If you ask elders from Tucson’s Chicano/Mexican American barrios if they remember Ernesto V. Portillo, you are likely to hear an enthusiastic, “Oh, yes,” in Spanish. “I used to hear him on KXEW, Radio Fiesta,” they might add in English. Or they might also say, “He had such a beautiful voice and played wonderful music.” And others might remember the interviews, “Charlas Portillo,” he conducted on Saturday mornings, during which listeners would learn about important community news and information and events.

Even younger Tucsonenses, whether they live in Tucson or somewhere else, will remember and proudly proclaim, “Yeah, my grandparents and parents would always listen to Mr. Portillo on the radio. That’s where I learned to love musica mexicana, music that would bring smiles to my padres and abuelos.”

On Sunday, Nov. 2, before dawn broke on Día de los Muertos, the voice of our dad went silent. He made his transition in his Armory Park home, surrounded by our mother, Julieta Bustamante Portillo, daughter Carmen J. Portillo, sons Mario A. Portillo, Carlos R. Portillo, and me. He had celebrated his 92nd birthday on Oct. 21.

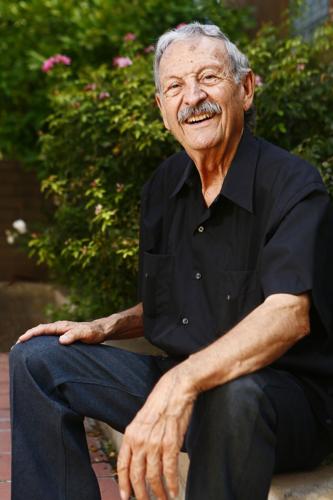

Ernesto Portillo: “He had such a beautiful voice and played wonderful music.”

For 50 years, Ernesto V. Portillo’s elegant voice could be heard in Spanish (and sometimes in English) over Tucson’s airwaves, beginning with KEVT-AM, Tucson’s first Spanish-language radio station, then KXEW-AM & FM, and finally with KQTL-AM. His words, his musical selections, his pensamientos, brought comfort to his listeners and acknowledgment to their lives. But more than sharing the grand music of México — Javier Solís, Lucha Villa, Lola Beltrán, Pedro Infante, los trios y los mariachis — he opened the airwaves to the barrios of his beloved adopted community of Tucson.

When our father, who was 20 years old and had $60 in his wallet, left his home and family in Cd. Juarez, Chihuahua, México, and traveled by bus to Tucson, in early spring of 1954, he arrived not knowing a soul or anything about Tucson. The only place he knew outside the border was Kansas City, where he spent a summer living with his eldest sister and working as a fancy hotel busboy without papers.

The day he arrived at the old Greyhound bus station downtown, which was located where the statue of Pancho Villa proudly stands today in Veinte de Agosto Park, he auditioned for an announcer’s slot at KEVT, which had begun broadcasting six months earlier. Within minutes, he would recall, he was hired and that day, March 4, he began his career in radio and his road to celebrating his community, its culture and contributions.

Ernesto V. Portillo talks to Margarita Robles in the KXEW radio studios in Tucson in March 1980.

Instantaneously, the proud familias mexicanas welcomed his warmth, his charm, his radio demeanor. Tucson’s barrios, whose histories stretched back to nearly 200 years, had few public personalities whom they could admire and cherish and call their own. In turn, he embraced the people who brought him into their homes, lives, traditions. He and his listeners shared their love of the borderlands’ rich history and culture. He also immediately became enchanted with our intoxicating desert air and landscape, our majestic mountains, and highly anticipated healing summer chubascos.

He fell in love with his to-be-explored town, its people and made Tucson his home.

Ernesto Portillo’s mission had a message: Tucson’s Mexican American community’s long, critical history cannot be ignored.

In the ensuing years, he would grow as a husband, a father, a son, a brother, a community partner and a Tucsonense. Within two years of his arrival, he enlisted in the Arizona National Guard and remained with his Army buddies for seven years, leaving as a staff sergeant. He was forever proud of his service to his country.

As his radio personality evolved, he came into his own as the barrio’s town crier — through KXEW’s airwaves and other community communication initiatives. He opened the radio station to activists, teachers, students, labor leaders, including César Chávez and Dolores Huerta, politicians, padres de familias. Before the advent of Spanish-language television and decades before the modern trappings of blogging and social media, Don Ernesto Portillo transformed KXEW into a must-listen-to megaphone of local and national social and political changes.

His mission had a message: Tucson’s Mexican American community’s long, critical history cannot be ignored.

One of his biggest but unknown impacts was making space for bilingual, barrio savvy psychologists to talk to listeners about the importance of mental health and to erase the taboo of discussing openly the subject. As a member of the board of La Frontera Center, a pioneering mental health clinic, headed by Dr. Nelba Chávez, he helped establish a major Tucson institution — La Frontera’s Tucson International Mariachi Conference.

Years earlier, he had been instrumental, along with former City Manager Joel Valdez, in elevating Los Changuitos Feos de Tucson, which was born in 1964 as the first permanent mariachi youth group in the United States.

Ernesto V. Portillo poses for a portrait in the backyard of his home in Tucson in 2015.

In subsequent years, he joined Alberto M. Elías to create a Spanish-language newspaper, La Voz del Pueblo. He also teamed up with Mr. Elías and others, including stage director Barclay Goldsmith, to bring Spanish-language theater to Tucson. Goldsmith would later serve as the midwife to trailblazing Teatro Libertad, the predecessor to the present Borderlands Theater.

As the Chicano rights movement began to flower in Tucson in the late 1960s, young community leaders — the late Congressman Raúl Grijalva, Salomón Baldenegro, the late writer Silviana Wood, Guadalupe Castillo, Isabel Garcia and others — demanded accountability from the City of Tucson to stop ignoring the barrios and to provide better services to la gente. My father allowed the young activists to take their fight to the airwaves. And in 1975, in an unprecedented action in Tucson when the federal government invaded and seized the files of the clients of the Manzo Area Council, an immigration rights’ organization on the west side, again my father opened the airwaves of communication to its leaders to inform the community of the government’s provocative action and damaging consequences.

Ernesto V. Portillo Sr.

He was one of the few visible Tucson leaders who paid attention to and gave space to the women activists who lead Manzo Area Council. And there were many other community organizations, social, political, and educational, which received the same respect and lent their voices on the radio.

While our father grew up in the relatively conservative rural area of southern Chihuahua, and in the post-War II borderlands, he was conscientious of the changing social winds and was unafraid to challenge his own beliefs.

This is what I believe to be our father’s legacy: He understood the crucial role of the radio, the power to communicate the accomplishments and struggles of the residents of the barrios. He understood that the radio station was the people’s radio station.

His message was his mission.