BOWIE — Farmers from California and Arizona are pushing to drill wells and pump unregulated water in Cochise County, triggering intense rivalries and calls for a crackdown.

Some farmers from the drought-parched, increasingly regulated Central Valley of California want to plant pistachios and other crops here, largely to feed China’s growing demand for tree nuts. But others who are already here and pumping water want the state to limit new irrigation.

The conflict erupted recently at an emotionally charged public hearing in the Bowie High School gymnasium. Hundreds of people argued for the right to keep drilling and irrigating — among them aspiring farmers, existing ranchers and growers who plan to expand, and retirees and other landowners who hope to sell for cropland and don’t want their future access to the water shut off. They drowned out comments from a handful on the other side who say they’re trying to protect the aquifer.

“Our concern is the future, about wanting to grow as a family, as an operation,” says Geneal Chima, who has moved his farming operations from California’s Central Valley to this far southeast corner of Arizona and opposes new regulation.

Prominent pecan grower Dick Walden, a native Arizonan who has groves in nearby San Simon as president of Farmers Investment Co., counters: “Ultimately, if we don’t have some kind of regulation, we’ll run out of water” that can be pumped affordably.

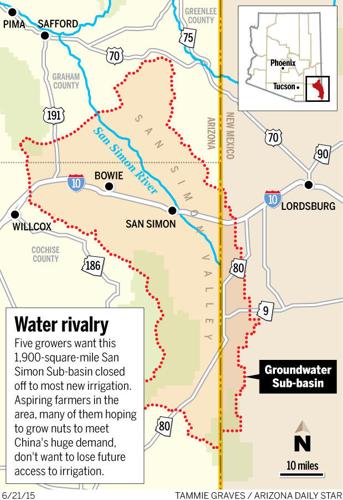

Five big growers, including Walden, have petitioned the state to close off a 1,900-square-mile area to most new irrigation. They’ve gotten state water regulators to temporarily halt most watering of new farmlands, but the long-term outcome is far from decided.

Lure of less regulation

Chima and Barton Heuler are California transplants who sit on opposite sides of the issue. They both moved their farming operations here because they were tired of seeing water poorly managed and transferred away from crops because of drought. Chima says he was tired of excessive regulation in his former state.

Heuler, owner of A&P Ranch, a nonprofit growers cooperative, shifted his farming operations from Kern County, California, to Bowie after selling thousands of acres of pistachio groves in that state’s Central Valley. He bought out another pistachio company here in the 2000s, and expects his new orchards will take a decade to reach full production.

He grows 4,000 acres of pistachio trees here. Companies he has ties to have filed five of the 28 notices filed with the state in the past year to drill large-volume wells. He would not speak in detail with the Star, but in a 2010 interview with a farmers’ credit company publication, he said he plans to double Arizona’s total output of pistachios and hopes his groves last 100 years.

Chima, of Silverado Farms, said he sold his Yuba City, California, farm at the first of the year. At various times he had grown wheat, rice, fruit, alfalfa and nuts there since 1970. He has bought 900 acres here so far and has a contract pending to buy 300 more. He’s turning his land a few miles south of Interstate 10 into a pistachio orchard and says it has a long enough irrigation history that he believes it would be grandfathered even if most new irrigation is banned. He and his wife have had the land cleared, had electric lines installed and had pumps and wells reconditioned.

He has filed seven well-drilling notices. Another Californian, Sam Weis, has filed two. Twenty others have come from prospective drillers in Phoenix, Cave Creek, Carefree, San Simon, Safford and Bowie.

Chima’s wife, Lisa Chima, says she believes there is no water shortage in the area, but that large growers have been buying up land, making sure it’s irrigated, and then declaring a water problem.

Not true, Heuler said. While the aquifer is stable today, he said it will collapse if pumping expands without controls. He draws a contrast between himself, his fellow petitioners and other farmers: “When we plant, we’ll plant half the acres we buy, and leave the rest fallow.” Other growers plant “from fencepost to fencepost,” he said.

The state doesn’t regulate water use in mostly rural Cochise County, so landowners today can pump with no limits.

Monopoly in making?

That’s in sharp contrast to Pima and Maricopa counties, which have had broad pumping controls since passage of the Arizona Groundwater Management Act in 1980. The limits on new irrigation sought for the San Simon area are already in effect in the urban counties.

The big growers want a large area known as the San Simon Vally Sub-basin declared an irrigation non-expansion area. If they prevail, crops could be planted only on land irrigated in the previous five years or on parcels of two acres or smaller. Crops also could be planted on land owned by people who made “substantial capital investment” on the lands.

To opponents of the proposed irrigation limits, the growers pushing for them are “tree barons,” trying to monopolize farming.

Critics say the limits would violate constitutionally guaranteed private property rights, although the Arizona Department of Water Resources considers groundwater a public resource, not private property. They fear it would render their land worthless, wrecking investments they’d hope to farm or sell for retirement income.

Most of all, they are angry that their larger adversaries have bought up land, drilled wells and built large farms over the past few years — and now want to shut out competitors.

Actually, current levels of pumping could continue indefinitely without serious harm, opponents of the limits say.

A U.S. Geological Survey study years ago found that the aquifer contains 25 million acre feet of water down to 1,200 feet deep. In the past few years, well levels have dropped at an average of 1.2 feet a year, which they say means the water supply could last hundreds of years.

Proponents of the limits on new irrigation note that wells directly under existing farmlands are dropping much more rapidly. But they see an influx of future farmers as the bigger problem.

On Wednesday, the state released a computer model which predicts that, at current pumping rates, the water table would drop by 2115 to a maximum of 615 feet in the Bowie area and 441 feet in the San Simon area.

If it keeps dropping at the current rate, it will become too expensive to pump any deeper, Walden said. His company has been growing pecans in Sahuarita since the 1940s.

Ranching vs. farming

Heuler, Walden and their allies control well over 10,000 of the 20,000 acres now being farmed here.

At least 10,000 more acres of potential farmland is owned by opponents of the limits on new irrigation. And even more land could be bought and irrigated.

Benson real estate agent Cheryl Glenn said she has sold land to 10 different families — some local, some from out of state — who bought in hopes of building a farm.

Her website lists seven parcels for sale here, ranging from $1.14 million for 1,100 acres to $39,900 for 40 acres.

“There are two industries in this market — farming and ranching,” she said. “To ranch, it takes a great deal of acres because you can run only 14 head of cattle per section. People can buy 40 to 80 acres and farm.”

Mark Cook, a Willcox native who also signed the petition to limit new irrigators, recently drove his pickup truck up a dirt road south of Bowie to make the point that growers are arriving fast. He passed 640 acres that had recently been cleared by one grower and 160 acres where a second grower planted pistachio trees shortly before the state froze new irrigation.

Then, he drove up a stretch of road that he said had been graded for the first time two weeks ago.

“This is not simply a matter of California versus Arizona farmers — this is a matter of international financial entities looking for good investments,” said UA law professor Robert Glennon, author of two books on water. “You’re seeing a lot of foreign money coming into the U.S. searching for places to invest, and one place they’re investing in is agricultural land.”

Pecan grower Walden decided in the winter to push for the petition to limit new irrigation, saying he noticed “an awful lot of outsiders coming here and buying ranchland.”

“We know water is a finite resource. Farmers Investment has lived with a regulated water supply here in the Tucson management area for many years,” said Walden, although his company has drawn repeated criticism for its pumping.

Walden bristles at accusations that he’s seeking a monopoly. His company has made a big investment in the area and employs 23 people here, he said. He’s simply trying to prevent “uncontrolled expansion,” he said.

But at his home more than 10 miles of dirt roads south of San Simon, Shelby Ray said his family sold 240 acres to Heuler’s A&P company about five years ago, and he wishes he hadn’t. He and his wife still have 320 acres of farmland they would like to sell, but the proposed limits on new irrigation would stop that, making the land worthless, he said.

Dennis Krache of the San Simon area testified in May that he stopped farming 170 acres of alfalfa and other pasture crops about a decade ago, when his wife fell ill. Now an 88-year-old widower, he’d like to sell and return to Hawaii, where he lived until 1979. But if the petitioners prevail, he said, he won’t be able to do that.

Demand for nuts sparks revival

Farming boomed in this area from the 1940s to 1985, and the water table dropped an average of 2.2 feet a year as 145,000 acre-feet per year went to farmland, mostly cotton fields.

“Bowie was one of the prettiest towns in this state back in the ’50s and ’60s,” recalled rancher Ray. “We had a very elite group of farmers, and most had money. We had a theater, drugstores, all kinds of filling stations and motels, grocery stores and hardware stores.”

That all changed when Interstate 10 bypassed the communities in the ’60s and ’70s, and then farm prices crashed and energy prices spiked in the early 1980s. By 1991 only 12,000 acres were planted and the water table’s decline slowed to 0.7 feet a year by 2007.

Since then, production has risen to about 20,000 acres as global demand for pistachios and pecans triggered a shift away from cotton and alfalfa. China now buys 30 percent of all pistachios and pecans grown worldwide, farmer Cook said. Walden said 50 percent of his pecans are exported.

As acreage has nearly doubled, so has the rate of decline in the water table, state figures show, and it’s likely to accelerate if more farmers start drilling. That’s why the limits on new farming are needed, the petitioners say.

Cook, for one, said he feels so strongly that he’s not about to give up in the face of opposition. If the state decides against limiting new irrigation and the growth in farming continues, he said, “I’ll be back in two years” to petition again.

But new limits are unnecessary, opponents say — the state already requires proof that pumping levels are sustainable over the long term before allowing new irrigation. They argue that making changes based on fears of the future would benefit only the large growers petitioning for the change.

At the May hearing, Phoenix attorney Lee Storey, representing opponents of the proposed limits, used a Monopoly metaphor to make her point. If the petition succeeds, she told the crowd, “The petitioners will be living on Boardwalk and Park Place, pass Go and collect $200. The rest of us will be living on Baltic and Mediterranean avenues.”