It was 1963, likely in the summer, when Felicia Frontain, her sister Michel and their father Dick Frontain drove a friend of her dad’s to the Tucson airport. Before the friend boarded the plane, he knelt on the runway between the two standing girls.

The man, wearing dark glasses and with his right hand bandaged, smiled brightly, as did the girls. Dick Frontain snapped a photo. Felicia was 5 and her sister was 2.

“We had to call him Mr. Moreno,” Felicia recalled. “Our parents were big on protocol.”

Mr. Moreno was Mario Moreno, better known to millions of his adoring fans as “Cantinflas,” the Mexican comic and film star.

It’s a memorable photo that Felicia cherishes, not so much because she and her sister were photographed with the legendary Cantinflas, though that’s more than enough among Cantinflas fans, but more so because the photo reminds her of her father and represents all that he accomplished. It’s a photo that captures a minute in time of a different Tucson, foreign from the one we know today.

Dick Frontain, who was born in New York, came with his wife, Mona, to the desert in 1956 to attend the university. He taught English, drama, journalism and writing at Marana High School and later Pima Community College.

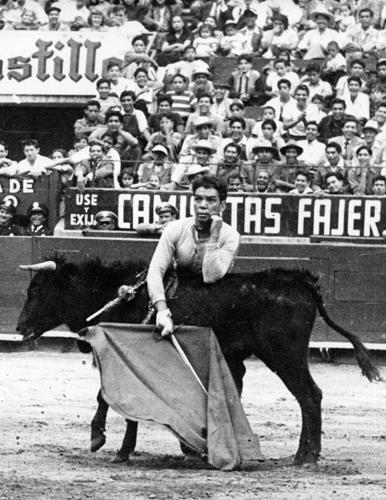

But to many in Tucson and beyond he was known as one of the premiere writers north of the border specializing in bullfighting. He wrote about the grace, drama and gore of the sport for the Arizona Daily Star and other publications, and he befriended many of the world’s best matadores from México and Spain.

He also was good with a camera. He extensively photographed bullfights, Tucson’s Yaqui communities, and his friend and neighbor, artist Ted De Grazia. He and De Grazia collaborated on a 1967 book, a homage to bullfighting, “Mexico’s Border Bullrings.”

Felicia said that her father, who died in 2007, donated three boxes of negatives, hundreds at least, of his three favorite Southwestern subjects to the Arizona Historical Society.

But one photo that is not in the society’s archives began to develop one day when Dick Frontain told his girls, “We’re going to have fun.”

They got into their parents’ station wagon. Felicia’s late mother was probably at work at the University of Arizona’s music library and her younger sister, Maria, probably stayed with the sitter, said Felicia, the undergrad internship coordinator at the UA’s Norton School of Retailing and Consumer Sciences.

The trio went downtown to pick up Cantinflas, maybe either at the Pioneer or Santa Rita, the two better appointed hotels of the day. The girls hadn’t met him before but they knew who Cantinflas was.

“He was a big deal,” Felicia said in an understatement.

More than a big deal, Cantinflas was one of the world’s best known personalities. The comic genius made about 50 films from the 1940s through the 1960s. Many of them were shown at the old downtown El Cine Plaza, Tucson’s Spanish-language movie house that was demolished for urban renewal. To American moviegoers he was known for his role in the 1956 film “Around the World in 80 Days.” His arcane, rapid-fire speaking became known as “cantinflear” and is enshrined by Royal Spanish Academy, the guardians of the Spanish language.

But to the Frontain girls, he simply was their dad’s friend. “I remember he was super, super polite,” Felicia said.

Cantinflas had performed in the Nogales bullring. He was a respected amateur bullfighter where he took on the novillos, the young bulls. Cantinflas didn’t kill the bulls but just toyed with them with his capote de brega, the cape that the matador displays with graceful passes in the early stage of the corrida de toros.

But he did it his way. His bullring clownish antics had his fans in stitches.

“He made a whole comedy routine of it,” she said. “He was phenomenal.”

And when Cantinflas had his picture taken with the Frontain girls, he had them in stitches, too, Felicia remembered.

She recalled other famous toreros who came to Nogales and Tucson, many of whom stayed with the Frontain family in the guest room in a big house the family rented on North Sixth Avenue, south of Speedway. The matadors came to Tucson to shop or see a doctor when they were injured in the bullring, Felicia said.

For Felicia and her sisters, the matadores were their friends who would entertain the girls in pretend bullfights. The visitors would also offer tips on using the capote and muletas to Dick Frontain, who was known to get into an occasional real bullring.

“We just grew up with them,” Felicia said of the visiting bullfighters whom she would see in the Nogales ring.

Thanks to her dad.