On Sunday’s drive to McKale Center, I continued a few blocks south on Campbell Avenue and stopped at 1836 E. Ninth St. That’s where Marvin Borodkin grew up, became a Tucson High School state tennis champion, captain of Arizona’s first-ever NIT basketball team and a bomber pilot in World War II.

It had nothing and everything to do with Arizona’s 90-69 victory over Illinois.

I sat in my car for 10 minutes, imagining a young Borodkin walking to Bear Down Gym, jacked up to play Arizona State, or even the San Diego Marines and the Albuquerque Air Force Base Flying Kellys, as the Wildcats did in 1942-43.

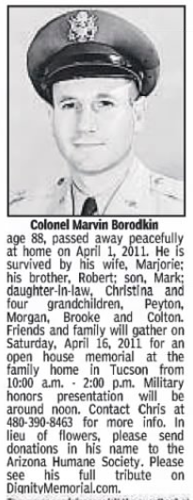

In 1943, Veterans Day was known as Armistice Day. The name changed in 1954, after Borodkin had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and would ultimately be promoted to colonel and go on to serve in Vietnam and as a military attaché to Yugoslavia.

Borodkin’s name isn’t in the Ring of Honor at McKale Center, but on Veterans Day 2019, I’m not sure there’s ever been a more honorable Wildcat basketball player than Marvin Borodkin.

Borodkin was a B-25 pilot who missed Arizona’s 1944 and 1945 basketball seasons, flying more than 200 hours of combat duty, mostly over Japan and China.

When he returned to Tucson and rejoined the UA basketball team, he endured a lingering back injury suffered during World War II, sometimes missing practices, but never a game.

Borodkin was a gamer, one of the true winners across the last 75 years of Arizona basketball. I’d like to think that as his alma mater defeated Illinois on Sunday night, he is remembered not just for being a cornerstone of the UA’s basketball program, but also as a reminder that you don’t need to be a first-round draft pick to make a difference.

Do you know Borodkin is the UA’s all-time leading free-throw shooter? He shot a ridiculously good 88-for-91 from the foul line, or 97%. That far eclipses Steve Kerr’s 82% free-throw percentage, and Kerr has forever been known as the Wildcat you’d most like to see at the foul line in a close game.

Borodkin wore jersey No. 12, later awarded to such high-profile Wildcats as Bob Honea, Matt Othick and Josh Pastner. No one wore it with more meaning than Borodkin, the son of a New York Philharmonic percussionist who moved to Tucson in the 1930s, as many of that era, for the dry climate and a more healthy place to live and breathe.

On Veterans Day, it seems appropriate to remember Borodkin’s place in the history of Tucson’s most cherished game, college basketball. Borodkin was one of those who helped forge Tucson’s identity as a basketball town, a starter on the 1946 club that was invited to the NIT — then the nation’s most prestigious college basketball event — a 25-5 team that set the foundation for the 21-3, 26-5 and 24-6 teams to follow.

He was a graduate assistant coach for Fred Enke, earning a law degree at the UA, while sellout crowds filled Bear Down Gym as Arizona enjoyed its first taste of national basketball success.

Borodkin is among those who helped make it possible for Arizona to put McDonald’s All-Americans Nico Mannnion and Josh Green on the court, to build McKale Center, and to fill the arena on a Sunday night in 2019, beating Illinois of the Big Ten Conference, which would’ve been unthinkable when Lt. Marvin Borodkin returned from World War II in 1946 and regained his spot in Arizona’s lineup.

As I parked in front of Borodkin’s old home on East Ninth Street, I thought about Veterans Day. I thought about how much college basketball has changed since World War II and what type of legacy Borodkin and his Wildcat teammates — boys before the war — left for today’s Wildcats and UA fans.

The one time I had the privilege of talking to Borodkin, he told me that he never dunked a basketball.

“Our coach, Fred Enke, wouldn’t allow us to dunk,” he said with a smile. “But I couldn’t jump that high anyway.”

He lived long enough to see Arizona become a national champion, sit in McKale Center and absorb how much the game had changed since the winter of 1942-43.

Before he died in 2011, Borodkin’s perspective on modern college basketball was that of a man who grew up in a more simple time, a man whose roommate on UA road trips was Mo Udall (who ran for the presidency of the United States), a man who was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, which he treasured far more than becoming an All-Border Conference ballplayer.

“College basketball is a business now,” he told the Star after the Wildcats reached the 1994 Final Four. “Whether that’s for the best is questionable.”

He never played in the McDonald’s All-American Game and never dreamed of playing in the NBA. But he did dream of opening a law firm in his hometown, which he did — Borodkin and Lesher. And he became president of the Pima Air and Space Museum.

Not bad for a guy who couldn’t dunk.

On the day I talked to Borodkin, he told me he was unable to finish Arizona’s 22-2 season of 1942-43.

“I was called to duty by the Army Air Corps midway through the season,’’ he said. “It turned out to be one of the best days of my life.”

That’s what I thought of while sitting in my car at 1836 E. Ninth St.

Marvin Borodkin and Veterans Day. For one night, a rousing Arizona victory at McKale Center didn’t seem quite as important.