Tucson mayor H.O. Jaastad, the American Legion Drum and Bugle Corps and about 1,000 Tucsonans waited at the Southern Pacific Railroad depot in the early evening of Oct. 3, 1939, awaiting 19-year-old Joe Batiste’s return from a two-month tour of Europe with Team USA’s track team.

Dozens of cars, all adorned with the colors of Tucson High School, lined up for a parade through downtown Tucson.

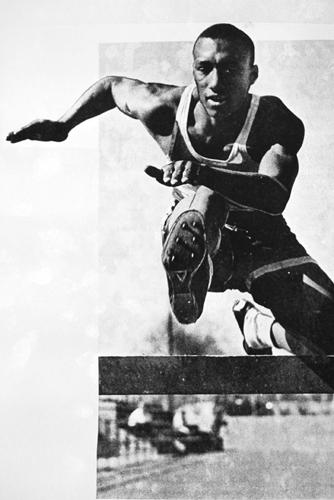

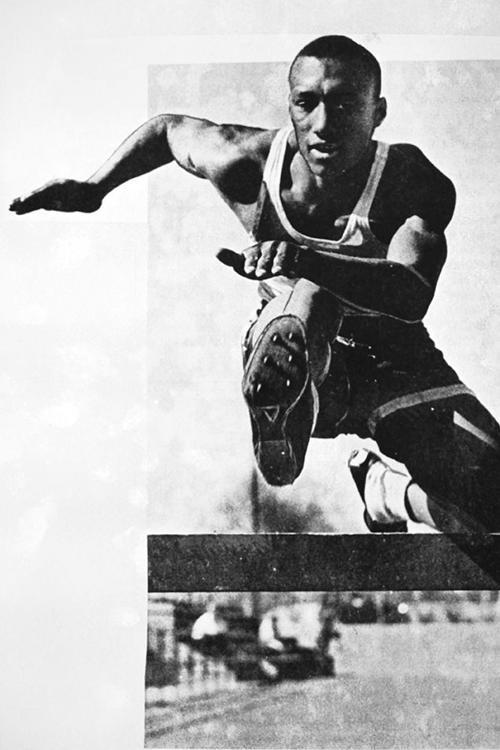

At the time, 1939, there was not a Black athlete on any of the UA athletic teams. The city’s grade schools and middle schools were segregated. Batiste, then a senior at THS, would not be offered a scholarship by the UA even though he had tied the American and Olympic record in the 120-yard hurdles on — of all days — July 4, 1939.

Batiste, a teenager from an impoverished family of six young children, was the first Black person in Tucson to receive such acclaim and attention.

After returning from European track meets in Switzerland, Sweden, England and France, Batiste was declared ineligible to compete for the 1939 Tucson High football team. The Arizona Interscholastics Association ruled that Batiste would have needed to enroll at THS 15 days before classes began.

No exception was made, even though Batiste’s return to Tucson from England was delayed 34 days because Germany invaded Poland, which limited passenger ships across the Atlantic Ocean.

Sadly, that October evening in Tucson was the height of Batiste’s career, if not his life.

Batiste, No. 23 on our list of Tucson’s Top 100 Sports Figures of the last 100 years, ultimately enrolled at Sacramento City College, where he became an Olympic-level decathlete, winning the 1941 and 1942 NJCAA championships. He subsequently enlisted in the Army, becoming a technical sergeant at the U.S. Army Airfield in Marfa, Texas, an administrative assistant for would-be pilots.

After his honorable military discharge, Batiste was accepted at ASU, but he had gained weight and was no longer an elite-level athlete. He played sparingly for the Sun Devils football team but was dropped from the team after the 1948 season.

Batiste struggled with substance abuse. He was arrested numerous times, including once by the FBI for alleged theft of narcotics at the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base. In 1958, suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, he died at the Veteran’s Hospital in Sawtelle, California. He was only 38.

A few weeks before the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, the phone buzzed at my desk. A receptionist at the Star said that a man named L.D. Weldon was in the lobby and would like to speak to me.

I had never heard of L.D. Weldon, but our conversation became something I will never forget.

Weldon introduced himself as the former coach of 1976 Olympic decathlete Bruce Jenner, the man who introduced Jenner to the decathlon and coached him to a gold medal in Montreal.

But Weldon didn’t want to talk about Jenner; he wanted to talk about Joe Batiste.

“I was Joe’s coach at Sacramento City College,” said Weldon, who had earned a master’s degree at the UA and was a former track coach at Amphitheater High School. “If World War II hadn’t come along, Joe would’ve been right up there with the greatest decathletes — Bob Mathias, Bill Toomey, Bruce Jenner.”

Although it was no help to his personal life, Batiste was named an honorary member of the American 1940 and 1944 Olympic teams, even though the Olympic Games were canceled those years.

Upon learning Batiste was dying of liver disease, Weldon went to the old Pima County Hospital in 1957.

“Joe was in the hallway with his back to me,” Weldon remembered. “I walked up and tapped him on the shoulder. He turned, saw me and started crying. ‘Coach, you’re the last guy I ever wanted to see what happened to me.’ He had drank too much for too long.

“That was out of character for the Joe I knew in Sacramento. It was just tragic.”

The Batiste family, who had moved to Tucson from Louisiana in the 1920s, grew beyond Joe’s decline and death. His younger brother, Frank Batiste, would in 1949 become the first Black football letterman in UA history. Joe’s older brother, Ernie, became a supervisor in the Tucson Parks and Recreation department for more than 25 years. His nephew, Glenn McDonald, became a standout basketball player for Lute Olson at Long Beach State, and his great nephew, Mike McDonald, was a star point guard for Stanford’s Top 25 basketball teams of the 1990s.

In 1938, after 5,000 Tucsonans watched Joe Batiste break the national high school low hurdles record at Arizona Stadium, the Star’s Vic Thornton wrote: “Batiste is the greatest track prospect in America.”

Sadly, it became a story about what might have been.