Kathleen Sanchez will do anything for a memory.

She remembers sitting on the floor to make candied apples and helping a few of her 20 grandkids decorate Christmas stockings with glitter and glue.

“I’m all about memories; that’s all I was,” says Sanchez, 58. “I still have a lot of memories to make. As long as I have all my faculties still, I’m going to do what I can.”

Sanchez got her diagnosis of early-onset Alzheimer’s disease in 2008 after an overwhelming moment of forgetfulness. For a second, she felt as if she wouldn’t recognize her own children if they drove up to her house.

But it hasn’t stopped her.

On Saturday, Nov. 7, Sanchez will speak to the crowd gathered on the University of Arizona’s Mall for the Tucson Walk to End Alzheimer’s, as she has multiple times.

Last year, her grandson Julius Hernandez III, 18, spoke on behalf of those who care for or support someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia and will speak again this year. He is working with his grandmother to spread awareness at the walk and as the founder of a new club at Toltecalli High School.

“I don’t want to accept it, but I know I have to. ...” Sanchez says. “It will always bother me until I can’t remember for it to. It will hurt until I don’t hurt anymore, and I can’t remember to hurt.”

With good weeks and bad weeks, she can feel the disease progressing. It’s scary, but her family gets her through.

“In times when I’m just like, ‘Oh, I just don’t want to do it anymore,’” she says, “my husband will say, ‘Tell your grandkids that.’”

She still finds joy in cooking for her family and teasing her grandsons who call to check in. Sometimes, they prank call.

“We still laugh a lot,” Sanchez says. “That’s one thing that hasn’t faded at all.”

CHANGING THE DEFINITION

OF HOPE, moment by moment

With no current cure, a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s is, to many families, a diagnosis of a future without hope.

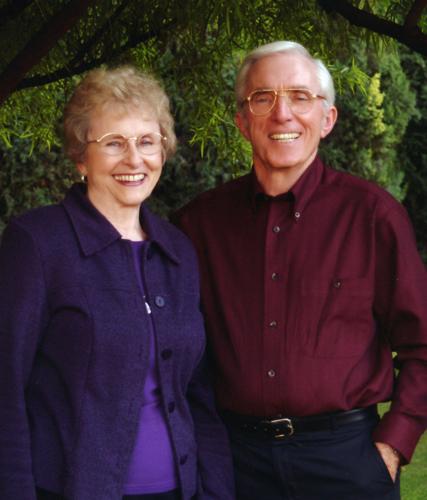

For Bruce and Norma Patrick, the diagnosis of probable Alzheimer’s came in 2001, two months shy of their 40th wedding anniversary.

Bruce was a “people person” who spent 27 years working as an administrator with Tucson Unified School District, says Norma, 84.

“He always said, ‘I’m going to beat this thing,’ and I just smiled and said, ‘Yep. We sure are,’” says Norma, who immersed herself in research after the diagnosis.

In August 2004, Norma and her three adult children made the gut-wrenching decision to place Bruce in a care facility.

She smiled that day, telling her husband she would be back after a meeting.

Then she collapsed in the car, mourning.

“On the day he was placed, I realized I will never, ever face anything more difficult, no matter what life brings, than that,” she says. “It was awful.”

The family moved Bruce three times, and Norma found solace through spiritual books, prayers and quotes. She plastered the Serenity Prayer all over her home.

“‘Wisdom to know the difference’ is the key phrase,” she says. “Change what you can.”

When Bruce died in October 2007, the couple had been married 53 years. Both are brain donors for Alzheimer’s research, and Norma has volunteered with TMC facilitating its film series “Perspectives on Alzheimer’s” for seven or eight years.

“We loved him through what he had to go through,” Norma says. “I tell people, ‘I didn’t choose Alzheimer’s to study. It chose me.’ I feel like I’m helping him and honoring him.”

Terri Waldman, the director of geropsychiatric services for Tucson Medical Center, says the families that cope best with Alzheimer’s and dementia are the ones that manage to change how they define hope and establish new relationships.

“We always look at it long-term,” Waldman says. Instead, families should break it down, hour by hour, day by day.

“If you know the person is still here, you still have an opportunity with this person to have a good day, and that’s your hope,” she says. “You have to change your perspective. ... There are small successes every day.”

For the Patricks, that meant sitting on the couch and holding hands or listening to music.

CHOOSING DIGNITY

When Waldman meets someone with Alzheimer’s or dementia, she looks for the person inside, no matter the stage of the disease.

“I didn’t know who they were, but I know who they are now, and you can see their whole life in their eyes,” she says.

Alzheimer’s takes away roles — mom, wife, daughter, sister — but it does not take away the essence of the person, she says.

“What are the qualities that made your mom a good mom? She still has those qualities,” Waldman says.

Even with Alzheimer’s, Cynthia Valencia‘s mother loved to dole out compliments in the early stages of the disease.

“She was so sweet and so cute and always so friendly,” says Valencia, 45. “So with her dementia, she would want to stop you and talk to you and tell you that your shoes were cute and your eyes were pretty.”

Valencia has been a caregiver for 15 years and started the work six years before her mother, Flossie Walker, was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s. Most recently, she has worked as the community-relations director at Prestige Care Inc. in Green Valley.

The diagnosis frightened Walker, 62, who had cared for her own mother-in-law through dementia.

In November 2012, Valencia’s mother was happy and cheerful, enjoying life in the facility the family selected. By January, she was in hospice, no longer communicating and had limited mobility on the left side of her body, Valencia says.

Even then, Valencia continued to see to it that her mother’s hair was done and her nails painted, giving her the care and dignity she would have done for herself.

Walker died in January 2015 at the age of 71.

“It’s sad because my kids were robbed of the grandma experience,” Valencia says of her two teens and 8-year-old. “But the experience that this gave them, going through this, I think has given them more compassion and understanding for dignity. So when you talk about the upside of it, of course I would like my mom to be swinging on her front porch, drinking lemonade and making cookies, but if something good has to come out of this, I think it’s that my kids have compassionate hearts.”

“YOU ARE STILL YOU”

A new study in “Psychological Science” explores the connection between perceived identity and morality when mental deterioration occurs. Nina Strohminger, a postdoctoral fellow at the Yale School of Management, worked with UA philosophy professor Shaun Nichols to explore how family members perceive the identity of individuals with the neurodegenerative diseases, frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS.

The study found consistency in a person’s moral disposition — not memories, intellect or other characteristics — has the greatest impact on how others interpret the identity of that person.

“We knew that morality would be the most important factor, but we didn’t expect for memory not to matter at all,” Nichols said. The study surveyed people who lived with Alzheimer’s patients.

“The perceived identity doesn’t seem to be affected by loss of memory,” he said.

So even if Alzheimer’s robs other mental functions, the person who maintains continuity in moral character is still more likely to seem like the same person beneath the disease, finds the study, which found Alzheimer’s fell between the two other diseases in how much it impacts perceived identity.

LIVING IN THE MOMENT

Maintaining hope is no easy task when days are long, frustrations run high and grief crushes. Many families instead cling to moments of clarity.

“With my mom, we just lived in every single moment. Whatever her abilities would allow her, that’s what we did,” says Valencia, who has volunteered with the Alzheimer’s Association for three years and is an ambassador to U.S. Rep. Raúl Grijalva’s office.

She remembers holding her mother’s hand, painting her fingernails. Each time her mother tugged her hand away, Valencia chided her. “Mom!” she would cry. Finally, the women locked gazes.

“Cindy!” her mother declared.

“She hadn’t said my name or recognized me in months, so those moments...” Valencia says, emotion choking her voice.

With Alzheimer’s, the present moment together is all there is.

“I love working with people who have cognitive impairments because I think they are the Buddhas on Earth,” says Waldman, of TMC. “They are in the moment. They’re totally here right now.”