At the age of 20, Dick McConnell played shortstop for the Topeka Owls, a Class D baseball franchise in the old Western Association. He spent the summer of 1950 playing against the Salina Blue Jays, the Leavenworth Braves and the Joplin Miners.

“I was going to be a ballplayer,” he told me a few years ago, sitting in his favorite place, Kappy’s on North Wilmot road, sipping a beer — although he made me promise I wouldn’t write that he was sipping a beer.

“The Cubs paid me $1,700 and bought me a Buick,” he said. “I didn’t see anything stopping me from playing at Yankee Stadium someday.”

As with any good storyteller, Dick McConnell had a punchline for his I-want-to-play-for-the-Yankees tale.

“One day we were playing in Joplin, and they had this 18-year-old kid at shortstop that everybody was talking about,” he said. “I was hitting .221 at shortstop, but this kid was hitting .383, was the fastest runner in the league and hit the ball a mile.

“It was Mickey Mantle. I knew then I’d better come up with another plan.”

By the time he was 30, McConnell had moved to Tucson and became a junior varsity baseball and basketball coach at Rincon High School. Baseball was still his game, but basketball would be his future.

When Sahuaro High School was built in the late 1960s, McConnell was one of 126 applicants to be the head basketball coach. The principal, Hank Egbert, told me that as soon as he interviewed McConnell he knew the other 125 guys didn’t have a chance. “It was as plain as day,” Egbert said.

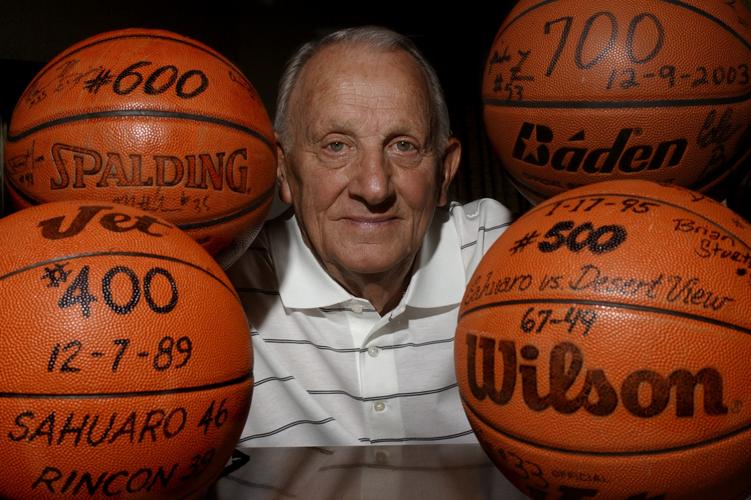

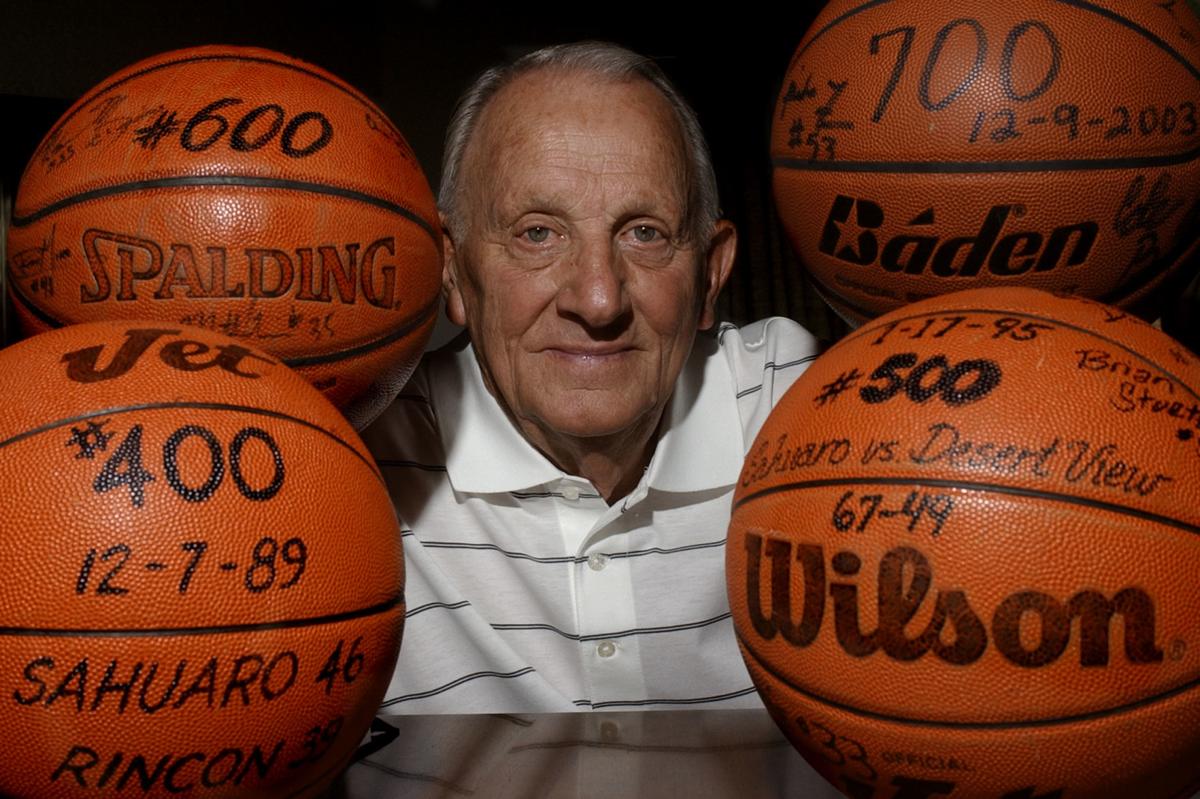

Dick McConnell, calling to his team from the bench in 1999, went 5-15 in his first season at Sahuaro. It was his only losing season in 39 years, during which he won four state titles.

A year after Sahuaro opened, McConnell coached the Cougars to the 1970 state championship. He did it again in 1982, 2000 and 2001. When he retired a few days before the 2007 season, he had coached Sahuaro to 774 victories, then the most by any coach in Arizona history.

Tucson became his Yankee Stadium. The shortstop from Washburn University became a legend in this town, known as much for his manner and his modesty as for his unrivaled coaching success.

When he died Tuesday morning at the age of 89, McConnell left a legacy like few others in the history of Tucson sports.

“We were sitting in Kappy’s one day — at Dick’s favorite table — trying to figure out exactly how many wins there have been from his coaching tree,” said Bob Vielledent, who spent 21 seasons on McConnell’s Sahuaro coaching staff. “We came up with 4,000.

“Really, 4,000.”

Dick McConnell, left, with his son Rick McConnell before the start of a basketball game between Dick’s Sahuaro High and Rick’s Mesa Dobson, Dec. 5, 1989.

And it’s probably true. McConnell’s son, Rick, has coached more than 600 victories at Mesa Dobson High School, and then come Sahuaro’s Jim Scott with more than 300, Sahuaro’s Steve Botkin and Pima College’s Brian Peabody, both with more than 500, and on and on with Pete Fajardo, Gary Lewis, Jim Ferguson, Rick Gary and Vielledent himself, who coached Sahuaro to 17 victories when McConnell’s ulcers were acting up and he had to go home for the night.

Ferguson, who played on McConnell’s first three Sahuaro teams, including the 1970 state champs, coached three state championship teams at Santa Rita. In February 2000, he found himself matched against his mentor, McConnell, in the state semifinals at Catalina High School.

It would be a game that defined McConnell as much as any of his 774 victories.

“At the time, it was as serious as any rivalry in Tucson for many years,” Ferguson remembers. “We lost a really tough game, but after, we still all went over to Kappy’s, sat down and enjoyed the camaraderie of the Sahuaro coaches. It was the toughest loss I ever went through, but I was still happy for him. He would’ve felt the same for me. We were friends first, and that’s what Coach McConnell always taught.”

For 20 years, Kappy’s was the featured gathering place for Tucson’s prep basketball insiders. McConnell and Vielledent discovered it, a safe place to blow off steam and not be seen by high school players and their parents.

On any Tuesday or Friday night during the basketball season, you could walk through the door at Kappy’s and see the Sahuaro staff, the Sabino staff, David Ginn and the Palo Verde staff, referees and anyone who wanted to feel like they were part of something grand.

It all spun on McConnell, a welcoming soul, a driver’s ed teacher and basketball coach who made it work.

“I never met anyone who didn’t like Dick,” said Vielledent. “He was such a good communicator; the kids loved him and so did the parents and the faculty. He was never a coach who yelled or demeaned the kids. He was one in a million.”

Talk about humble roots: before being hired at Rincon, McConnell broke into the coaching business at Narka High in the middle of nowhere in Kansas, a school of 27 students. His first job in Arizona was at Tombstone High School.

He didn’t get a crack at the Sahuaro job until he was 39. He coached there for the next 39 years. On the day of the dedication of “McConnell Gymasium,” he was as humble as ever.

“We went 5-15 my first season,” he told the crowd. “I would’ve understood had they not kept me.”

It was the only losing season in McConnell’s 39 years at the school.

I last talked to McConnell in the gymnasium at Rincon High on a random Tuesday night. I was attending a girls basketball game. He was in a wheelchair, accompanied by Clarine, his wife of 63 years.

I asked him what he was doing at a girls basketball game at Rincon.

“I came to watch Steve Ganson referee,” he said. “I heard it might be his last game, and I wanted to let him know how much I appreciated him.”