Danny Martin, an artist born and raised in Alabama, still remembers the first time he had Tater Tots from The Grill.

On his first trip outside of the Deep South — to visit a friend attending the University of Arizona — Tucson’s oddball authenticity won him over. He enrolled in the university’s master’s program for printmaking.

Now, almost 10 years later, The Grill and its Tater Tots are gone, but Martin still recalls those golden potatoes he enjoyed on his first trip to the Southwest.

“I thought, ‘I haven’t had a bowl of Tater Tots since junior high,’ ” Martin said. “You could still get a really great Tater Tot, and it’s a simple thing done well. I love simple things done well.”

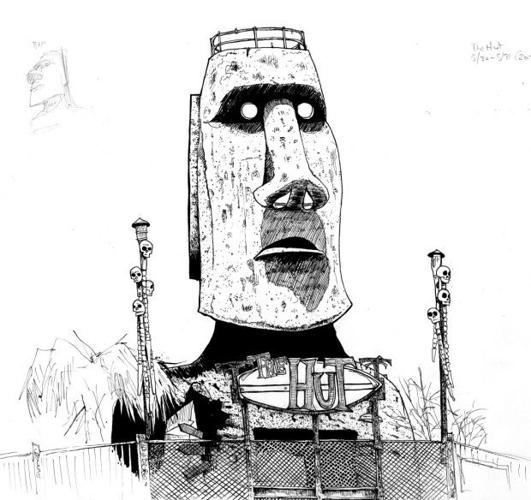

That’s how Martin does art. He adds quality to simplicity with both drawings and mixed media, using pens and pencils on paper and often skipping color. He prints his work as stickers and T-shirts, among other forms. His art shows up around the city. On the side, he teaches a screen printing class at Pima Community College.

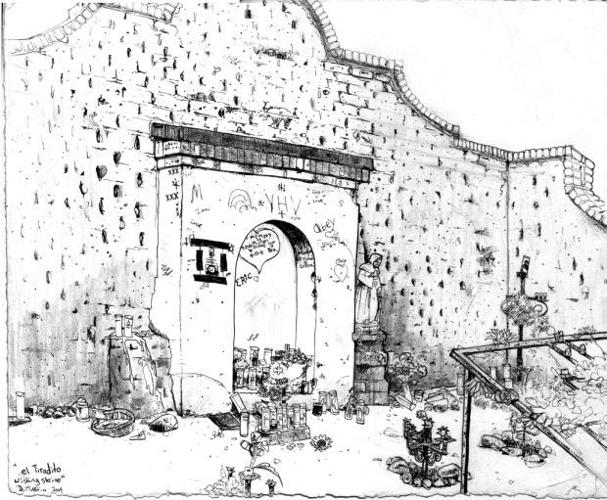

The black-and-white drawings in the “Tucson Sketchbook Project” are part of his latest undertaking. The project is inspired by Eugene Atget, a French photographer who documented old Paris before modernization and World War I. Martin feels a similar approach in his work as change sweeps through Tucson.

“That’s where my interest in doing the series is, is that we are changing pretty fast,” Martin, 34, said. “Wherever Tucson goes, I’m documenting what I care about now.”

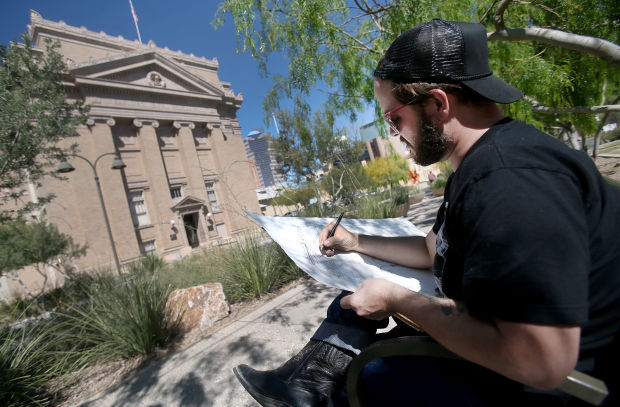

For the last nine months, Martin estimates that he has spent hundreds of hours camped in front of Tucson buildings, sketching both architectural icons and unassuming details that catch his eye. By November, he hopes to have sketched 100 subjects around the city to fill a letterpressed book. Right now, he has around 40 drawings.

Nick Georgiou, an artist and a good friend of Martin’s, moved to Tucson about five years ago. The night they met, Martin introduced Georgiou to Che’s Lounge, still a favorite bar and a subject in the “Tucson Sketchbook Project.”

“It brings back the amazing memories we’ve all had there, being in Tucson and finding ourselves,” Georgiou, 33, said of Martin’s drawings.

These are the buildings where some of that self-discovery happens.

Most of Martin’s sketches focus on the downtown and university areas, though he has no rule against including structures in other parts of the city. The San Xavier del Bac Mission, for example, will make the book, and he has begun venturing south to sketch places such as Teatro Carmen and El Tiradito. The project is expanding his mental map of Tucson.

“I don’t think of them as architectural drawings as much,” Martin said. “I’m treating them like they’re portraits of human beings. I’m looking at it that way whether they’re brand new buildings or old in age. I’m looking at the context of what their history is, but also like I’m meeting a person for the first time.”

Martin bikes to each spot, as he bikes most places he goes, carrying his pen, paper and a wooden board for drawing in his backpack. Sketches take anywhere from several hours for a neon sign to several days for icons like Hotel Congress or a Catholic cathedral. He always goes in person.

The first sketch in the series, Time Market, took most of a day, confronting Martin with the actual scale of his project. At a minimum, it would take 100 days of his life — one day for each subject — but Martin draws many subjects from multiple angles for several days.

He looks at Tucson as he imagines a tourist might, slowing down to explore streets and neighborhoods off his usual path. He wants to share this fresh perspective in his drawings.

During his own, early months in the city, Martin discovered Tucson’s “genuine appreciation and passion for the things that are genuinely cool.”

He lived near The Loft Cinema, a Tucson institution that blew his mind for its range of film options. In his hometown in Chilton County, Ala. — with its two stoplights, three gas stations and two lumber mills — Martin remembers mail-order as the method of choice for watching an independent film in pre-Internet days.

Martin loves Tucson’s swap meets and yard sales that remind him of home, the hot dogs with bacon that he calls an “eye opener,” and the hodgepodge of Mexican, Native American and cowboy cultures that he now features in much of his art.

“It was as weird and quirky and as wonderfully backwater as where I came from,” Martin said of his move West.

He grew up on cowboy films with hardworking parents who did not have the opportunities that they gave to him. Martin’s mother picked cotton as a girl. He says her hands are rougher than his will ever be. His father had an interest in drawing and dabbled in writing science fiction, but focused not on art but on providing for his family. Martin’s older brother and sister also drew for fun.

“He was always doodling something,” his older brother, Michael Martin, said by phone from Thorsby, Ala.

The family never questioned that Martin would become an artist. His parents gave him the freedom to live what he calls a “bourgeois arts” lifestyle.

“Whatever work ethic I have comes from them,” Martin said. “That’s because I know what a privilege this is.”

Life in Tucson was a long time coming.

“Danny had a cactus when he was growing up,” Michael Martin, 46, said. “He did a still life on it. When I came out here, I told him I could see why he loves it so much and why he stayed.”

In the desert, where there is space to breathe and slow down, Danny Martin finds similarities to life in his hometown — though he misses homemade peach ice cream and pit barbecues.

“Rural Alabama culture has the aesthetics of cowboy films and Westerns,” Martin said. “Growing up and even to this day, I don’t know how to dress up. When I dress up, it’s always country-Western.”

The family bonded over cowboy films, and Tucson’s connection to John Wayne actually calmed nerves about Martin’s move.

“It was like, ‘If it was OK for the Duke, it must be OK for my Danny,’ ” Martin said.

Today, cowboy culture, along with Day of the Dead imagery, inspires Martin’s work.

“The archetype of the personality that chooses to live in the desert out here is the same type of person who chose to live out here in the Old West days,” he said. “Pretty much you’re an individual, maybe you’re off your rocker a little bit, which can be either good or bad. … You’re trying to start a new history, which I think is a very American thing to do, to reinvent yourself.”

In that transition, Martin remembers his roots and Tucson’s. Sometimes, they are as simple as a bowl of Tater Tots.