Between the Kappa Sigma fraternity house and the bustling Highland underpass on the University of Arizona campus, spiritual seekers of all sorts can find sanctuary and rest.

Here — across the street from the Chi Omega sorority house — you might catch a Buddhist group meditating in the chapel, a graduate student studying in the library or a UA professor eating lunch in the courtyard.

This is the Ada Pierce McCormick Building, or the Little Chapel of All Nations at 1052 N. Highland Ave. Since 1937, the property has hosted deep thinkers and soul searchers.

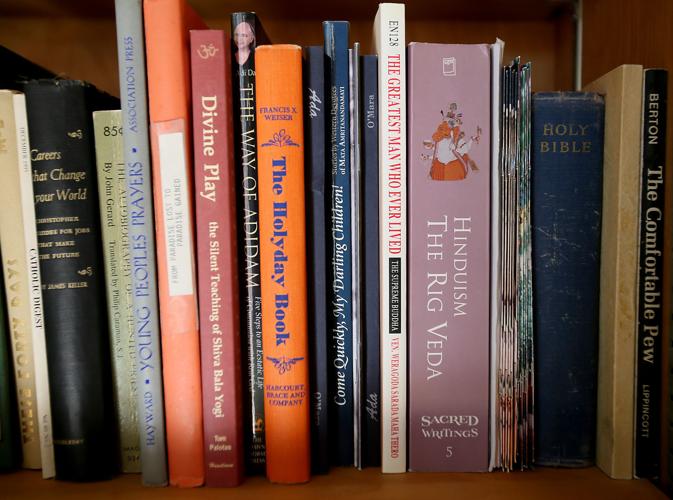

The Little Chapel holds no allegiance to one particular faith tradition. Colorful prayer flags decorated with a host of religious symbols swoop from the chapel’s ceiling, and a simple wooden altar fills the front of the room.

Not many know about the chapel, but those who do need it most, says Randi Kisiel, the executive director of the property, which includes the chapel, a lounge area, a courtyard, a library and offices.

A lifesaver

When Erec Toso, a senior lecturer for the UA’s Writing Program, calls the chapel a lifesaver, he’s not kidding.

Toso discovered the property when he was assigned an office there.

Kisiel remembers that when she first started the job at the chapel in 1996, about a dozen lecturers worked there out of offices rented by the English department. Now, the Southwest Center rents the space.

“It’s a respite from the craziness of academic life and teaching,” Toso says. “It’s quiet, and it’s peaceful, and it’s rejuvenating. It’s a place of reflection and beauty and sacredness and these elements that the university doesn’t have in great supply.”

Even though he now works at the Modern Languages Building on campus, Toso swings by the chapel every day to meditate. This is his home base on campus.

In 2003, after a rattlesnake bit him, the Little Chapel of All Nations helped Toso cope with the pain and exhaustion of his recovery. He returned to work three months after the bite but estimates that it took about four years before his strength fully returned and his body no longer ached.

In Kisiel and secretary Constance Bryden, Toso found empathy. At the chapel, he found a convenient place to park while wheelchair-bound and a spot to retreat when his strength waned during a day of teaching.

“It’s mainly been a place of healing and empathy and a place of acceptance and openness and expression,” he says.

Eighty years

of welcome

The previous executive director, Mary Esther Clark, drilled that message of openness into Kisiel’s head from day one.

Ada Pierce McCormick, the founder, “wanted it to be a place where people could come and pray and meditate, whatever their religion dictates,” Kisiel says.

Eighty years ago, in 1936, McCormick originally purchased property bounded by Speedway and Second Street and Highland and Vine avenues. Over the years, she sold off portions, until all that remained was three houses and a garage, Kisiel says.

For about 10 years, McCormick called the chapel by different names — Cabot Chapel and the Chapel of Wandering Scholars, to name a few.

But in 1946, she appears to have settled on The Little Chapel of All Nations, which was incorporated in 1954, Bryden says.

In 1989, years after McCormick’s death, Clark and the chapel’s board razed the three houses to save costs and continued operating out of the garage until the current building opened in 1990.

“Sometimes I feel bad for never having met her,” Kisiel says about McCormick. “She sounds like a hoot.”

She relays stories passed on to her by her predecessor Clark, who worked with McCormick.

Along with running the chapel, McCormick also started a literary magazine called “The Letter” and was the secretary on the University Religious Council. Kisiel holds that position today.

“The joke was that (McCormick) would go to these meetings and come back and write up these minutes, but she would write the minutes to reflect what the meeting should have been like, instead of how it was,” Kisiel says. “That’s kind of how she was.”

The chapel owes not just its legacy but its future to McCormick — she designated in her will that the bulk of her money would go to the chapel. She died in 1974. That fund, along with donations and rent from the UA, keeps the chapel afloat, Kisiel says.

Respecting differences

In the early years of the chapel’s existence, the Episcopal Campus Ministry got its start. McCormick herself was baptized into the Episcopal Church in her early 20s.

Although that ministry meets at the Campus Christian Center, 715 N. Park Ave., it still returns to the chapel each week for a smaller service.

The Awam Tibetan Buddhist Institute, Water of Life Metropolitan Community Church and Global Chant are a few of the congregations that used the Little Chapel in their early days.

“The setting, the people, everything about it was very nice, but eventually we outgrew it,” says Khenpo Dean Pielstick, the leader of the Awam Tibetan Buddhist Institute.

The library holds around 40 people, and the chapel’s capacity is 25, says Bryden, acknowledging that more may squeeze in depending on room setup.

The property also hosts intimate weddings and memorial services and groups with no religious affiliation. Unless an event runs for more than four hours, the chapel usually doesn’t charge.

“A sex addicts group met here, and the pagans met here,” Kisiel says. She ticks off a few groups that currently make use of the space — The Navigators, a Christian evangelical ministry, a handful of meditation groups and Toastmasters.

“I think more than anything, the Little Chapel does a great job of promoting service to our fellow man,” says Kelly Bauer, the president of the University Religious Council and the director of the Institute of Religion for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. “They always seem to be looking for chances to help the homeless or provide space for classes or international students.”

The diversity of the community makes for interesting conversation. But unlike so much religious rhetoric today, differences are respected. As Bauer puts it, they are “people of faith” without “any horse in the race.”

“It is just a wonderful place for self-exploration and reflection,” says Tana Jay von Isser, a 27-year-old who discovered the chapel when she was a student at the university.

A place of calm

Von Isser’s first experience at the Little Chapel was more startling than soothing.

As a student, training for an on-campus job took her to the building’s library for the first time.

“And I was doing ice breakers with fellow trainees, and I look up on the wall, and I see my great grandmother,” she says. On another wall hangs a portrait of her great grandfather.

The library honors the couple — Murray and Aldine Sinclair — because of their friendship with McCormick. Grandmother Aldine von Isser still sits on the chapel’s board.

“Once the connection was made, I began going over there frequently, almost every day I was on campus,” she says, calling it “a place of respite in a beehive of chaos.”

The chapel gave her a place to breathe and meditate.

“You can’t go through college and not have some hard stuff come up,” she says.

When she was academically disqualified for her fourth semester, she found encouragement at the chapel to continue her education.

And when her father died, the denizens of the Little Chapel rallied around her.

“They offered open ears and compassion and love,” von Isser says.

And that’s what keeps von Isser and other regulars coming back.

“There is no way you could overstate how wonderfully humble and present and nourishing and powerful it is,” Toso says. “It’s like homespun soup in the middle of a crazy banquet.”