Pima County is gearing up to place signage at some busy intersections in an effort to dissuade panhandling.

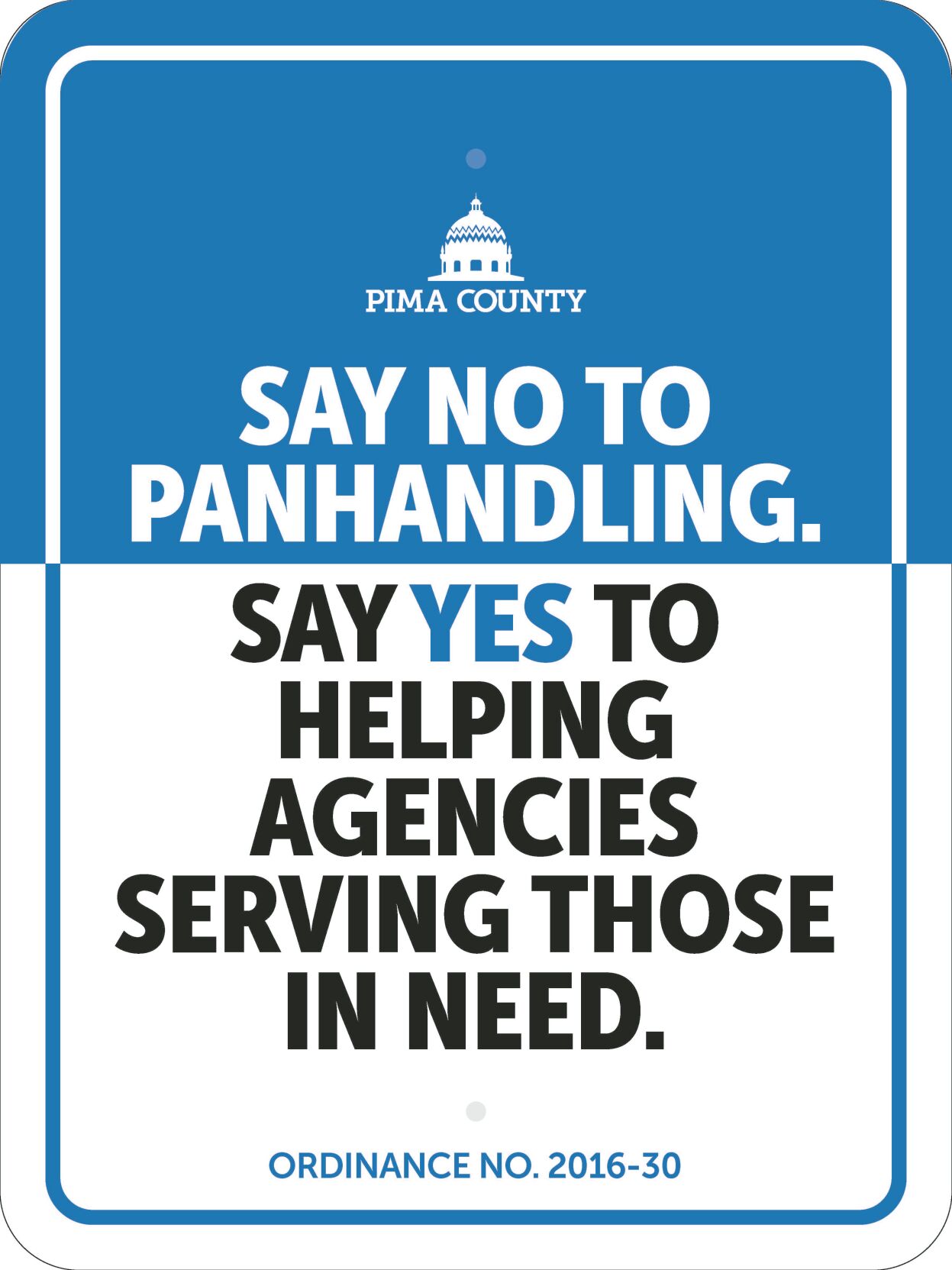

The signs will read: “Say no to panhandling. Say yes to helping agencies serving those in need.”

The move comes from the recommendation of the county’s Small Business Commission, which advises the Board of Supervisors on policies that affect the local business community, County Administrator Jan Lesher said.

The county has yet to establish a timeline for the Transportation Department to begin placing the signs, but they’re set to go in the same 32 signalized intersections where “no trespassing” stickers were placed in 2016 after the board passed an anti-panhandling ordinance.

Ordinance 2016-30 prohibits pedestrians “from occupying medians on County highways except as temporary refuge when crossing a highway.” Violations don’t arise from the act of soliciting money itself, but from trespassing when remaining on the median for too long.

Pima County is planning to place anti-panhandling signs at well-frequented intersections in incorporated county limits.

Only 22 citations have been issued for violating ordinance 2016-30 since 2016, according to the Pima County Sheriff’s Department. Violations are punishable by a fine of $140.

While pedestrians can wait at a median when crossing the street, legal violations arise when people remain at medians for several light cycles.

Deputy Tyler Legg, the public information officer for the Sheriff’s Department, said during his time in patrol calls for panhandling were “fairly common,” but that “the approach that was normally taken was to educate” instead of to cite individuals.

Even though panhandling extends far beyond unincorporated county limits, the county can only enforce its own ordinances where it has jurisdiction. Tucson has its own laws against “aggressive solicitation,” but City Attorney Mike Rankin said panhandling itself is constitutionally protected under the First Amendment.

Get your morning recap of today's local news and read the full stories here: tucne.ws/morning

“What is not protected is behavior that threatens public safety, or that is otherwise illegal for reasons that are not related to the content of the person’s speech,” Rankin said in an email. That includes when “the person follows someone after a refused request for money, or shouts at them, threatens them, makes physical contact, blocks their way.”

Josh Jacobsen, a member of the county’s Small Business Commission and steering leader of the Tucson Crime Free Coalition, a new group advocating for a tough-on-crime stance to addressing the region’s homelessness crisis, said he pushed for the county’s new panhandling signs.

Jacobsen described the signage as an “incremental win for the community,” and a way “to start to educate the public on the danger that fentanyl plays in our community.”

“If you’re giving somebody that’s on the median a $20 bill, you very likely just bought them roughly 20 fentanyl pills. And that just perpetuates the cycle of substance abuse that people are stuck in,” he said.

Tucson Police Department Chief of Police Chad Kasmar has expressed how the proliferation of fentanyl in Tucson affects the unsheltered population, as the highly addictive substance can be obtained for as little as $2-3 a pill.

“Narcotics, fentanyl, opiates and methamphetamine are a contributing factor to many of the issues that we face in our community, and is certainly contributing to the expansion of our mental health issues that we have in our unsheltered population,” Kasmar told Tucson City Council at its Jan. 24 meeting, adding that 271 fentanyl-related overdoses occurred in Pima County last year.

However, it’s unclear how those who panhandle spend the money given to them.

Anti-panhandling signs “seem to be used in many cities now, but (I’m) not certain that it reduces panhandling,” said Tom Litwicki, the CEO of Old Pueblo Community Services, a nonprofit with the mission to end homelessness in Pima County.

“Our experience with persons who are living on the streets points to most persons using money for food and then other needs, such as alcohol and drugs for those with addiction or alcoholism. I’m sure there is a wide range in how people use the money,” he said.

The new signage from the county will instead encourage individuals to donate to local nonprofit organizations like Old Pueblo Community Services that help the homeless population by providing shelter and other basic necessities.

Lesher said there’s no enforcement planned to deter panhandling, but hopes the signage spreads the message that “if you feel badly, if you want to give money, perhaps think about giving it to a nonprofit that can help the folks rather than the individual directly.”

Aerial photos of Tucson, Pima County, in 1980

Swan Road and Sunrise Drive in February, 1980. The new Safeway Plaza is bottom right. Catty-corner from the Safeway, a Burger King restaurant is under construction. Across the street, land bladed for a Valley National Bank (now Chase Bank), a restaurant, retail and apartments. The old Rural Metro fire station is behind the street mall at top right.

Oracle Road (left to right) and Ina Road in February, 1980. There were gas stations on three corners of the intersection. All have been demolished. The venerable Casas Adobes Plaza is lower right, now anchored by Whole Foods. The open land at upper right is now the Safeway Plaza. The bank on the corner is still there, but the existing buildings to the right were demolished to make way for parking for the new plaza. Lower left is the property for the Haunted Bookshop, now Tohono Chul Park.

Oracle Road and Magee Road north of Tucson in February, 1980. Plaza Escondida is at right, now anchored by Trader Joe's. The open land at bottom of the photos is now the large retail plaza anchored by Kohl's, Sprouts and Summit Hut. The Circle K (sitting alone, upper left) is now a ballroom dance studio. Note the new asphalt on Oracle Road. In 1977, the state approved a project to widen Oracle Road (a state highway) to six lanes from Ina to Calle Concordia. That may be the last time the road was paved.

Tucson Medical Center in February, 1980. The intersection of Grant and Craycroft roads is at bottom left.

O'Reilly Chevrolet (cluster of cars), then Park Mall (center left) and Broadway Road in February, 1980. The open land at top left is now Williams Centre.

The FICO pecan orchards, bisected by South Nogales Highway, looking north to Sahuarita Road in February, 1980.

Tanque Verde Road (bottom left to upper left) and Wrightstown Road in February, 1980, before the City of Tucson constructed the grade-separated interchange. The first units of the Tanque Verde Apartments are lower left. The Circle K facing Wrightstown at the intersection is now Pair-A-Dice Barbers. The large parking lot and building to the left of the Circle K was the O.K. Corral Steakhouse, which was established in 1968. It closed in 2008. It's now Borderlands Trading Company.

Corona de Tucson Baptist Church, lower right, on Houghton Road south of Sahuarita Road in February, 1980. With exception of some infill housing and a few more trees, the neighborhood looks pretty much the same.

IBM (International Business Machines) on south Rita Road, looking north to the Santa Catalina Mountains in February, 1980. In 1988, IBM began phasing out data storage products manufacturing in Tucson, resulting in the loss of nearly 2,800 workers in Tucson, part of a $600 million consolidation plan.

Tucson National Golf Course north of Tucson, looking south, in February, 1980. The Cañada del Oro Wash is at left. Magee Road goes left to right at the top of the photo. Shannon Road curves to the left at top of the photo. That open land is now home to Pima Community College and the YMCA.