First, the story about the hat, which is about as well-known as the hat itself.

When Trooper Taylor was a young boy, one of 16 children to Bonnie and Gloria Taylor, he’d flip his father’s hat around just as he was about to leave for work, get a kiss on the forehead and tell his father that he loved him.

Until the age of 12, that was their routine. And in a house of more than a dozen, any special moment is magnified exponentially.

One day, on the verge of becoming a teenager, young Trooper was too cool for that kid’s stuff, and he said as much to his father.

“He laughed, and he rubbed my head, and that was the last time I saw him alive,” said Taylor, the colorful Arkansas State assistant head coach who will bring the Red Wolves into the Nova Home Loans Arizona Bowl on Saturday for a matchup with the Nevada.

Taylor remembers his football coach walking onto the field that day, propping up his older sister Tracy, and, he recalls, “I was thinking surely nobody did something to Tracy; we roll 16 deep.” The coach brought Trooper’s brother Carlos together with them and delivered the news. Bonnie Taylor had died that day of a sudden heart attack, walking from one full-time job to the next.

There were a lot of mouths to feed in that household, and Trooper Taylor is still convinced his father worked himself to death.

So when he found himself in his early 40s and doing the same thing — working himself to death as one of the premier assistant coaches and recruiters in the game, spending more time with other people’s children than his own, coaching Dez Bryant to future fame at Oklahoma State, winning a national championship at Auburn — Taylor took a step back.

And then he took a leap of faith.

•••

Taylor’s head coach, Blake Anderson, was once the skinny walk-on wide receiver at Baylor, where Taylor was a defensive back. This was the late-1980s, when football was king, and football players in Texas were gods.

You can understand how football grew to consume them.

Like Taylor, Anderson had once found himself at a crossroads, dedicated more to his career than his family, his kids on the backburner, his wife alienated. When Anderson got the head coaching gig at Arkansas State in 2014, he vowed to be different, both for himself and his family — and for his school, which had undergone four head coaching changes in four years.

Anderson was unabashed when he declared his priorities: Faith, family and football falls into place. He was not going to compromise on that, and the school knew it, and he made that much clear to his assistants as he started to build a staff.

One of the most important pieces: Taylor, who was burnt out from coaching at Auburn from 2009-12, even if he’d achieved more as a coach than he’d ever planned. For all the big homes and flashy cars and bling, he wasn’t happy. There were whispers about recruiting violations that ultimately went unfounded, and flirtations with other SEC schools.

It was a stressful life. The stakes were high. One time, Taylor lost a recruit because the hotel that housed him didn’t stock his room with toilet paper.

“You think he was happy about having to call down for toilet paper?” Taylor said. “So what do you think I do at every hotel now? To this day, I check it. Whatever hotel room, I make sure whoever is assigned, check for toilet paper. Check every detail there is. If he’s supposed to have a king-sized bed, it better be a king.”

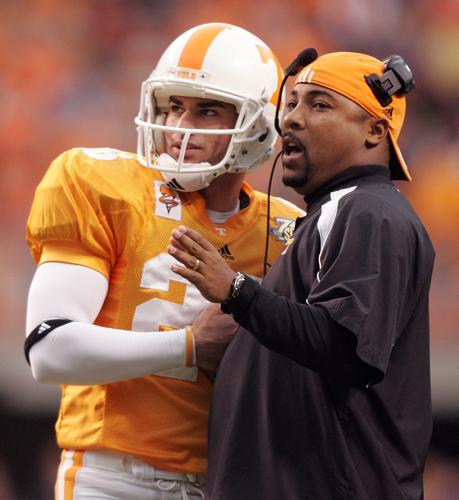

Trooper Taylor, right, has been in coaching since 1992, with stops at places such as Tennessee, Oklahoma State and Auburn.

It wasn’t just the cutthroat competition. SEC football is no joke. When you steal another team’s recruit, the fan base doesn’t just rail on a message board.

“I won’t say which school, but I was at a school where a player switched to our team, and said he was committed because of his relationship with Coach Taylor, and my wife got death threats,” Taylor said. “There was a box put on my porch that said it was going to be a bomb unless I left the other school’s recruits alone. My son was on a bus one time and a guy called my wife and told her what he had on, where he was sitting, and what he was wearing. On a field trip.”

Between the rat-racing and the star-chasing, Taylor found himself spiraling. He took a year to evaluate his options, 2013, and he rediscovered his family in the process.

One day he got an education, and his young daughter was his teacher.

“I’m driving her to school one day, and she says, ‘Do you really think we care about the cars and swimming pools? We like those things, sure. But more than anything, Blaise wants you to see him play a high school game.’ I pulled over and I had to wipe the tears from my eyes. It was like God used caller ID. He sent my 13-year-old daughter to tell me the truth.”

Ultimately, he went with his heart, and with Anderson, down to Jonesboro.

“I was so locked in on success, on how much money I could make, the emblem on my shirt — I got caught up in it,” he said. “I missed my kids growing up. I missed my wife. I watched my son play in four or five games ever. I was always on the road. We had a dog for 10 years, I can’t tell you his name. My mindset was to outwork everybody. Being at those big schools, if I’m in bed until 6 a.m., I’m doing it wrong.”

Taylor took the job at Arkansas State and has stayed five seasons, with bowl games culminating each campaign. His son, Blaise, was a four-time team captain for the Red Wolves from 2014-17, one of the best punt returners in Sun Belt history with multiple school records and a sterling academic record, which included both bachelor’s and master’s degrees before his senior season began. His daughter, Starr, is a guard on the Red Wolves’ women’s basketball team. His wife, Evi, a former Baylor track star whom he married on the 50-yard line of Waco’s Floyd Casey Stadium, is a psychology professor at the university.

And guess what?

“I still live on a golf course!” Taylor said with a laugh.

•••

He names them all, one by one, even if — nearing 50 — he struggles to remember their ages. There is a Rosalind and a Margaret, and a John and a Marjohn. Oscar, Carlos and Carmella. Tracy, Terrence, Tina and Tim, too. The youngest, or as Trooper likes to call her, “The Last of the Mohicans,” is Mekellia.

Sixteen if you count them all.

They lived in a small town, Cuero, Texas, population 7,126, “and we were 18 of them,” Taylor said.

Get this: His mother, Gloria, has 47 grandchildren.

“Growing up in that big family did make a difference,” he said. “It really shaped who I am. The standards. There wasn’t anybody in that little town who had that many people but us. The way mom and dad approached things, you didn’t realize you were doing without. They found ways to make it right and fun. Didn’t realize until I got old that everyone didn’t live like us.

“I told my mom one time, ‘I can’t wait for Christmas.’ She said, ‘Boy, Christmas is for the little kids.’ I’m like, ‘I’m seven! What’s the cutoff?’ I guess I wasn’t little anymore.”

Five years later, he grew up real fast. His father’s death hit Taylor hard.

“It was really a wake-up call,” he said. “My mom got us all together and point-blank told us we weren’t going to let our circumstances change our standard, were going to let our standards dictate our circumstances.”

The Taylors grew tighter. Gloria pulled everyone together.

She gave her children a bible verse — Romans 8:28 — that has formed the basis of Taylor’s philosophy.

“And we know that all things work together for good to those who love God, to those who are the called according to His purpose,” it reads.

That verse is prominently hung on his office wall, along with just one other quote, one that Taylor learned from former Auburn coach Gene Chizik.

“He said ‘Troop, do not let everybody else get the best of you and your family get the rest of you,’” Taylor said.

That is a lesson that Taylor has taken to heart. He may one day bounce back to the big leagues, Power 5 football, where salaries are almost as inflated as egos.

The one thing he’s learned from the jump to the Sun Belt Conference: The kids don’t change, no matter the logos on their jerseys.

“The pace has slowed down some,” he said, “but the intensity of the game? The love and passion for it? The fans, the players — they’re just as passionate about it as the guys at Tennessee. They have the same problems as the guys at Auburn. The difference is me.”

Taylor prides himself on his connection to players. Losing a recruit isn’t just a jab because a player will take his talents elsewhere. Taylor laments relationships that are no longer allowed to form.

He takes pains to show his players, many from impoverished backgrounds, what a successful family can look like. He had nearly 50 at his house for Thanksgiving. Evi has the players, every one of them, build gingerbread houses. “I’m gonna tell you who built the best house — Dez Bryant,” Taylor said. “The dude put a helicopter pad and a swimming pool on the top of his gingerbread house. Of course he did.”

Every year, they have the team over for Easter Sunday, and “you’d be surprised how many times we give kids Easter baskets and they’ve never done it before,” he said.

This, Taylor said, is the most important thing he can do.

“We try to give them a living example that everybody doesn’t have to be the Cosbys or an NFL player to be able to live the way we live,” he said. “You can make good choices, get your degree, get your education and get this life.”

He strived to impress that upon them. This can be yours. For so many of his players, he said, they never had these kind of family traditions.

Kind of like a kid putting his dad’s hat on backwards for the first 12 years of his life.

Turns out, that sticks with you.