True story: On Dec. 3, 1983, the Arizona Icecats drew 5,597 fans for a game against a collection of USC students whose uniforms didn’t match.

Twenty-four hours earlier, the college kids drew 5,359. It was club hockey. There were no standings and no real value to the games, yet they drew 10,956 fans to Tucson Convention Center.

Hockey was, for a year or two, a ticket more valued than one to watch basketball games at McKale Center. But then, over the years, hockey interest in Tucson waned until it became something of a latter-day Huey Lewis song.

They say the heart of Tucson hockey is still beating;

And from what I’ve seen lately I believe ’em;

For a long time, the old boy was barely breathing;

But the heart of Tucson hockey, the heart of Tucson hockey, is still beating.

Somehow, in what seems like the last 45 minutes, Tucson Mayor Jonathan Rothschild, his high command and the once-bungling Rio Nuevo project, completed the most dazzling piece of sports enterprise in Tucson since the Cleveland Indians arrived for spring training in 1947.

This ain’t “let’s build them a ballpark down on Ajo.”

It’s not Martin Stone or Jay Zucker or some heavily invested CEO looking to make a profit at Tucson’s expense, selling when the market is right.

“You can’t look back,” Rothschild said Thursday, sitting on a dais next to some unfamiliar men in suits and ties from Phoenix, the type of thing that usually generates serious loathing from Tucsonans.

But this time the risk is all on the suits and ties from Phoenix. The bills are being paid by a full-blown member of the National Hockey League, not by some independent owner looking to turn a buck.

Tucson’s long sports losing streak, from the demise of the Copper Bowl to the death of the Sidewinders to the loss of the PGA Tour, has ended.

By this time next May, the Tucson Stick Lizards (that’s my official name-the-team proposal) of the American Hockey League will have played 38 games at the dressed-up TCC, which will be further improved by another makeover, about $3.5 million in touch ups, paid for by the Rio Nuevo project.

The would-be Stick Lizards (also the name of a 1932 Tucson minor-league baseball team) will play against teams named Reign, Barracuda, Condors and Gulls, maybe even the Lake Erie Monsters, if Tucson’s first year in the AHL results in a trip to the Calder Cup playoffs.

My Lord, can you imagine the demand for tickets if the Stick Lizards are involved in the Calder Cup? That sounds so dignified.

The San Diego Gulls, in their first season as an AHL franchise, recently drew 30,779 for four Calder Cup games. And that’s in San Diego, where you can watch the Padres, go to the beach, or to the Gaslamp Quarter or a million other things for entertainment.

Unlike baseball, this is one time Tucson and Phoenix were meant to be together.

It’s not a complicated partnership. Arizona Coyotes owner Anthony LeBlanc is a Canadian (naturally) who knew that Florida businessman Charlie Pompea was having difficulty paying the bills for the AHL’s Springfield (Massachusetts) Falcons.

He offered to buy the team from Pompea, who rescued the Springfield team from financial troubles in 2009. The Falcons averaged a bare 3,114 this season, and without NHL funding, were doomed. Pompea talked to 28 groups about buying the team, but LeBlanc and the Coyotes had the most motivation and probably the most money.

The AHL opened NHL-affiliated franchises in five California cities last year, and it made geographical sense for the Coyotes to put a team in Tucson to round out the western division. Imagine how much the Coyotes will save in travel expenses and convenience. It’s 2,613 miles from Phoenix to Springfield.

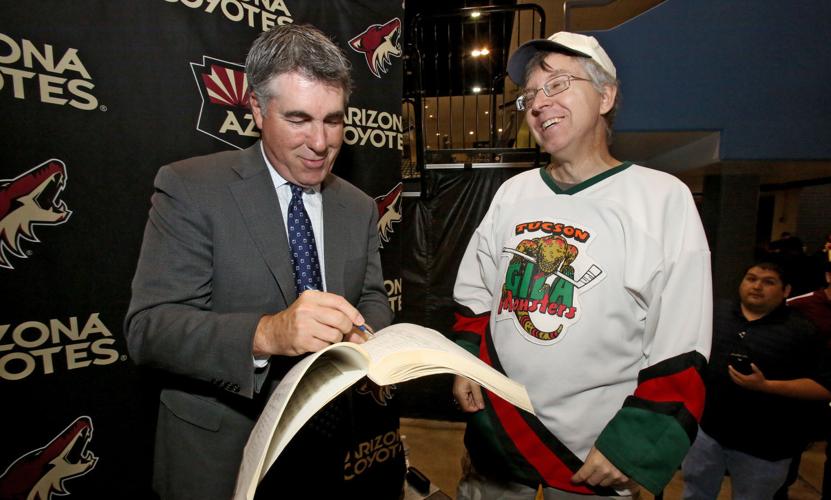

LeBlanc said he thinks the Tucson-Coyotes merger “will thrive” and that Tucson never slipped from the No. 1 spot as a potential site. Coyotes general manager John Chayka said “this is nothing short of a game-changer for our organization.”

What else would they say?

If Tucsonans are skeptical, it’s understandable. But when Rothschild said “the city’s interests are (contractually) protected,” it’s tempting to wish he could’ve been part of the government’s 1990s negotiating team when the Diamondbacks and White Sox were ceded too much power at the Great White Elephant, Kino Stadium.

LeBlanc, who made his fortune as an executive at BlackBerry, among other millennial projects, first considered the idea of moving the club’s affiliate to Tucson in 2013. He didn’t fully vet the possibility of buying the Springfield Falcons and moving them to Tucson until this spring.

It came together with unexpected speed, a credit to both parties, and a reflection on how much each one knew it could benefit from a relationship.

“It was pretty easy,” said LeBlanc. “It’s two hours away and a million people.”

Can the Calder Cup be far behind?