The timing of Ernie McCray’s record-setting UA basketball career was, shall we say, not favorable.

The Wildcats set a school record with 16 consecutive losses in McCray’s junior season, 1958-59. They were in the middle of what would become an 0-15 streak against Arizona State. Attendance at once-packed Bear Down Gym often plunged to fewer than 1,500.

When McCray scored the still-standing school record of 46 points against Cal State Los Angeles on Feb. 6, 1960, attendance was listed at 2,055. Yet five nights later, Meadowlark Lemon and the Harlem Globetrotters sold out Bear Down Gym, about 4,000 fans, in just 13 hours.

But memories of that long-ago night have not dimmed.

“I couldn’t miss,” McCray said in February. “The crowd was yelling, and I didn’t realize I had broken a record until after the game, and then I was mobbed by all these kids. I always remember these kids, and they were just holding on to my arm. I couldn’t sign their autographs because they were hugging my arms. That was just an incredible evening.”

An Arizona Daily Star headline tells of Ernie McCray’s record-setting performance on Feb. 6, 1960.

It has taken 60 years for McCray’s UA basketball career to be fully appreciated. He was not inducted into the school’s Ring of Honor at McKale Center until last February, even though he met the induction criteria in every category, including being the Border Conference co-Player of the Year in 1960.

McCray, who is No. 33 on our list of Tucson’s Top 100 Sports Figures of the last 100 years, said that seeing his name in the rafters at McKale Center “puts my life in historical perspective.”

Now 83, living in San Diego after a long career as a school teacher and administrator, McCray told me he is not bitter that it took so long to be recognized for a three-year career in which he left the UA as its career scoring leader.

It wasn’t as if no one was paying attention when the 6-foot-5-inch Tucson High School graduate scored a school-record 1,349 points from 1956 to 1960. In February of '60, the Star wrote:

“The next Arizona basketball record book should carry the byline — By Ernie McCray. The only records he’ll miss will be for free-throw shooting percentage and personal fouls committed.”

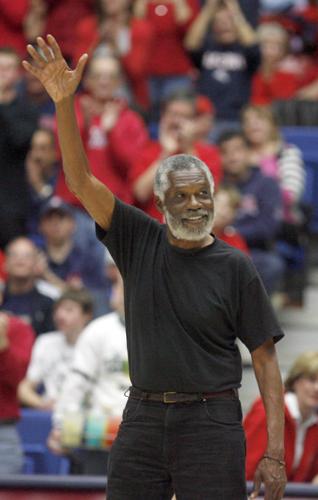

Ernie McCray, seen in McKale Center in 2010, recently was inducted into the ring of honor.

After his eligibility expired, McCray became the school’s first Black basketball player to earn a degree. He also set 12 UA basketball records.

McCray, who was raised by a single mother in an impoverished area west of the UA campus, was married and had three children during his college days. He worked as a janitor, among other jobs, to make ends meet.

McCray recently posted a Facebook photograph with his six children. He wrote: “Nothing has fulfilled my life more than being a father. Being I father, I think, is one of the wonders of the world.”

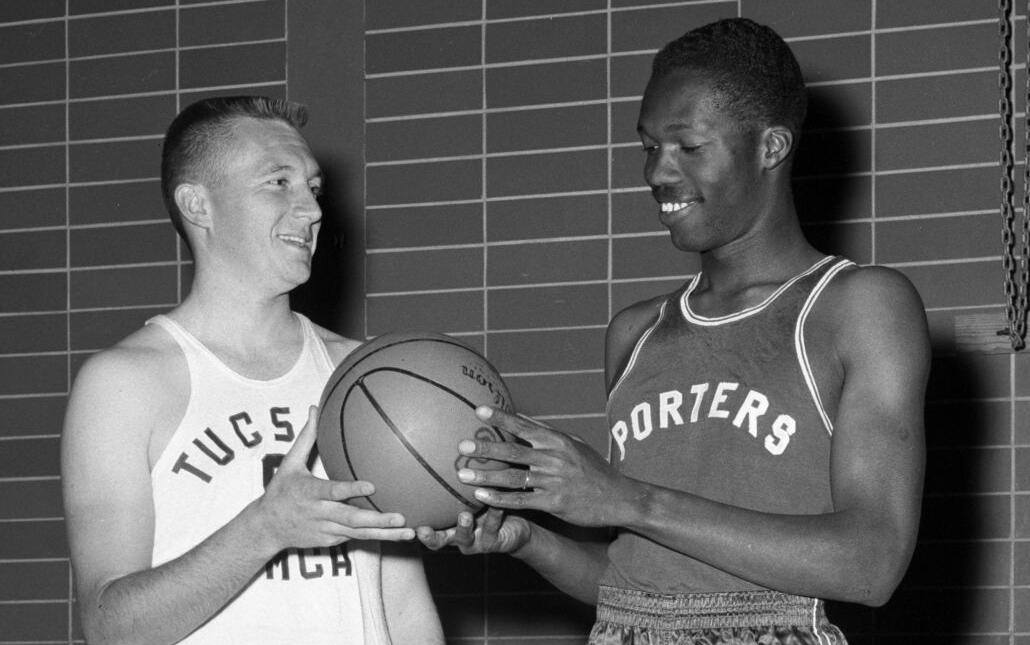

After a productive basketball career at Tucson High, McCray was not initially recruited by Arizona or ASU. He planned to play at Eastern Arizona College his freshman season, 1956-57. But while playing basketball at the YMCA that summer, Arizona freshman basketball coach Alan Stanton asked McCray if UA coach Fred Enke had spoken to him about being a Wildcat.

There had been no communication. Enke had recruited only one Black player in more than 30 years, Phoenix Carver High School’s Hadie Redd, who played for Arizona in 1954 and 1955.

Stanton said he would talk to Enke and get back to McCray. A day later, Enke offered McCray a scholarship.

What happened over the next few years became a compelling part of UA basketball history.