La Placita’s past will be part of its future.

The multi-colored complex on the grounds of the Tucson Convention Center is a pile of rubble now. What will rise up will be an apartment complex bearing the name of a business and family that once thrived there.

HSL Properties began demolition on the village in January. In its place they are building “The Flin,” a market-value apartment complex named after El Charro Café’s Flin family. Omar Mireles, president of HSL, says the historical buildings including the Samaniego House, the stables and the Flin building will be preserved.

They provide echoes of an area that was once teeming with life before homes and businesses were razed in 1971 for the Convention Center and office complex.

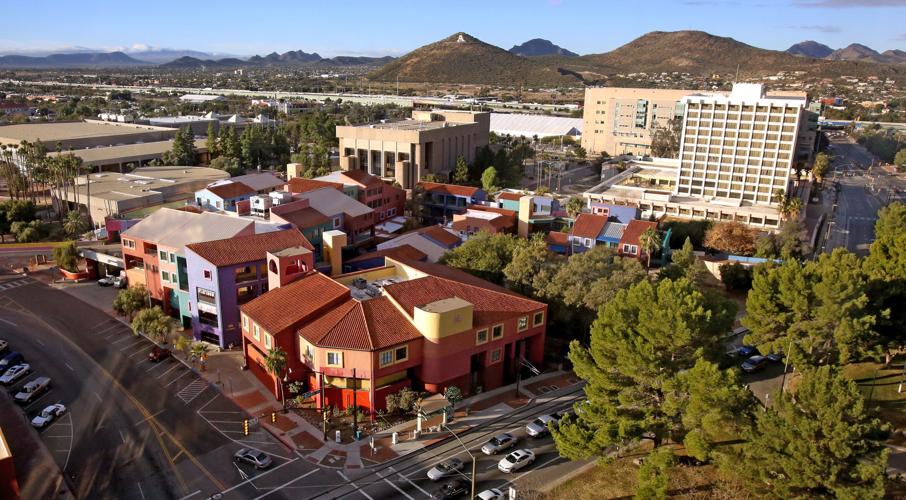

La Placita Village, recently demolished, was a colorful, mixed-use, multi-storied building complex with office and retail space downtown at West Broadway and South Church Avenue.

Once, Mariachi music poured out of La Placita every weekend as locals gathered to dance and socialize with their neighbors. Children dressed in traditional Mexican and Spanish costumes paraded through the placita kicking off festivities for La Placita festival, which began in 1950.

La Placita had a little bit of everything. Locals with a sweet tooth visited Ronquillo’s Bakery before heading to La Plaza Theatre for a Spanish movie. El Charro Café, the home of the chimichanga, provided patrons a taste of Monica Flin’s famous Sonoran food.

Carlotta Flores, El Charro Café chef and Flin’s great grandniece, remembers visiting El Charro with her grandmother before heading to the cine.

El Charro “had a couple small apartments where some family or employees would live on and off as needed,” she says. “It was a mini community in and of itself.”

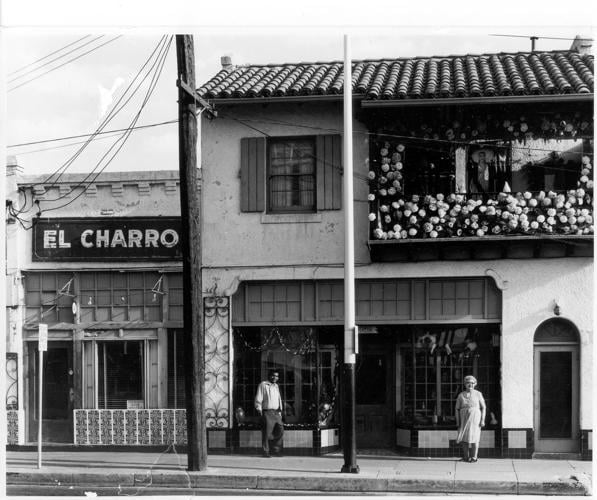

El Charro Café owner Monica Flin and her nephew Steve Flin stand outside the café before it was razed to make way for the Tucson Convention Center. After it was demolished, El Charro moved to its present location on Court Avenue.

El Charro Café was just one of many businesses and families evicted from La Placita by the City of Tucson’s urban renewal plan, forcing the Flin family to move to their present location on Court Avenue and flattening homes of families who had long lived there. La Placita Village, a multimillion-dollar commercial complex meant to complement the new community center, took its place.

“It was devastating,” Ray Flores Jr., Carlotta’s son and CEO of Flores Concepts, says. “Monica was quite old when this happened, and the stress and turmoil it put on her basically stripped her of her ability to start all over. Luckily, Carlotta was filled with enough spirit and gumption that she was able to pick up the pieces and carry on the tradition.”

One day before the urban renewal began, Alva Torres, who frequented the Placita, was at a party when she noticed Rodolfo Soto in distress. Related by marriage, she approached Soto and asked what was wrong.

“Oh, Alvita, you know that they’re tearing down the Placita, and they’re going to forget we’re even here,” Soto told her.

“When he said that, I thought I had to do something,” Torres says.

Torres started a prayer group that turned into the La Placita Committee, which fought to save the historical Placita. Despite their efforts, the Placita was demolished. Only the gazebo, kiosk and a few historical buildings were preserved.

The realignment of Broadway is shown in this illustration from the mid-1960s. Among the demolished: (1) Tucson Army Surplus, (2) Plaza Theatre, (3) Ronquillo’s Bakery, (4) La Placita Park, (5) Greyhound Bus station, (6) El Charro, (7) Belmont Hotel, (8) Myerson Building.

Lydia Otero says La Placita Village’s purpose was to attract tourists and suburbanites, but it never truly served its commercial function, remaining vacant for many years. Otero, an associate professor of Mexican American Studies at the University of Arizona, wrote “La Calle: Spatial Conflicts and Urban Renewal in a Southwest City,” a book about Torres and the razing of the neighborhood.

After meeting with community members, HSL’s Mireles realized the importance of illustrating the vibrant community that lived in the area.

“The plan is to provide a pictorial history with descriptive narratives developed in collaboration with Los Descendientes del Presidio de Tucson, Professor Lydia Otero and the Arizona Historical Society,” Mireles says. “We hope to achieve this through public mosaics, murals and public art exhibitions by local artists.”

“You can build on an area’s history and culture, and you can market it,” Otero says. “So he’s looking at it in a way that other developers are not.” She views the untapped history as a resource La Placita Village was lacking. “We want visitors to know the history of the area because I think that tourists want a more authentic experience, and it would be to his advantage, to HSL Properties, to invest a little bit in the Tucson history of that area.”

The Flores family says the homage to its family was a surprise. They are thrilled with this news and plan on attending the unveiling.

Annie Morales Lopez, president of Los Descendientes del Presidio de Tucson, says once the design plans are finalized they will look into how to structure the public art and historical installments.

“We were born here so it has to be something historical to try to preserve Tucson because everything is always being knocked down,” Lopez says.

This is a scan of a water-damaged photo negative that shows La Placita Park on West Congress in Tucson in 1954. In the background is the Belmont Hotel at left, El Charro Mexican Restaurant and Frank’s Billiard Hall. At far right is “A” Mountain.

Torres remembers the feeling of the original Placita, moving her to tears.

“It always had a good atmosphere and put together it was like representing all kinds of people, all races, all ages, so that was what was nice, and it doesn’t do that anymore,” Torres says. “You could go there, and to me it was like magic.”

Torres would like to see commemoration of the original structures through historical photos and murals. She says she’d love to see the original Placita spirit revived.

“Maybe they could invite different schools to come play once a week,” she says. “That kind of a feeling is just as important as the building. So I have hopes that Omar wants to see into some of this.”

The Flin apartment complex is slated for completion in Spring of 2020. Mireles says the Samaniego House will likely become a restaurant, and portions of the Flin building will become a coffee shop and other related retail spaces. The rest of the portions of the Flin building and the stables will be used as living amenities to the apartment residents.