Carl Cooper broke his collarbone playing football at Tucson High and later broke his nose while a running back at Arizona.

What didn’t break was his spirit of achievement. After leaving the UA, Cooper figured out a way to pay for tuition to enroll at USC and earn a master’s degree. He figured out a way to make the most of his service in World War II, becoming a lieutenant after three intense months in Officer’s Candidate school.

The son of an electrician at the University of Arizona, Cooper completed World War II in the front office at the air service command in England and returned to Los Angeles to become a coach and teacher at El Monte High School.

But when Arizona track coach Limey Gibbings retired in 1950, UA athletic director Pop McKale targeted one man in his coaching search: Carl Cooper, who first met McKale a generation earlier while shagging foul balls and returning them to the UA dugout, a bat boy McKale never forgot.

Cooper, who is No. 78 on our list of Top 100 Tucson Sports Figures of the last 100 years, not only became Arizona’s track coach, but was an assistant football coach for 15 years and a full-time professor.

They don’t make coaches like Carl Cooper any more.

In 1995, I visited Cooper at his ranch in Patagonia where, at 77, he raised peacocks, emus, goats, turkeys and goodwill.

“I knew what I wanted to do from the time I was 9 years old,” he said, telling stories about his days at UA baseball games, hoping someday to be the next Pop McKale. “I never made much money, but I had a wonderful life.”

Cooper was not the next McKale, but the legacy he left in Tucson sports history earned a place of its own.

He recruited and helped develop three Olympians: distance-running bronze medalist George Young of Silver City, New Mexico; long-jumper Gayle Hopkins from a Colorado junior college; and silver medal high-jumper Ed Caruthers from Los Angeles.

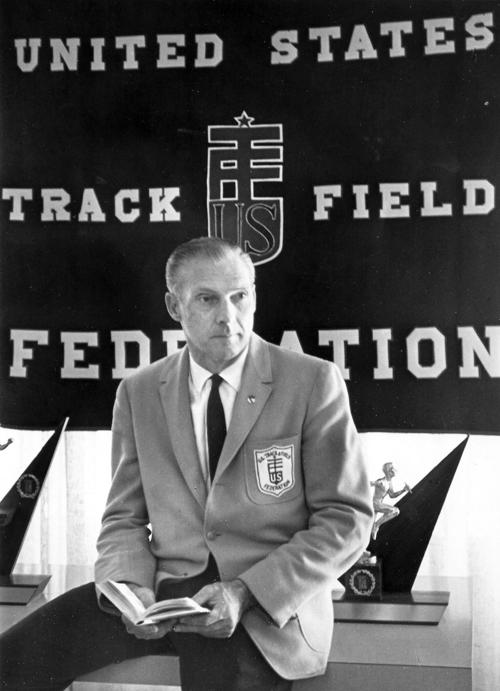

Cooper did his job so well that in 1969 the U.S. Track and Field Federation hired him to be its executive director, which led to Cooper’s selection to the International Olympic Committee, a role he served for a decade.

He didn’t want to leave his hometown, so Cooper successfully persuaded the USA Track and Field Federation to move its headquarters to Tucson.

Not bad for someone who grew up in an old adobe home on the edge of the UA campus and followed a dream and became a world traveler.

“Carl was a taskmaster,” said Dave Murray, Arizona’s long-time head track coach, who was recruited by Cooper in the mid-1960s. “He was a coach, a trainer, a psychologist, a tutor, a father figure. In those days, coaching was all of those things. Carl was all things.”

Cooper was among the UA coaches of the 1950s who actively recruited Black athletes for the first time. He signed and became a confidant of Lou Owens, a sprinter from Long Beach Poly High School who would set Arizona’s record in the 100-yard dash.

But even in 1953, when Arizona competed in a dual meet at Arizona State, Owens was not allowed to stay in the UA’s team hotel in Tempe. Decades later, memories of that night — and those when Owens was not allowed to lodge in team hotels in Texas — still bothered Cooper.

“I felt bad because I honestly didn’t think I realized what he’d be facing when I brought him here,” Cooper said in 1995. Cooper would not eat in the team hotel but would eat elsewhere with Owens.

“Carl was a good man,” said Murray, who retired from the UA 20 years ago. “He did things the right way.”