The man who owns Cooke Land and Cattle Company, the man who spent six months with the Denver Broncos, two decades as pro rodeo steer wrestler and might have been the best high school football player in Tucson in 1979, remembers an August afternoon at McKale Center when Lute Olson introduced the team’s late-arriving point guard, Steve Kerr.

Yes, Troy Cooke played basketball for Lute Olson, too.

“Steve showed up late that year because he had been in Lebanon with his dad,” Cooke, now 58 and living in Show Low, says. “I looked and him and thought ‘who’s this guy, the water boy?’

“He wasn’t real athletic. He didn’t look like a basketball player. My perception couldn’t have been more wrong. But by the end of that season (1983-84), I could see how he played to his strengths — he was very smart and very talented — and he excelled at Lute’s system. Plus, he was a great guy. Everybody liked him.”

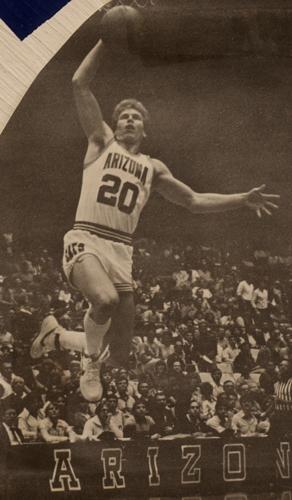

Troy Cooke

Five years ago, when Cooke resigned as the basketball coach at Show Low High School — his teams won 42 games his last two seasons — he applied for several small-college coaching jobs. Guess who mailed him a hand-written letter of reference?

Steve Kerr.

“Steve wrote that he always looked up to me,” Cooke remembers. “It was very special.”

Former UA basketball player Troy Cooke as a senior, who played for Lute Olson’s first Arizona team from 1983-1984.

Kerr wasn’t the only person who looked up to Cooke, a 6-foot-4-inch, 215-pound shooting guard and wide receiver from Flowing Wells High School whose athletic career is one of the most compelling in Southern Arizona history.

He grew up in small-town Bowie, 105 miles east of Tucson near Interstate 10. His father, Tom, a farmer who also worked at the old Union Carbide mine, had been a minor-league baseball player, a Golden Gloves boxer and a junior-college football star whose sons followed his lead; two of them played college football and Troy college basketball.

By the time he was 14, Troy was so advanced for the small-school athletic program in Bowie that he moved to Tucson, bunking at his sister’s house, and became not just a first-team All-City basketball player but first-team All-City football, too.

Cooke enrolled at El Camino College in California, and soon drew a scholarship offer from Jerry Tarkanian at UNLV. He could’ve played at Mississippi State, Boise State, Weber State and even Oregon State, then the nation’s No. 1 ranked basketball program. He ultimately chose to be part of Ben Lindsey’s brief, ill-fated 4-24 season at Arizona.

But rather than look back on Lindsey’s missteps, Cooke chooses to speak about how Olson transformed UA basketball almost overnight.

Troy Cooke, who played for Lute Olson’s first Arizona team, owns a land and cattle company and coaches at Western New Mexico.

“You could feel it from the first day — we were going to be successful,” Cooke says. “He was just different. Everything was first-class. He was so organized. Our scouting reports were so thorough and spot-on. We started comporting ourselves with class. I was a senior, and always wished I’d had another year or two to play for him.”

In Olson’s first game at Arizona — Nov. 23, 1983 against NAU — Cooke was the sixth man. Kerr was his backup. Cooke started four games and averaged 11 minutes per game, but was talented enough to play professionally in Belgium, Malta and Scotland, and in the old CBA.

“It’s funny how UA basketball was only two years of my life, but it’s an identity that is part of the rest of your life,” says Cooke. “The success they’ve had carries over. Even all these years later when I tell someone I played at Arizona, they’ll perk up and say, ‘You played for Lute Olson?’ ”

After his professional basketball career, Cooke had saved enough money to buy a fitness center, the Peoria Athletic Club near Phoenix. He dedicated himself to fitness the way he had as a schoolboy athlete to football and basketball, and gained about 25 pounds of muscle. Though some contacts, the Dallas Cowboys and Denver Broncos expressed interest.

A Broncos scout flew to Phoenix, put Cooke through several days of mini-camp-type workouts and, at 27, Cooke signed a two-year, make-good contract as a tight end with Denver. He went from shooting baskets with Steve Kerr to catching John Elway’s passes.

“After about six months, (coach) Dan Reeves called me in and said, ‘If you were 22 instead of 27, we’d keep you,’” says Cooke. “But, hey, I had my shot. I felt like George Plimpton. We sold our fitness club and bought a cattle ranch in Alpine. Farming and ranching has been my blood from the time I grew up in Bowie. I just loved it.”

Every year for a decade or two, Cooke spent time on the pro rodeo circuit in the Southwest, wrestling steers, roping calves. He competed in Tucson’s La Fiesta de los Vaqueros more than a dozen times.

That’s George Plimpton and then some.

For the past five years, Cooke has been an assistant basketball coach at Western New Mexico in Silver City, an NCAA Division II school that played last season against Arizona at McKale Center. Somehow, commuting from Show Low to Silver City, Cooke made it work. As recently as last month, Cooke was one of two finalists for a small-college head coaching position in Southern California.

“Coaching is part of me; maybe not high school coaching any more — the parents and the politics can wear you out — but I’d like to be a college head coach,” he said. “I thought a lot about being Lute’s graduate assistant when I left Tucson, but it’s probably good I didn’t. I’d have been hired and fired and hired and fired several times and retired by now. I feel fresh now. I feel like a 30-year-old coach.”

Cooke’s ties to his alma mater will be refreshed this year. His oldest son, Canyon, will enroll at Arizona this month. He’s a 4.0 student with an academic scholarship who plans to major in biomedical engineering.

In the meantime, Troy Cooke will continue to work his cattle ranch, stay involved in coaching and help his wife Elaine, also a UA grad, raise their three children.

“I’ve always wanted to be sure that when I got old I wouldn’t be sitting on a park bench, regretting what I did with my life,” he says. “I wanted to make sure I tried everything. “

He didn’t leave a box unchecked.