Editor’s note: Over five weeks, Star columnist Greg Hansen will profile 10 times that Tucson teams beat No. 1. Today: Arizona’s 13-10 win over top-ranked USC in 1981.

In the space of three Arizona football seasons, Jeff Kiewel played for Wildcat teams that beat No. 1 USC, No. 2 UCLA, No. 6 ASU and No. 8 Notre Dame. Upsets? Shockers? Flukes? Kiewel came to know the difference.

“If you watch the film of our victory over USC, you know we didn’t get lucky,” he says now, 39 years later. “We could play with anybody.”

But nobody expected it.

On Oct. 10, 1981, Arizona arrived at the Los Angeles Coliseum about 11 a.m. UA coach Larry Smith was so agitated that he had difficulty killing two hours until kickoff.

A Star photographer, allowed in the UA’s pregame locker room, took photographs of Smith, alone, sitting in a corner, staring into space.

Let’s just say Smith didn’t smile for the camera.

The Trojans, ranked No. 1, were two weeks removed from a rousing victory over No. 2 Oklahoma. They were bracing for a showdown against Notre Dame two weeks later, a game some projected would produce a national champion. That year’s Heisman Trophy winner, Marcus Allen, trotted onto the field with his USC teammates. He would gain 211 yards.

It was no place for the timid.

“I have such strong memories of that game that I still remember the smell of the grass,” says linebacker Ricky Hunley, who would go on to be inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame.

“There had been a Rolling Stones concert at the Coliseum the night before and the field had been covered by a tarp. It was just awful, filthy. The last thing you wanted was for some Trojan to knock you on your ass and rub your face in the dirt.”

As it turned out, the 21-point underdogs from Tucson rubbed USC’s noses in the dirt, winning 13-10.

“In my days at Arizona, we were true Giant Killers,” says Kiewel, a Sabino High grad who went on to start for the Atlanta Falcons. “But we also had some notable slip-ups, losing to Fresno State and a bad (1-8-1) Oregon team. The bigger the game, the better we were.”

USC was the biggest name in college football in 1981. It was the first time in history Arizona had played a No. 1-ranked team. Nobody saw it coming — except maybe Kiewel and Hunley and the core of an Arizona team that had rallied to beat John Elway’s Stanford team 17-13 a week earlier.

It started not with promise, but with a kick to the gut.

Allen bolted 74 yards for a touchdown on the first drive of the game. Arizona fumbled the ensuing kickoff.

USC kicked a field goal. It was 10-0 before Arizona knew what hit it.

After the game, when the tears had been wiped from his cheeks, Smith had no true explanation for surviving USC’s explosive start.

“Maybe they thought it was going to be easy,” he told me at the Los Angeles airport late that afternoon. “They might’ve been lulled to sleep.”

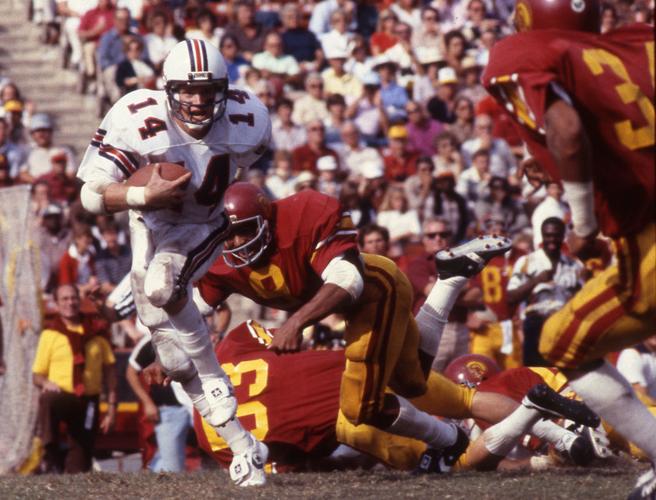

Arizona receiver Brad Anderson catches a 31-yard pass from Tom Tunnicliffe as Arizona upset USC in Los Angeles on Oct. 10, 1981.

The Trojans didn’t score again. The national audience watching on CBS saw an Arizona defense led by Hunley and linemen Gary Shaw, Ivan Lesnik and Julius Holt control the line of scrimmage. USC didn’t cross Arizona’s 42-yard line the final 52 minutes of the game.

Arizona outgained USC 402 to 297; the Trojans entered the game ranked No. 2 in the nation with 483 yards per game.

How did that happen?

It was offensive coordinator Steve Axman’s ball-control game plan: kill the clock, keep Allen off the field, don’t get sacked, don’t fumble the ball.

The deciding possession began innocently in the middle of the third quarter, with USC leading 10-6. Here’s the script of how Arizona chopped down the mighty Trojans in what some consider the most meaningful possession in more than 100 years of UA football:

First down at the UA’s 41:

• Incomplete pass

• Dearl Nelson, 6-yard run

• Mark Keel, 12-yard reception

• Bill Redman, 9-yard run

• Brian Holland, no gain

• Chris Brewer, 3-yard run

• Tom Tunnicliffe sacked, minus-12 yards

• Brad Anderson, 25-yard reception

• Brewer, 2-yard run

• Vance Johnson, 13-yard TD reception

Some of those plays were memorable. Keel’s 12-yard catch was a fully-extended, one-hand grab. Anderson, a future Chicago Bears receiver, got open on a second-and-22 pass. And Johnson’s TD catch was more of a run; he sprinted the final 11 yards to the end zone with 0:02 remaining in the third period.

In its 1981 victory over USC, Arizona outgained the Trojans 402 to 297. USC took a 10-0 lead but didn’t cross Arizona’s 42-yard line over the final 52 minutes of the game.

Johnson, a freshman from Cholla High School and future Super Bowl receiver for the Denver Broncos, wasn’t even aware his score had given Arizona the lead. He thought the game was tied.

In the locker room after the game, I asked Johnson if scoring the winning touchdown redeemed his first-half fumble that led to a USC field goal.

“Winning touchdown?” he said. “What do you mean?”

I just stood there, shaking my head, half suspecting Johnson was kidding around.

“It was a tie,” he said, unconvincingly.

He looked around the joyful locker room and said “What … well I guess that gets me off the hook. I was afraid the coaches would bench me.”

Hunley, who later was Johnson’s teammate with the Denver Broncos, remembers Vance’s confusion.

“As a freshman, Vance sometimes ran scared,” says Hunley. “But in that game, on that touchdown pass, it was like he was shot out of a cannon. USC had some players you couldn’t run by, but Vance ran by them.”

There was no scoring in the fourth quarter. Not even a threat of a score. Arizona’s offensive line controlled the game against a USC team that finished 9-3 and ranked No. 14.

Arizona receiver Brad Anderson catches a 31-yard pass from Tom Tunnicliffe as Arizona upset USC in Los Angeles on Oct. 10, 1981.

“We had such a good, smart offensive line: Frank Kalil, Glen McCormick, Marsharne Graves ... a bunch of guys that knew the game plan and executed it,” says Kiewel. “If USC thought it was going to be an easy day they soon found it was going to be a dogfight. We had an air of confidence. Something like ‘this is our time.’ ”

And so it was.

As the Wildcats celebrated in their locker room at the Coliseum, a strange thing happened. USC coach John Robinson entered, alone, and almost every head turned to look at the man who had coached USC to the 1978 national championship.

“It was rowdy in our locker room, but Robinson went from player to player shaking their hands, congratulating each one of us,” Kiewel said.

“I still remember him telling me, ‘You should be proud of yourself; you outplayed us in every way.’ It’s the classiest move I had ever seen to that point in my life.”

Arizona finished the season 6-5 and unranked. A year later, the Wildcats beat No. 9 Notre Dame and No. 6 Arizona State in much the same style — toughness and ball control — they used to beat USC.

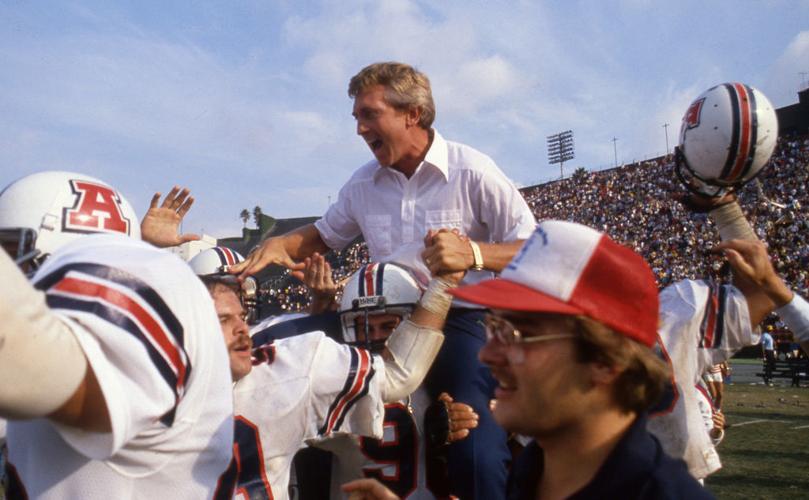

Arizona coach Larry Smith gives a hug to AD Dave Strack after Arizona upset USC in Los Angeles on Oct. 10, 1981.

Postscript: Smith, who went on to coach at USC from 1986-92, told reporters “it’s greater, better and sweeter than any victory I’ve ever been part of.”

When the Wildcats arrived at the Tucson airport about 7:45 p.m., an estimated 1,500 fans mobbed them at the gate.

Where are they now? Kiewel, who played for the Atlanta Falcons, earned an MBA at Duke and has worked mostly as a national sales representative for several firms. He is now an executive in a national interior furniture firm and lives in Tucson. He is an assistant coach at Tanque Verde High School.

McCormick is a United States attorney living in Phoenix.

Tunnicliffe owns a real estate firm in Burbank, California.

Two UA starters in the game have died: wide receiver Kevin Ward, who went on to play baseball for the San Diego Padres, died in 2018. Gary Gibson, a starting outside linebacker, died in 2019.

Hunley, who went on to play seven years in the NFL, coached for the Washington Redskins, Cincinnati Bengals, Florida Gators, Oakland Raiders and at USC, Missouri and Memphis. He works for an outdoor billboard firm in Los Angeles.

Smith returned to Tucson after he coached at Missouri from 1994-2000. He died of leukemia in 2008.