Long after Roland LaVetter coached Pueblo High School to back-to-back state basketball championships, long after he left Pueblo to teach, coach and serve as Rincon High’s athletic director, he got a call asking if he would be interested in returning to Pueblo.

This was 1991. It was 13 years after Pueblo’s 28-0 team finished No. 4 in the nation.

LaVetter knew he couldn’t coach the Warriors because his former assistant, Barry O’Rourke, coached the boys team.

“Oh, no,” he was told. “We want you to coach the girls team.”

The particulars were not inviting. Pueblo had gone 3-19 that year. It had no returning players over 5-feet, 2-inches. They would be lucky to win a game in 1991-92.

And so the man whose ’78 Warriors would be chosen as Tucson’s prep basketball team of the century said of course he would do it.

The Warriors went 0-20.

“I enjoyed that season as much as any I ever coached,” he said. “We may have lost games, but it didn’t feel like we were losing anything.”

This is the essence of Roland LaVetter, who will be honored Tuesday at 5 p.m., when Pueblo High School names the facility in which he coached during the 1960s, 1970s and 1990s “Roland LaVetter Gymnasium.”

This isn’t so much about the winning. To LaVetter, it’s about the young men and women he coached.

One day last week, long-time Tucson police Detective Calvin Fuller sat in the LaVetters’ midtown living room with Roland and his wife, Beverly, and remembered the day as a Pueblo High freshman that he met LaVetter.

“He introduced himself and asked if I was going to try out for the freshman team,” said Fuller, who was then 6-feet 1-inches and built like a ballplayer. “I said, ‘No sir, I have never played organized sports.’ I had no intention of playing basketball.”

Four years later, after LaVetter advanced from freshman and JV coaching positions, Fuller, a young black man from Tucson’s lower-economic South Park neighborhood, was chosen to the All-City basketball team and the Warriors became Class A division champions.

But it wasn’t really about basketball.

“We’ve never lost touch,” says Fuller. “When I graduated from the Police Academy, the only two people I told were Roland and Beverly.

“When I retired after 35 years on the TPD, guess who was there to see me? Roland and Beverly.”

There were a lot of Calvin Fullers in the coaching career of Roland LaVetter, the son of a long-time Tucson justice of the peace who moved to Tucson from Chicago in the 1930s in hopes his tuberculosis would respond better in a desert climate.

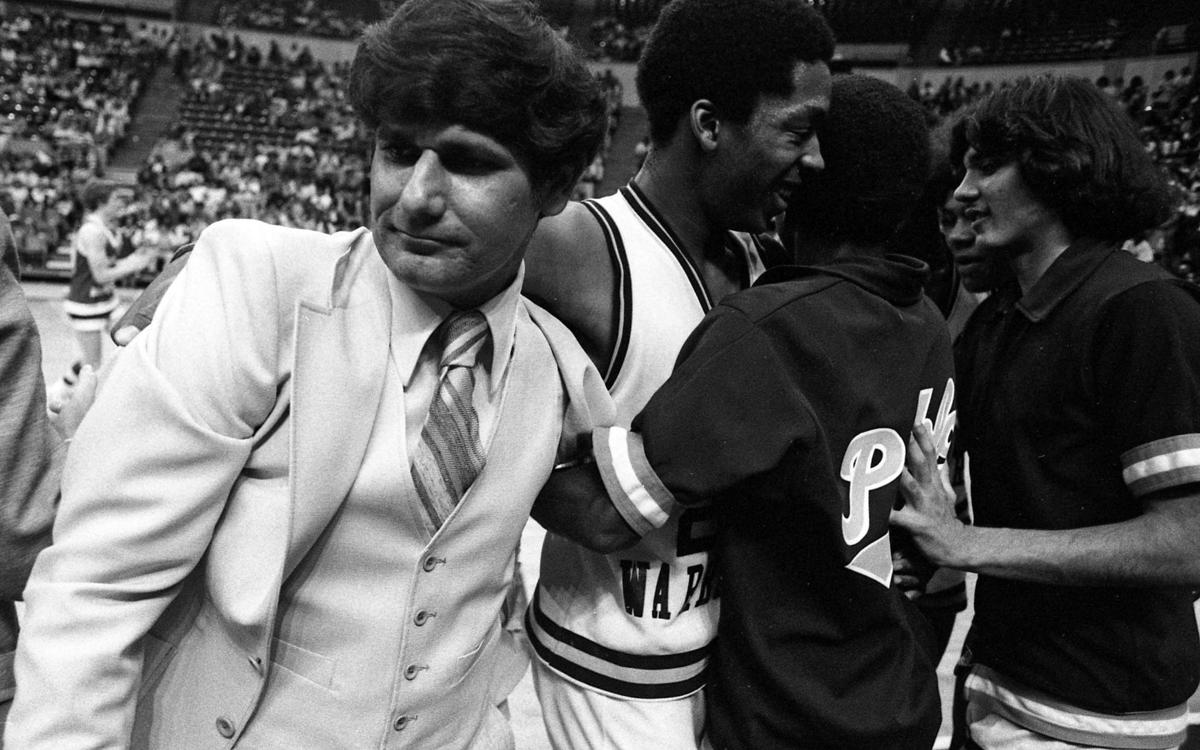

At Tuesday’s gymnasium dedication ceremony, Lafayette “Fat” Lever, star of Pueblo’s ’77 and ’78 state championships, a two-time NBA All-Star, will be front and center, flying in from Denver for the occasion. LaVetter and Lever have known one another since Fat was 9, about the time LaVetter became Pueblo’s varsity basketball coach.

The newer, North gymnasium at Pueblo is named after Lever. Now the South gym, where LaVetter coached, will bear his name.

“I saw how many lives my dad touched; I can’t tell you how many of his kids stayed in our back bedroom over the years,” says Lance LaVetter, the only son of Roland and Beverly, who has been a coach at New Mexico State, Washington, Portland and St. Louis, and is now director of operations for the University of San Diego basketball team. “I remember those game nights when we would take the whole team to the old Big A restaurant, or McDonald’s, and buy everybody dinner.

“I’d ask my mom who was going to pay for this and she would say, ‘We got paid today. We’ll make it work.’”

Rich Utter, who was the JV coach for LaVetter at Rincon and succeeded him as Rangers’ boys coach 30 years ago, will speak at Tuesday’s ceremony. Their relationship endures. LaVetter, at 79, still goes to the old Rincon gym to watch Utter’s teams play.

“Roland loved practices, he loved working with the kids,” says Utter. “That was more important to him than the games.”

When Pueblo High School conducted a food drive in the 1970s, LaVetter wasn’t sure the food would be properly distributed. He often drove past Santa Rita Park en route to school and worried about the homeless people.

“My dad picked up the canned goods himself and drove to Santa Rita Park,” Lance remembers. “He went up to every person and gave them food. That’s what I remember as much as any basketball game.”

LaVetter wasn’t an easy touch. Some of his practices would go three hours. His teams practiced on Christmas mornings. Fuller remembers some of them as “boot camps.”

“But what I liked about coach is that he was fair. He treated a third-team player the way he’d treat a starter. We knew he wanted the best for us.”

As a junior, Fuller experienced some problems at home, and it didn’t take LaVetter long to figure it out. He called Fuller into his office and asked if he could help.

“I told him, ‘I’m OK, there’s no problem,’” Fuller says now. “But he knew. He made it a point to check on us off campus, too. He told me, ‘If you need a place to stay, you can stay with us as long as you need.’ From that day, I knew I could trust him with anything.”

Tuesday, 52 years later, Fuller and his coach will return to their old high school gym, winners not only in basketball, but in life.