Among the many assignments of 1970s Arizona assistant basketball coach Jerry Holmes was to make sure Coniel Norman got to campus in time for morning classes. At times, this was more difficult than recruiting against UCLA or Arizona State.

"Coniel’s family was a basketball and a rim," Holmes says now. "He grew up in a ghetto in Detroit and came to Arizona to play basketball. There have been thousands of college basketball players like Coniel. For two years, we did the best we could to get him ready for life after basketball. We knew we were going to lose him."

One of the few things "Popcorn" Norman could not do from 1972-74 was to successfully pretend that his life’s goal was anything other than basketball. He averaged a school-record 23.9 points per game.

He was probably the most popular sports figure in Tucson in the mid-’70s.

"I’d drop Corn off at the student union and he would walk across campus, check to see if I was gone, and then go straight to Bear Down Gym and start shooting jumpshots," said Holmes, one of the most effective recruiters in UA basketball history, 1972-82. "Academics wasn’t Corn’s thing. If he had stayed at Arizona for four years, he’d have broken every scoring record in the books."

A year ago this spring, Holmes saw Norman for the first time since he entered the 1974 NBA draft and left school, left Tucson, not to return for 48 years.

"I was overjoyed to see him again, but I could see right away Corn was struggling with his health," says Holmes, a retired business executive who has lived in Tucson for almost 50 years. "He was hooked up to an oxygen canister 24/7. He had difficulty moving around. It was so sad."

Norman had returned to Tucson with Stacey Snowden, daughter of Fred Snowden — the coach who recruited Norman from Detroit’s inner-city Kettering High School in the spring of ’72. Stacey is hoping to do a book on her late father’s coaching career, specifically the "Kiddie Corps" years, of which 1972-73 freshmen Eric Money, Al Fleming and Norman became the first Wildcats to play at McKale Center.

"When I left Corn at the DoubleTree Hotel that day, I thought it might be the last time I would see him," said Holmes. "It was good to see that he was at peace with himself. He was married, he had found God and overcome so many problems — homelessness, drug addiction, poverty."

Last week, Norman died in Los Angeles. He was 68. Two weeks earlier his wife, Maria Lewis-Norman, died. It was comforting to Holmes and to Coniel’s many friends that he is no longer alone, no longer suffering.

Sadly, Norman’s legacy wasn’t his NBA career. He played parts of three seasons for the 76ers and Clippers. His NBA career was over after 99 games. He enlisted in the Army, served four years in Germany and later played a few years in the EuroLeague, although there is no official listing of how long he played, or how successful he was.

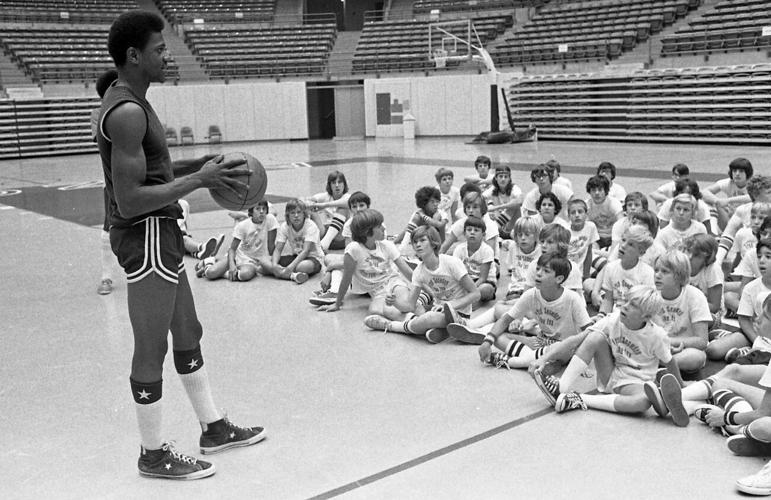

Coniel Norman (22) played 99 NBA games following a brief but stellar UA career.

"One of the reasons Coniel didn’t stick in the NBA is because there were so few (18) teams then. Now there are 30 teams," says Holmes. "Rookies had difficulty getting any traction, and Coniel needed time to work on defense. There was no G League for him to get more developmental time."

The other reason Norman’s NBA career stalled was because the league didn’t implement the 3-point shot until 1979, a year after he was released by the Clippers. Imagine if someone with Norman’s shooting chops came along today.

Today’s Coniel Norman might play 10 to 12 years and earn $100 million.

"Corn could shoot with anybody." says Holmes. "I think he’s the greatest pure shooter Arizona has ever had, even better than Steve Kerr."

Life after basketball wasn’t good to Norman, who lost touch with his family for almost 25 years. At the time he was reunited with his sister Renee in 2010, he was living on the streets of Los Angeles.

Renee made contact with Norman and assisted in his move home to Detroit. For a few years Norman lived in a $23 million government complex to house homeless military veterans. Just as his life got back on track, his health began to fail.

In 1981, on an Arizona road trip to Kansas State and Kansas, I sat with Fred Snowden in his Manhattan, Kansas, hotel room and asked about Norman. Snowden remained dispirited about Norman’s brief basketball career. He did not know where Norman was living or what he was doing.

"I became good friends with Corn’s high school coach, Charles Nichols; we both went to Wayne State," Snowden told me. "When I recruited Corn from Kettering High School, the link to Coach Nichols was how I got him away from the Big Ten schools. I treated him like a son."

Nichols helped funnel both Norman and Money to Arizona, where Snowden was the first Black head coach at a Division I basketball program.

"Nichols graduated from the Tuskegee Institute and had the best interests of his young Black players in mind," Snowden said. "We would have never had a chance to get Corn without Coach Nichols’ guidance. In retrospect, keeping 'Popcorn' in Tucson for two years was as good as we were ever going to do. The NBA created the ‘hardship’ draft about that time, and that was music to his ears."

Norman never played in an NCAA Tournament game at Arizona, but he scored 1,194 points, then No. 4 on the career scoring list. He scored 37 points in the historic, first-ever game at McKale Center, a sellout of 13,652 on Feb. 1, 1973.

"If the 3-point shot had been in effect, he would’ve had 47," says Holmes. "I only saw him play one better game."

In late January 1974, Norman scored 44 at BYU. He made 19 of 31 shots. Holmes estimates 10 of those would’ve been 3-pointers today.

"He would’ve scored 50 under today’s rules," says Holmes. "Maybe he was just born too soon. But the last time I saw him he was happy. That counts a lot more than all the basketball he ever played."