A group of Wildcats basketball fans gathered around a television in the lower concourse of McKale Center and watched nervously as the nationally-ranked UA women’s team battled Oregon on the road. When Bendu Yeaney splashed a game-tying 3-pointer late in the game, they cheered.

It was one of those rare nights where both UA basketball programs were playing on the same night — Arizona’s women in Eugene, and Arizona’s men at home for a game with Utah.

“This game has come such a long way for us since I played,” one voice said amid the cheers.

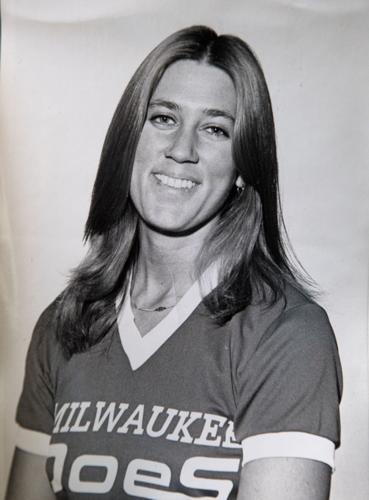

Lynda Phillip, an “A-Team” security guard who has worked UA men’s basketball games at McKale Center for more than a decade, has a place in women’s basketball history.

When she talks about “us,” she doesn’t mean the Wildcats. She means women.

The 69-year-old Phillip was part of the first professional women’s basketball game ever played on American soil. The 6-foot-1-inch Phillip — then Lynda Gehrke — won the opening tipoff in a game that her Milwaukee Does lost to the Chicago Hustle, 92-87. The Dec. 9, 1978 game drew 7,824 spectators at the renowned Milwaukee Exposition, Convention Center and Arena (MECCA). The game was featured on the “CBS Evening News” and written up in the New York Times.

“It was amazing being recognized,” said Phillip, a Catalina High School and Pima College graduate. “Like, we meant something and we were important. Nobody ever came to our games when I was in college, and there were some really talented players. … I’m a talker when I play. I learned how to talk (expletive) while playing with the men. Women didn’t have that, so I took that to the women’s game. But that game? Nobody could hear me, I couldn’t hear myself and the big, bright lights were almost blinding.”

Added Phillip: “It was scary because we never played in front of people like that. But we were ready and so excited. It was heaven. Like, we finally made it.”

The eight-team WPBL featured the Does, Hustle, Dayton Rockettes, Houston Angels, Iowa Cornets, Minnesota Fillies, New Jersey Gems and the New York Stars. Milwaukee finished the 1979 season with an 11-23 record and a last-place finish in the Midwest Division. The league added the Washington Metros, Philadelphia Fox, St. Louis Streak, Dallas Diamonds, California Dreams, New Orleans Pride and San Francisco Pioneers before shutting down in 1981.

Phillip said she initially made $240 per game. But by the end of her first and only season in the league, she said, “they weren’t paying us anymore.”

It wasn’t the first time she felt degraded.

Finding basketball, earning respect

Phillip attended Catalina High School, which didn’t have a girls basketball team. Instead, she played softball and competed in track and field. She found basketball only after enrolling at Pima College.

“When I got to junior college, the coach would always chase me down when I got to the gym and would say, ‘Come play basketball for me,’ because I was so tall and athletic,” she said. “So, I finally said, ‘OK,’ and I didn’t really start playing until I was in junior college. But I fell in love with it and that was all she wrote.”

Phillip would play pick-up basketball at Bear Down Gym against men. There, she said, she was disrespected until she proved she could play.

Simply earning a spot on the court was an everyday battle. Every player who competed in the games wrote their names on a chalkboard to claim a position. Gehrke would often look over and see someone else’s name instead of hers.

“If I didn’t stand there and guard it, they would erase my name,” she said. “It was a fight for me to get on a team.”

Once Phillip displayed proved she could compete with anyone in the gym, however, “they started picking me over the guys,” she said.

Lynda Phillip, front row and third from the left, poses with her fellow Milwaukee Does in a 1978 team photo.

“They respected me enough and realized, ‘Lyn can play,’ and if I made a good move on a guy and scored on him, not only his team but my team would say, ‘Why did you let her do that to you?,’” she said.

“Almost like he let me do it. I knew the next time down the floor, I was getting knocked down. Sure enough, I would go down the court and he would just pummel me. I would get back up and off I go again.”

During her final season at Pima, Phillip averaged 22 points and 12 rebounds per game. She set the school’s single-game scoring mark with 50 points.

Phillip briefly served as an assistant coach at Pima before accepting a scholarship to UNLV. There, she quickly discovered the discrepancies between the men’s and women’s basketball teams.

The women’s team traveled via buses or vans, while the Runnin’ Rebels men’s team took a charter plane to every road game.

Once, both programs were scheduled to play in Hawaii in the same week. They planned to share a flight from Las Vegas to Honolulu.

“But guess what? The women’s team got kicked off the plane because there were so many (men’s) boosters that wanted to go, so we had to fly commercial,” Gehrke said. “We were always at the bottom of the barrel.”

In Hawaii, Phillip and her teammates stayed in a “one-story shack, while the men’s team was in the high rises with all the boosters.”

“They were having parties and the boosters would keep their doors open and you’d see them go, ‘Oh there’s my favorite player!’ You could see them putting money in their hand and giving it to the players,” Phillip said. “You could see it.”

Phillip eventually transferred to Colorado, where she was named a team captain.

After her final season, Phillip was caught in a dilemma: What now?

“I was sad, because I didn’t have basketball anymore after college,” she said. “What was I going to do? There were a lot of tears and heartache.”

Turning pro

Eventually, Phillip learned about the WPBL and showed interest in joining the league.

There would be no draft-night drama. Phillip learned she was drafted when one of her college teammates told her.

“I said, ‘That’s a cruel joke and I don’t find that funny at all,’” Phillip said. “I actually got mad at her, but sure enough, I got a letter in the mail to come try out for the Milwaukee Does.”

Milwaukee was the perfect spot for Phillip to start her pro career. She was born in the city, and lived there for three months before her family moved to Tucson.

“It was like my birthplace was calling me home,” Phillip said.

At the tryouts, the time spent playing and conditioning in the Colorado altitude was used to her advantage. Phillip said she was “dancing circles around everybody.”

“I have good wind because of the mile-high (altitude),” she said. “Then I officially made the team.”

Along came the fame.

“The first time I was asked for an autograph, I was like, ‘Me? You want my autograph? OK.’ There were just so many new things for a female,” Phillip said.

Once the 1979 season concluded, Phillip was traded to New York. She told the team that she’d rather play for the new San Francisco franchise, in part to be closer to home. New York wouldn’t budge.

“Because they wanted me playing for them, not against them, which was a compliment, but it wasn’t what I wanted to hear,” she said.

Lynda Phillip, then Lynda Gehrke, played at Pima College, UNLV and the University of Colorado before playing professionally in both the United States and France.

Phillip returned home to Tucson and questioned what her basketball-playing career would bring next. She had no idea how far she’d go.

A ‘parrot’ in France

Back in Tucson and contemplating her future Phillip continued to play basketball. Following a pick-up game at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, she was approached by a man who offered to help her land a spot overseas.

“At first, I thought he was hitting on me and trying to get my number. But a month later, he called me and said there’s a team in France that wanted me,” she said. “Didn’t want to go to New York, because what’s a little girl from Tucson doing in New York? But I decided to go to France and I can’t speak French.”

Phillip found a place to live outside of Paris, got a job teaching aerobics classes during the week and taught children about basketball when she wasn’t practicing or playing games. There was one rule for Phillip’s teammates and coaches: Nobody could speak English to her.

“So I became a parrot,” she said. “I listened, repeated it and if I was wrong, they’d correct me. I realized that I had a handle on the French language when I started dreaming in French.”

Phillip tore her ACL while playing overseas, underwent surgery and endured physically and emotionally taxing rehabilitation. She returned to the court, but found herself “babying” her leg.

“That’s when I thought, ‘I can’t play anymore.’ Plus, my passport was going to expire soon, so I thought it was time to go home,” she said.

Phillip retired from playing basketball in 1985, returned to the Old Pueblo and worked for Tucson Parks and Recreation.

Phillip coached her two sons, Jeffrey and Paul, at the downtown YMCA. As the only woman coaching against men, Phillip felt the same lack of acceptance that fueled her at Bear Down Gym more than a decade earlier.

“I’m a woman coaching these boys teams, and these men thought they knew more than I did,” Phillip said. “My competitive level is off the charts, so we went out there to play and we killed their teams. … They all thought I should be barefoot and pregnant at home instead of coaching these kids. But we would win and it’s because these kids were really good.”

During a postgame handshake to end the season, the opposing head coach walked over, “like he was revealing some bad secret,” and said the other coaches nicknamed her “Warrior Princess.”

“I thought, ‘Damn, that’s a compliment. That’s right, I am the Warrior Princess,’” she joked.

The evolution of a game

Phillip doesn’t coach anymore, but says she’s fond of UA women’s basketball coach Adia Barnes and how she’s lifted the Wildcats’ program to national relevance.

“It’s fantastic that (Arizona) got her. She’s doing great with them, how can you dispute that?” Phillip said. “Her and her husband are pulling great players from overseas. And I hear she’s up for a (Naismith) Coach of the Year vote, too? She’s doing a great job.”

Arizona men’s basketball coach Tommy Lloyd said he would love to meet the security guard who is normally posted near the visiting team’s locker room.

“This community is filled with a lot of cool things like that,” he said “I’ve met a lot of people who have unique affiliations with the game of basketball just in my time in Tucson, and I love it. That’s really cool.”

Times have changed, albeit slowly, since Phillip won the opening tipoff that night at the MECCA. College and professional women’s basketball is regularly shown on national television. Barnes and the Wildcats rank second in the Pac-12 in attendance. Earlier this month, the UA drew a regular-season-record 10,413 fans to its home game against Oregon.

Phillip was wrongfully unpaid during her only professional stint in the United States. Now? The highest-paid players in the WNBA earn just over $228,000 per year.

“It’s about time,” Phillip said. “We play the game well and we play with fundamentals. The men? They’re all about the fancy stuff and dunking.”

Phillip stands in the hallways of McKale, feet from the court — and close to the memories of her time as a basketball pioneer.

“I never knew life was going to take me down that road,” she said. “I’m just very fortunate.”