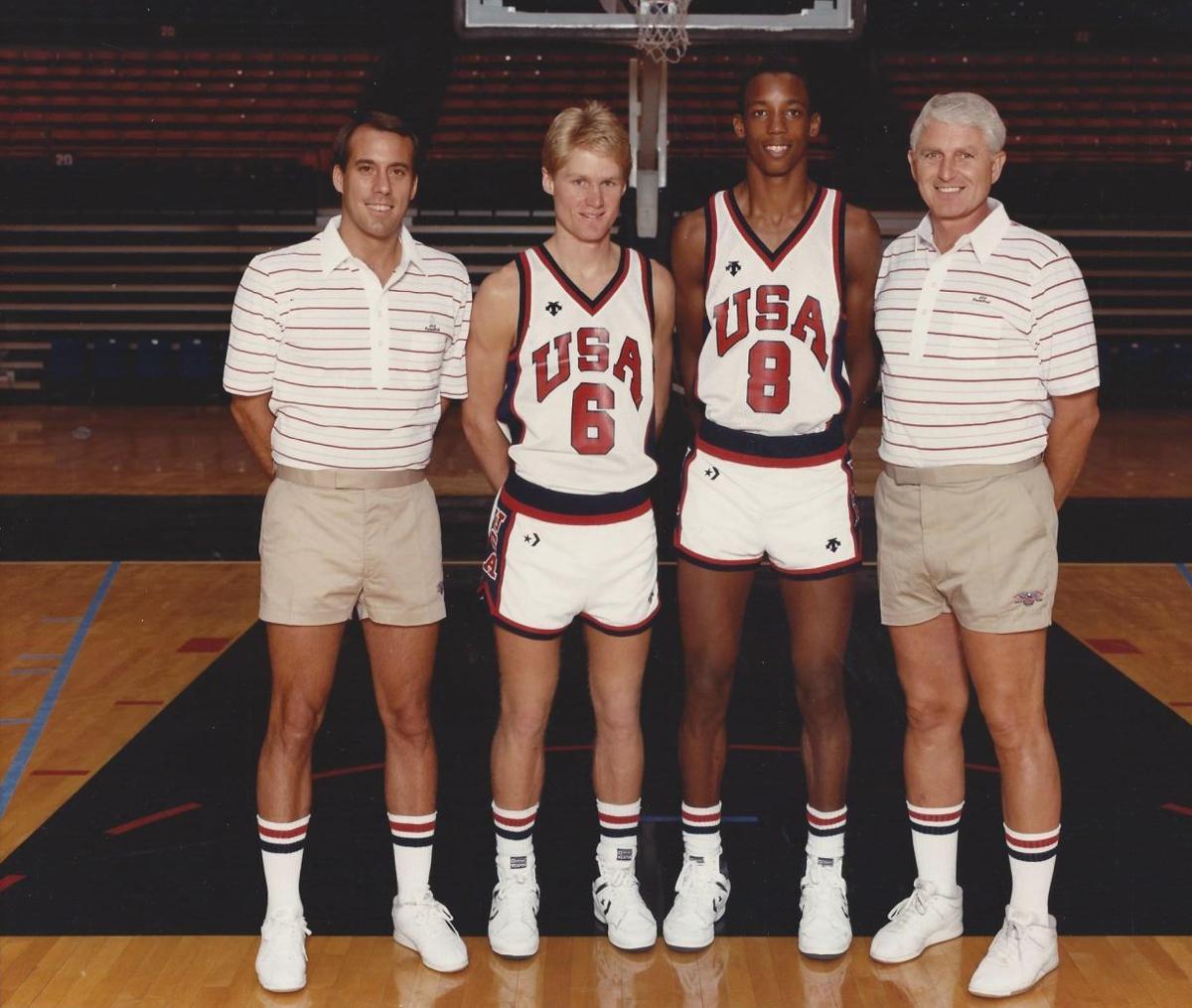

Recovering from knee surgery, Steve Kerr gets a visit from UA coach Lute Olson and teammate Sean Elliott at the St Mary’s pediatric ward on July 22, 1986. Olson awarded Kerr, who was on the USA Basketball team, with the gold medal from the FIBA World Basketball Championship.

On the bus back to the team hotel that night, I walked past Kerr, sitting alone in a front seat, wiping away tears.

When Prince Felipe of Spain placed gold medals around the necks of Olson, Thompson and Wildcat sophomore Sean Elliott in a joyful postgame celebration, Kerr could’ve had no idea that (a) he’d ever play basketball at an elite level again, (b) lead Arizona to the nation’s No. 1 ranking and the 1988 Final Four and c) go on to win eight NBA championships as a player and coach.

“It was a special time,” says Thompson, who went on to be the head coach at Wichita State, Rice and Cornell. “It’s even more special when you look back and see all that Steve overcame after he was sent back to the United States before we played Russia.”

What was equally remarkable was that Kerr was even part of the USA’s surprise winner of the world championship. After his junior season at Arizona, Kerr was somewhat of a longshot candidate among 48 players invited to Team USA’s training camp in Colorado Springs.

Not only that, Kerr became the fourth-leading scorer for Olson’s championship team, averaging 10 points per game and shooting 56%, the team’s most feared shooter and ball distributor.

When Olson, Thompson and fellow assistant coaches Jerry Pimm of UC Santa Barbara and Bobby Cremins of Georgia Tech arrived for a four-day tryout camp in Colorado Springs, the big-name guards among 48 collegians were UCLA’s Reggie Miller, St. John’s Mark Jackson, North Carolina’s Kenny Smith, Georgetown’s Reggie Williams and Duke’s Tommy Amaker.

Wake Forest guard Muggsy Bogues, who became one of the team’s four guards, admitted that he had never heard of Kerr before meeting him at training camp.

“Out of the original 48 we invited to Colorado Springs, we got maybe four of the ones we really wanted,” Olson told me on that July night at the Madrid Sports Palace, a gold medal hanging above the USA emblem on his shirt.

The process of selecting 12 elite players fractured when NCAA championship center Pervis Ellison of Louisville didn’t seem enthused about going through the tryout process, and when Kansas All-American Danny Manning was injured and couldn’t play. Indiana All-American point guard Steve Alford chose not to participate.

“We discussed the potential roster makeup every night and it wasn’t easy,” says Thompson. “We just had a bunch of young guys. A gold medal was the goal, but it’s probably good that we didn’t know what we didn’t know.”

Such as: how good world powers Russia and Yugoslavia were with such future NBA standouts as Arvydas Sabonis and Drazen Petrovic.

Olson and his staff ultimately chose a squad whose average age was 19ƒ. The Russian team’s average age was 23½.

One of Olson’s most eye-raising choices was to select team-chemistry players like Bogues, Amaker, Smith and Kerr as his four guards rather than the more high-profile Miller, who had led the Pac-10 with 25 points per game that season.

On the first day of training camp, I asked Olson about Miller’s chances to make the team. Olson was typically upfront, saying “we want to see him play defense and give up the ball.”

Miller didn’t make the cut.

“It wasn’t that controversial,” Thompson remembers. “I give so much credit to Lute; he was able to put together a team that could play to its maximum abilities in a short time.”

Team USA moved to Tucson to train for three weeks in June. On June 23, a week before flying to France, Team USA played New Zealand’s national team in an exhibition game at McKale Center. The 12,409 who almost filled the arena quickly saw why Kerr made the team.

With 18:03 remaining in the second half, Kerr swished a 16-foot jumper.

With 17:23 remaining, Kerr buried a 3-pointer.

With 16:46 remaining, Kerr hit another 3-pointer.

And with 16:14 remaining, Kerr again swished a 3-pointer.

The public address announcer at McKale Center almost became hoarse delivering his trademark “STEEEEVE KERRRRRR!” exclamation after every Kerr basket. Team USA won 112-49. Kerr had been discovered.

Navy center David Robinson, who would go on to be the MVP of the world championships, said “Kerr’s a leader. You can expect to see a lot of him in Spain.”

Said Kerr: “I never felt like I had a lock on making the team. I felt good about it, however.”

After playing two exhibition games in France, Team USA flew to the Mediterranean coast town of Malaga, Spain, and clobbered West Germany, Ivory Coast and Italy. It survived an off night, beating Puerto Rico, 73-72.

Then it was off to small-town Oviedo, Spain, where they lost to Argentina, 74-70, but rallied to whip Canada and upset Yugoslavia, coached by former BYU All-American Kresimir Cosic.

As it moved to Madrid for the semifinals, Olson’s team came together. Pitt power forward Charles Smith led the team in scoring with 15 points per game. Smith, a clutch shooting guard, averaged 14, Robinson 12 and Kerr 10. Alabama’s Derrick McKey, UNLV defensive stopper Armon Gilliam and Arizona’s Elliott rounded out the rotation.

It wasn’t like “The Miracle on Ice,” the USA’s hockey gold medal victory over Russia six years earlier, but it was close.

It was pros against college kids.

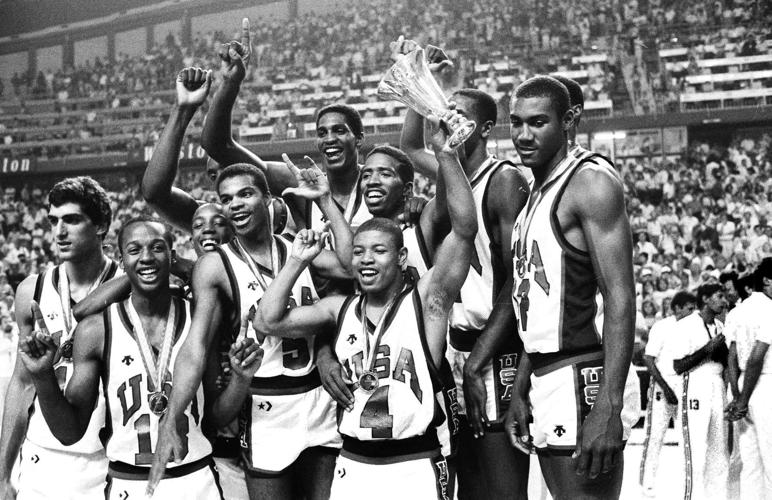

Muggsy Bogues and his Team USA teammates celebrate their 87-85 victory over the Soviet Union in the 1986 World Basketball Championship finals. Bogues and UA’s Steve Kerr made the roster over UCLA’s Reggie MIller.

“The Russians were really good,” says Thompson. “Sabonis was such a factor; he’s 7-2 and he was much older and more experienced than David Robinson. But I felt optimistic we could win. There were no expectations that this was a Dream Team, but Lute had done a remarkable job in getting the most out of almost everyone on the roster.”

After opening an 80-63 lead over Russia with six minutes remaining, everything changed. With 10 seconds to go, Team USA’s lead had been diminished to 87-85 and the Russians had possession and a chance to win at the buzzer. They missed.

Sitting in his apartment in Tucson, Kerr celebrated with his mom and brother as Prince Felipe of Spain was escorted to the court. There, he presented gold medals to Team USA.

Postscript: “The exposure gained for Arizona’s program was such a big step forward,” says Thompson. “People found out what a great coach Lute was. It put the UA program on a national and worldwide stage. It didn’t take long to understand the magnitude of it.

“And, to be truthful, even though Kerr had to redshirt and sit out the 1987 season, it couldn’t have worked out better for him. He returned in 1988, led us to the Final Four and began his almost storybook career in the NBA.”

Then and now photos of Tucson (2020)

Garden Plaza, 1953

Updated

The Garden Plaza office building, 201 N. Stone Ave., Tucson, in December, 1953, shortly after it was completed. Joseph Weiss, a textile businessman from New York City, was "wintering" in Tucson when he decided to buy a used car lot at the site. It was one of the first buildings on Stone Ave. to be constructed after World War II.

Pima County

Updated

The county’s Development Services Department says it was looking for a “smarter way” to set building-permit fees.

All Saints Catholic Church, 1963

Updated

All Saints Catholic Church, 400 S. 6th Ave., Tucson, in 1963.

All Saints Catholic Church, 2020

Updated

Tucson Center for the Performing Arts, 400 S. 6th Ave., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020. it was formerly All Saints Catholic Church.

Corbett's Lumber, 1955

Updated

Corbett's Lumber at 4545 E. Speedway in Tucson in 1955.

Corbett's Lumber, 2020

Updated

Tile With Style, 4545 E. Speedway Blvd., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020. It was formerly Corbett's Lumber.

Coronado Hotel, 1987

Updated

The historic Coronado Hotel at 4th Ave. and 9th St. in Tucson, had seen better days by 1987. The 42-unit hotel, built in 1928, is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. A non-profit group saved the hotel from the wrecking ball in 1989.

Coronado Hotel, 2020

Updated

Coronado Apartments, formerly The Coronado Hotel, 402 E. 9th St., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020.

Hi Corbett Field, 1963

Updated

Hi Corbett Field at Gene C. Reid Park, Tucson, in 1963.

Hi Corbett Field, 2020

Updated

Hi Corbett Field, 700 S. Randolph Way., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 28, 2020.

Perkins Motors, 1955

Updated

Perkins Motors and Texaco gas station at Stone Avenue and Alameda Street, Tucson, in 1955. It was replaced by the Pima Savings building, which opened in 1956.

Perkins Motors, 2020

Updated

The Little One restaurant, 151 N. Stone Ave., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020. It was formerly the site of Perkins Motors.

Roskruge Hotel, 1965

Updated

The Roskruge Hotel at 109 S. Scott, Tucson, in 1965. It was built in 1904 and demolished in 1984.

Roskruge Hotel, 2020

Updated

Empty lot on the north west corner of E Broadway Blvd. and S. Scott Ave., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 28, 2020. It was once the site of the Roskruge Hotel. A high-rise office/retail building is planned for the site.

Selby Motors Mercury, 1956

Updated

The new Selby Motors Mercury dealership at 2200 E. Broadway Road, Tucson, in 1956. The business moved from 820 S. 6th Ave.

Selby Motors Mercury, 2020

Updated

Chevron and Quick Mart on the southeast corner of E. Broadway Blvd. and S. Plumer Ave., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020. It was formerly Selby Motors Mercury.

Temple of Music and Art, 1965

Updated

The Temple of Music and Art, 330 S. Scott Ave., Tucson, in September, 1965. It was built in 1926 and underwent an extensive renovation in 1990.

Temple of Music and Art, 2020

Updated

Temple of Music and Art, home of the Arizona Theatre Company, 330 S Scott Ave., in Tucson, Ariz. on January 23, 2020. The building underwent an extensive restoration in 1990.

Stravenue origin story is a trip down memory lane for one Tucson family

UpdatedWe have left turns from Michigan and potholes from the pits of hell, but one local traffic oddity is an Old Pueblo original.

What do you call a road that runs diagonally between an east-west street and a north-south avenue? Here — and nowhere else in America, apparently — that’s known as a stravenue.

Pima County is home to 40 of them, mostly in mid-century neighborhoods built around Tucson’s angled arteries — Aviation Parkway, Benson Highway, the Union Pacific Railroad tracks and Interstate 10 east of I-19.

The U.S. Postal Service even has an official abbreviation for the stravenue (that would be STRA), though mail carriers outside of Southern Arizona don’t need to concern themselves with it.

“Our records indicate the name is only found in Tucson, Arizona,” said Roy Betts, national spokesman for the Postal Service.

Tracing the origins of a made-up word

So who is responsible for coining the term?

Wikipedia gives credit for the stravenue to “Mr. Tucson” himself, Roy P. Drachman, who reportedly dreamed it up in 1948 as part of Del Webb’s Pueblo Gardens development near 22nd Street and present-day Kino Parkway.

But don’t believe everything you read on the internet. The apparent source for that historical nugget is a reader comment posted beneath an Arizona Daily Star story from 2008, which is pretty thin gravy, even for an online encyclopedia.

Arizona Highways magazine featured Del Webb’s Tucson development, Pueblo Gardens, in the November, 1948 edition.

Recent research by historian and preservationist Demion Clinco points to a more likely candidate: another prominent Tucsonan who played a large role in the city’s post-war development.

Clinco said the earliest appearance of a stravenue he can find is on the plat map for a subdivision called Country Club Park, a wedge-shaped neighborhood hemmed in by Aviation Road, Country Club and 29th Street.

It features six stravenues that were mapped out in February 1948, three months before the plat for Pueblo Gardens.

The same land surveyor produced both maps: Tony A. Blanton from the Tucson architectural firm of Blanton and Cole.

In December 1948, Blanton submitted another plat map, this time for North Campbell Estates at Campbell and Glenn, and again there were stravenues.

Planner and land surveyor Tony Blanton, ca. 1940s.

“Based on this, I think it would be fair to say Blanton brought us the stravenue,” Clinco said. “If he did not actually invent the term, he produced the first one and promoted their popularity in the late 1940s.”

Blanton helped put Tucson on the map

Longtime Tucson land surveyor Don Rockliffe said details like road names are often handled by the planner who is hired to draw up the subdivision map.

“Unless the developer had some pet names in mind, he left it up to the engineering firm to come up with the street names,” he said.

Of course, Rockliffe might be a little biased. Tony Blanton was his grandfather.

Rockliffe said his father, Donald Alan Rockliffe, married Blanton’s eldest daughter, Beverly, and worked as draftsman and design engineer for his father-in-law.

Tony Blanton, a prominent Tucson planner for decades, is a likely candidate for being the person who originated the term “stravenue.”

Blanton and Cole was one of Tucson’s first engineering and architectural companies, Rockliffe said, and it soon became the preeminent firm of its kind in the city.

By 1958, it had 42 employees and a newly built downtown office at Main Avenue and Pennington Street, though that building was lost to urban renewal about a decade later. “Now it’s buried beneath the county courthouse,” Rockliffe said.

Major local clients included the University of Arizona, several public school districts, Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Hughes Aircraft Company. Blanton and Cole also worked on projects across Arizona and in eight other states.

Arizona Highways magazine featured Del Webb’s Tucson development, Pueblo Gardens, in the November 1948 edition. One “stravenue” origin story is that Roy P. Drachman reportedly dreamed it up in 1948 as part of Pueblo Gardens

.

From cowboy roots to the city’s “in-crowd”

Rockliffe said his grandfather was “part of the ‘in-crowd’ in Tucson, I guess you’d say, but he started out humble.”

He was born George Anthony Blanton in Calgary, Alberta, in 1910. His cowboy father was originally from Southern Arizona, and the family moved back here in 1911 — first to Willcox and then to Tucson in 1914.

After graduating from Tucson High School and studying at the UA, Blanton got his first engineering job with the Southern Pacific Railroad. He later worked for the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, the U.S. Bureau of Public Roads, Pima County and the city of Tucson before launching a private practice with Frederick P. Cole, a former draftsman for the county.

Somewhere along the way, Blanton changed his legal signature to Tony A. Blanton — short (and somewhat redundant) for Tony Anthony Blanton.

Since learning of his family’s possible connection to Tucson road-naming lore, Rockliffe has done some research of his own that bolsters Clinco’s case.

He said there are 10 Tucson subdivisions that include stravenues, all of them mapped between 1948 and 1960. Blanton and Cole was the surveyor for six of them, including the five oldest.

Surveying streets runs in the family

The city planning and zoning commission added the made-up word to Tucson’s official street naming and numbering system in November 1948.

In May 1949, the Tucson Daily Citizen ran a piece explaining the new street type, which it described as “gobbledygood (sic) for diagonal.”

Tony Blanton rides a horse with his first child, Beverly, at his father’s ranch house on Hedrick Drive, near Campbell Avenue and Fort Lowell Road in 1936.

“I can remember seeing Cherrybell Stravenue as a child and thinking that was all so strange,” said Rockliffe, who retired in 2019 after 39 years as a land surveyor for Tucson Electric Power.

He never dreamed at the time that he might be related to the man who invented them — the man for whom Blanton Drive near Fort Lowell Road and Tucson Boulevard is now named.

Rockliffe said he used to visit his grandfather on Sundays and holidays. Occasionally, he would join him in his box seats at Hi Corbett Field for Cleveland Indians spring training games.

Blanton died in 1969 at the age of 59.

Rockliffe was about 11 at the time. Not long after, he began to learn the family business from his own father. He used to watch him work at his drafting table, and he later helped him draw a few subdivision plats before enrolling at the UA to become a registered professional land surveyor himself.

“He taught me surveying,” Rockliffe said of his dad, the likely son of the stravenue. “It felt like it was kind of in the blood.”