It’s 3:30 a.m. in foggy Fayetteville three days before Christmas, 1991. I am sleeping in a motel near the University of Arkansas when the phone rings. I roll over. The phone continues to ring.

“Yes?”

“All the flights today are canceled,” Bruce Larson says. “We’re driving to the Tulsa airport in 15 minutes. I made a reservation for you.”

“Seriously?”

“I’ll knock on your door in 15 minutes.”

Fifteen minutes later, Larson is at my door.

“Hurry,” he says. “It’s going to be tight. I don’t think you want to be stuck here on the weekend before Christmas.”

Still half-asleep, I get in the back seat. The former Arizona basketball coach rides shotgun to Dave Sitton, who is Larson’s TV broadcast partner. I thank them for thinking of me; getting stranded in Arkansas the day after No. 2 Arizona lost to the No. 19 Razorbacks is no one’s idea of a holiday getaway.

I had flown into Fayetteville with my Star colleague Jon Wilner, but he is driving to nearby Fort Smith, rebooking a flight to his hometown near Washington D.C. I was alone. Somehow, Larson figured it out. Who would do that for you at 3 in the morning?

The drive to Tulsa on Highway 412 is perilous. Visibility can’t be more than 50 yards. Larson and sink into our seats, afraid to look as Sitton maneuvers through the fog. Our flight leaves for Dallas at 6:30. Catch it or spend the day in Dallas, or longer.

As we near the airport, tension increases. Sitton pulls over in front of the terminal to let us off. He’s still got to return the rental car and catch a shuttle bus. He’ll never make it. Larson nudges him on the shoulder and tells Dave to get out.

“You’ve both got young kids at home,” he says. “I’ll return the car. You guys get on that plane.” Sitton balks but Larson stands firm. “Hurry,” he says.

Sitton and I sprint to the gate and make the flight just as the door closes. Bruce Larson, coach, professor, TV analyst, husband, father of five and superstar human being, misses the flight. He spends the day and night in Dallas, arriving home Monday afternoon.

What kind of a man does that for you? A very good man. • • •

Sunday afternoon, Larson fell at the Tucson home of his son, Brian. The UA’s head basketball coach from 1961-72 broke his pelvis and became seriously ill. Even though he had been an active racquetball player and golfer through his late 80s, Larson lingered near death.

In a bit of serendipity, Larson’s 1965 All-WAC guard, Warren Rustand, began thinking of his coach Monday morning. The impression was so strong that Rustand drove to Larson’s house.

“He was being cared for by his daughters, Brenda and Becky, along with three of his grandchildren,” says Rustand, a lifelong entrepreneur and author who is CEO of Smith Capital Consulting, LLC. “I had a delightful conversation with him as we recalled old tales of his career.”

Larson had been reading part of Rustand’s new book, “The Leader Within Us,” in which the coach’s influence on Rustand’s career and others is referenced.

This is part of the email Rustand later sent to his former Wildcat teammates:

“I had the chance to be his assistant coach for nearly three years, so I got to know another side of him. I would make these observations: He was one of the best and finest men I have ever known. He lived a good life with his family at the center of all he has ever done. He was completely consistent in his core values and the worth he saw in each person’s life.

“He was always positive and upbeat. I never heard him say a negative thing about another person. From the time I met him as a high school senior to Monday’s conversation he was always the same man, the same person. He reveled in other people’s success and cheered for the underdog. He quietly supported scores of athletes and individuals who needed help, all without acknowledgment or recognition.

“Perhaps, just perhaps, we honor him by being more like him in every way.”

Larson died at home Tuesday evening. He was 94.

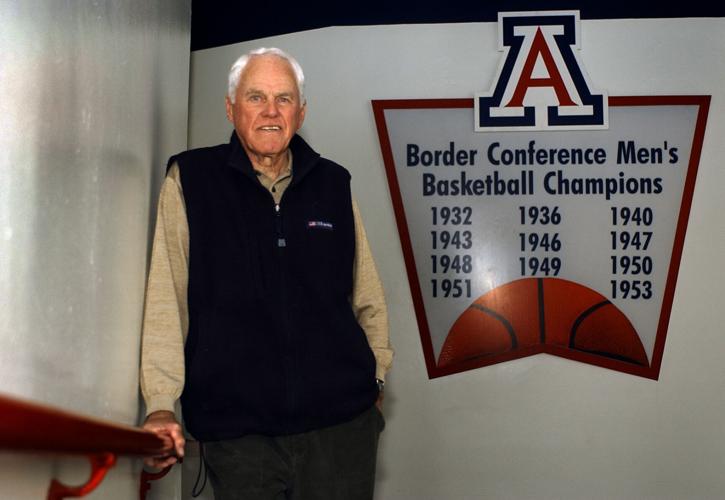

Bruce Larson coached the UA men’s basketball team from 1961-72, then stayed on campus as a professor until 2002.

• • •

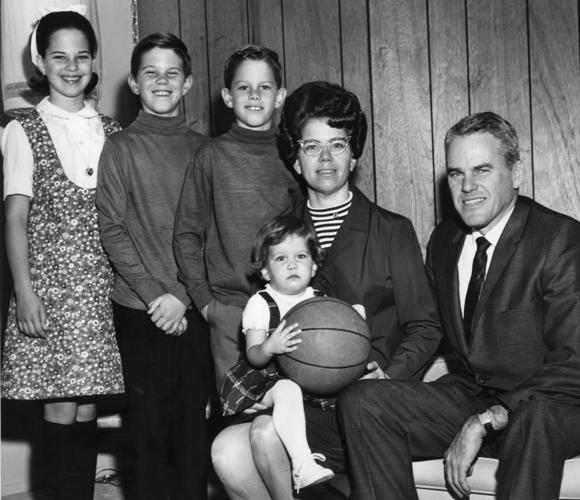

Larson grew up in Fargo, North Dakota, and enlisted in the Navy in World War II. While stationed in California, he was introduced to his unit commander, the father of UA basketball standout Linc Richmond. An athlete of note, Larson used the GI Bill to enroll at the UA, where he became Richmond’s teammate.

He ultimately became the head coach and athletic director at Eastern Arizona College, and from there coached Weber State to the 1959 NJCAA basketball championship. That’s when Fred Enke, his UA basketball coach, persuaded him to return to his alma mater and become Enke’s successor.

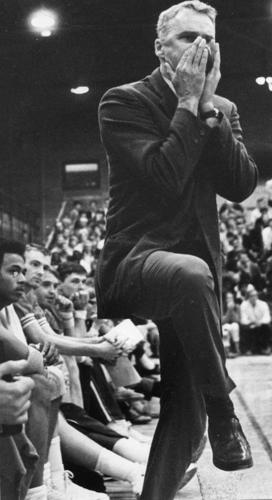

When Enke became bed-ridden after kidney surgery, seriously ill with a staph infection, Larson took command of the 1960-61 Wildcats. In February, 1961, Enke announced he would retire and that Larson would take charge.

With Larson leading a climb from the Border Conference to the WAC, plans to build a grand arena with 10,000 seats were hatched; the Wildcats would finally move out of antiquated Bear Down Gym. But politics ensued; funding was slow to be granted. By the time McKale Center was complete, in February 1973, WAC rivals Utah, BYU, Colorado State, UTEP and New Mexico had built new facilities.

Arizona’s recruiting suffered; the Wildcats were left in the dust.

The UA went 136-148 in Larson’s 11 seasons. A year before McKale was to open, giving the Wildcats an unprecedented recruiting platform, new UA athletic director Dave Strack asked Larson to resign.

The school held a season-ending banquet and presented Larson with a watch and a TV set. He gave an emotional speech, saying how much he loved his time coaching Arizona’s basketball team.

Larson was only 45, entering the prime of a coaching career. Rather than publicly complain, he chose to remain on the UA faculty, teaching in the Physical Education department until 2002. He was the analyst for UA basketball broadcasts from 1985-99.

Over the years, I often engaged Larson in conversation about the timing of his coaching career and the UA’s delay in building McKale Center and the seeming unfairness of his discharge.

“Those are the cards I was dealt,” he would say. “I did the best I could. It all worked out in the end.”

He told me that in 1968, just as Weber State became a Division I basketball program and planned to build a 10,000-seat basketball arena, he had been offered a chance to be his old school’s athletic director.

“I was tempted,” he said. “But Tucson had become our home. It wouldn’t have been fair to move my wife and our kids.”

As always, Larson thought about others before he thought about himself.

On Thursday afternoon I walked through the corridors of McKale Center for the first time in a year. I could find no reminder of Bruce Larson’s career at his alma mater. No framed photograph. No plaque on the wall. None of the many locker rooms and coaching offices named in his honor.

Nothing from which to remember how he set a template for integrity, as well as plotting the direction and foundation to build McKale Center.

Bruce Larson would’ve been the last person to request such an honor — but among the first to deserve it.