Mine tales: There's gold, silver and copper in those Arizona hills

- Updated

Here are 15 stories detailing Arizona's mineral riches that have been and are being mined.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

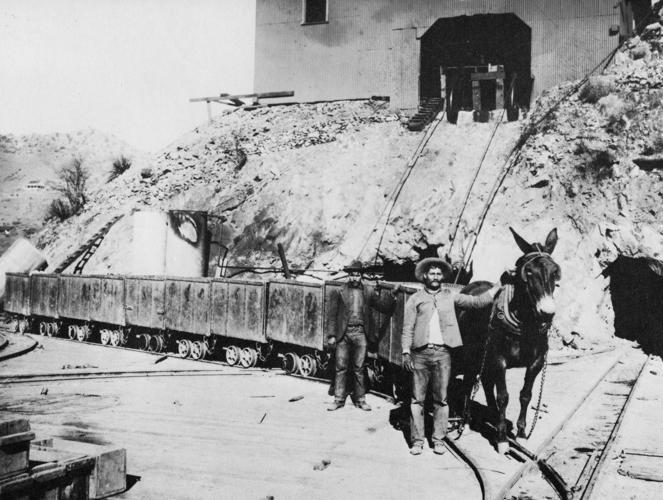

Ore-hauling animals contributed economic savings and production to many of Arizona’s mining towns and camps of the past.

The expense of underground transportation constitutes a considerable percentage of the total mining cost in most mines, exceeding at times the expenditure of stoping (opening large underground rooms by removing ore), the Bureau of Mines has observed.

In the early years of underground mining in Arizona, miners known as trammers were responsible for pushing ore-laden carts. As mines became more developed, in excess of 500 feet, this operation became less efficient.

Mining companies found a solution, using animals to improve efficiency and economy for long-distance hauling.

Mules, draft horses, burros and oxen were traditionally credited with having participated in overland ore transport. Also supplying the power for hoisting material to the surface, they were later replaced by steam engines using steam from a boiler assembly.

Mule teams transported copper bars from the mines at Clifton-Morenci 1,200 miles to Kansas City, the closest railhead and access to markets.

Local transportation in mining towns also relied upon animal s. The Detroit Copper company store at Morenci offered the option to residents of home delivery for grocery supplies by burro or mule. Burros could also be seen transporting water in two canvas bags holding 40 gallons. The average cost was 50 cents a load.

Oxen were the beasts of choice for freighting ore from the mines in Bisbee and Morenci.

Mules have historically been the preferred animal for transport, weighing between 800 to 1,200 pounds. Mules are smaller than draft horses, require less headroom, have the ability to endure heat and are more robust when compared to the horses. They are less likely to become lame.

Unlike horses, which are prone to smash their heads against a low-lying underground drift, a mule would duck its head to avoid such a collision.

The cost of procuring good mules for mining operations ranged between $150 to $300, taking into account their condition, age and weight. Mules were expected to work underground between three to seven years. Afterward, they were retired, being brought to the surface at night and slowly re-exposed to daylight by being kept in a dark room lit by candlelight with increments of exposed daylight over the course of several weeks. Then, they were set free to run wild.

Mining operations at Bisbee relied upon mule haulage or tramming beginning in 1907, continuing through 1931. Earlier operations relied upon the miners themselves to move the ore cars by hand.

Obvious limitations arose, since miners could only tram a single loaded car in contrast to mules, which could move five or more cars. The cars weighed 800 pounds empty and around 2,800 pounds full. Mules possessed enough acumen to realize their limitations. When miners attempted to add extra cars , the mules chose not to move until the additional weight was removed.

Mules and horses working underground on average traveled 3 to 15 miles per shift.

A mule school existed at Bisbee on a hillside above Brewery Gulch to train young mules for underground mining. The school was composed of a circular track, one switch and 30 feet of straight track on a flat surface of the hill. Working without bridles or reins, mules were given their daily lessons of waiting at ore chutes until cars were loaded and directing cars by kicking switch points along the track with their hooves. They became proficient at gathering ore-laden cars from the loading faces to a siding on the main haulage way, afterward returning the empty carts.

They also quickly learned to follow voice commands, in many cases in different languages depending upon the miners’ ethnicities.

The adaptation of electric power, coupled with the introduction of the diesel engine and storage battery for trolley locomotives, reduced the use of animals.

Rising costs also had a formidable impact, including those incurred by feeding (corn, oats wheat and barley) and general animal care. There was also the cost of building underground stables to house mules along with the need for veterinary attention and blacksmithing to shoe the animals.

Overall, the contribution of animals was significant.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Garnets have been a highly collectible gemstone since prehistoric times, and Arizona is renowned for hosting some of the best specimens.

These gemstones are formed as a result of a combination of high temperatures and pressures. They crystallize in the cubic system. Six main types of the garnet group include almandine, andradite, grossular, pyrope, spessartine and uvarovite. The English term garnet originates from the Old French term grenat, meaning “red.”

Garnets are classified as a group of silicates containing aluminum, calcium, chromium, ferrous iron, ferric iron, magnesium, manganese and titanium. Silicates are classified as the largest and most common class of minerals. They are found in igneous and metamorphic rock with attributes of hardness, transparent, opaque-to-translucent glassy luster and an average density.

Early industrial uses of garnet included its use as a coating for sandpaper first manufactured by Henry Hudson Barton of Barton Mines Corp. in 1878. Its abrasive qualities are ideal for grinding and sawing stones. Almandine has been used as color for stained glass windows. Almandine and pyrope appear red due to the presence of iron. Uvarovite is a chrome garnet known for its fine emerald green color. Many of the world’s best specimens are mined in the Ural Mountains of Russia.

In Arizona, several sites produce gem garnets including pyrope. These include the Four Corners area in northeastern Arizona located on the Navajo Indian Reservation, at Garnet Ridge, 5 miles northwest of the Mexican Water Trading Post, and in Buell Park, 16 miles north of the tribal headquarters at Window Rock on the Arizona border with New Mexico. Pyrope garnets are popular among collectors and are fashioned into faceted stones averaging one-half- to 1-and a-half carats in size, with some up to 5 carats. Their appearance ranges from orange-red to deep ruby-red pebbles.

Almandine-Spesartine garnets are found at Lion Spring on the southwestern flank of Elephant Mountain in the Aquarius Mountains in Mohave County. The site has produced a wide array of sharp garnet crystals embedded in a light-colored rhyolite matrix.

The Washington-Duquesne area in the Patagonia Mountains is a place where garnets are common and are found as gangue rock resulting from local mining operations. The Empire Mine, patented by a Captain O’Connor in 1874, was originally worked by chloriders for the next several decades. Production included high-grade lead silver ore. The Duquesne Mining and Reduction Co. acquired the property in 1905. George Westinghouse, inventor of the railroad air-brake, served as the president, consolidating 84 patented lode claims including the Bonanza and Empire Mines. An aerial tramway was built to service the Pride of the West Mine to the mill and smelter at Washington Camp.

Andradite is named after the Brazilian mineralogist Josè Bonifácio de’Andrada e Silva, who first described its properties. Andradite, a calcium iron silicate that commonly occurs in contact metamorphic rock and impure limestone, is scattered throughout the tailings of the Empire Mine. These garnets appear dark-brownish green with adamantine luster and are stained black by oxide of manganese and iron. The green coloration is derived from the presence of chromium impurities. Some andradite crystals from this locality have been found up to 3 inches in diameter.

Stanley Butte in the Stanley district in Graham County, 25 miles south-southeast of the town of San Carlos, is another location for andradite sometimes appearing with grossular. At this locality andradite is found as massive material with green-tinted brown crystals up to 2 inches.

While many of the above localities were open to collecting garnets and other minerals and gemstones years ago, the transfer of land rights and titles to property have now made many of them off limits to visitation. It is best to contact local authorities ahead of time to better ascertain whether or not collecting is permissible.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Ajo, in western Pima County 125 miles west of Tucson, has one of Arizona’s best-known porphyry copper deposits.

It enticed small mining operations by the San Francisco syndicate known as the American Mining and Trading Co. as early as the mid-19th century, though its silver chlorides on the surface were originally discovered by Spanish explorers seeking a more direct route to the Pacific.

The site’s remoteness and technological limitations made ore transport challenging. High-grade copper ore was transported by teams of oxcarts across several hundred miles of desert to San Diego, where it was loaded on ships destined to sail around Cape Horn to Wales for smelting.

Later ventures involving mining promoters A.J. Shotwell and John R. Boddie also failed to fully exploit the deposit. Both foolishly invested in a contraption known as the McGahan Vacuum Smelter, touted as having the ability to extract copper and valuable byproduct metals without water or fuel. The apparatus was marketed by a swindler, Fred L. McGahan, who absconded with the investors’ money.

In 1911, the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co., whose operation was principally out of Bisbee, took an option on 70 percent of the stock of the New Cornelia Copper Co. Geologist Ira Joralemon, mine manager John Campbell Greenway and metallurgist Louis D. Ricketts successfully built a leaching plant at Ajo with the capacity of processing 5,000 tons of ore a day. This advancement served as a prerequisite for the open-pit mining operations that would follow to fully exploit the New Cornelia ore body, composed of the disseminated copper sulfide minerals chalcopyrite and bornite.

Water to sustain the operations was found several miles north at Childs Siding. A rail line was extended from Ajo to connect with the Southern Pacific Railroad at Gila Bend, improving ore transport.

Ajo holds the distinction of being Arizona’s first open pit mining operation, having begun with the first removal of overburden in December 1916, followed by more aggressive earth movement the following year.

At the time, the ore averaged 3.66 percent with 86 cars of it having been shipped to the Douglas smelter. World War I increased the market price of copper to 25 cents a pound, covering the New Cornelia Copper Co.’s operating expenses while enabling it to pay its first dividends to its shareholders in November 1918.

Leaching of the carbonate ore also was initiated and was later processed by electrolysis for the production of pure copper cathodes, lasting until the ore was exhausted in 1930. A concentrator for treating the sulfide ore was completed in 1924, reaching a capacity of 16,000 tons of ore daily by 1936.

During the 1920s, a fleet of 18 steam locomotives served the pit. They operated on a 2 percent grade covering the 2¾-mile distance between the bottom of the pit and the primary gyratory crushers.

Phelps Dodge Co. acquired the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co. in 1931, later expanding the pit with the stripping of part of Arkansas Mountain, the site of the former Cardigan mining camp. Four 22.5-cubic-yard end-dump haul trucks performed this task, avoiding the high cost of track haulage. Electric shovels began to replace the old-time steam shovels with a total of nine in operation by 1939.

Diesel locomotives began operating at Ajo in 1945. The first ones included two units that arrived from Morenci. Steam locomotives reached their zenith in 1947 with 17 rod locomotives operating at the open pit. Soon thereafter they were replaced with a combination of trolley-electric and diesel-electric haulage transport, reducing costs that effectively reduced the cutoff point or minimum grade of the ore selected for processing from that of waste rock.

Prior to the erection of the $8 million Ajo smelter in 1950, concentrates from the open pit were transported to the Douglas smelter. Within three years, the mill was increased to a capacity of 30,000 tons.

Low copper prices and high operational costs in the mid-1980s indefinitely suspended mining activity at Ajo. It is estimated that 445.9 million tons of ore were mined since 1900 with production of over 3 million tons of copper, 463 tons of molybdenum, 1.56 million ounces of gold and 19.7 million ounces of silver.

There remains the opportunity for Ajo to yet again contribute to Arizona’s mining history . The economic potential appears favorable after Freeport-McMoRan’s recent assessment that Ajo contains sulfide ore reserves of 482 million short tons, averaging 0.40 percent copper and 0.010 percent molybdenum, 0.002 ounces of gold and 0.023 ounces of silver per ton.

With the right economic conditions, Ajo may once again become a thriving mining town.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

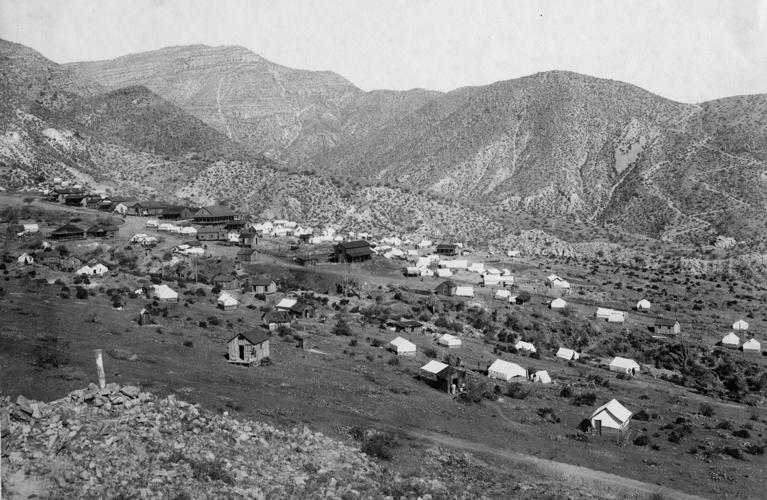

Like many copper mining towns in Arizona, Ray was booming in its heyday.

Ray — about 90 miles north of Tucson and 80 miles east of Phoenix — was the largest town in Pinal County in 1914, with a population of 5,000.

Located at the foothills of the Dripping Spring Mountains on Mineral Creek, it had a newspaper, the Copper Camp, and was the headquarters for the Valley Bank and Miners-Merchants Bank.

It also included many amenities such as the 12-room Ray Hotel, the Iris — a movie theater that subscribed to the movies of the day including those starring Tom Mix and Charlie Chaplin — and the Miller Bros. grocery and department stores.

Mining around Ray all began with a loose organization of silver prospectors in 1873.

But it soon developed into a more substantial mining operation with the erection of a five-stamp mill in 1880 by the Mineral Creek Mining Co. An English company, Ray Copper Mines Ltd., later failed in its attempt to exploit the ore at the site at the turn of the century because of inadequate sampling, leading to unrealistic expectations of higher-grade ore of 4 percent.

It was not until Daniel C. Jackling’s successful exploitation of the low-grade porphyry ore at Bingham, Utah, that similar potential was seen at the Ray Mine. With Jackling’s financial support, his associates Philip Wiseman and Seeley Mudd obtained options at Ray beginning in 1907.

Soon afterward, the merger of the Ray Copper Co. and the Gila Copper Co. formed the Ray Consolidated Copper Co. or Ray Con, which would later absorb the Arizona Hercules Copper Mining Co., Kelvin Calumet Mining Co. and Ray Central Mining Co.

In 1909, mining operations comprised 1,000 acres of lode claims around the town of Ray in the Mineral Creek Mining District. This prime land, part of a mineralized belt of highly altered and silicified schist running two miles east and west and one mile width north and south, enticed extensive development. More than 350 churn-drill holes were put down over 400 feet in depth. Of these, 277 holes indicated commercial ore averaging 2.17 percent copper below 250 feet of overburden, revealing an ore deposit consisting of disseminated chalcocite.

The churn-drilling program determined the potential of how much low grade ore could be mined in a large scale. The operation was overseen by Louis S. Cates, who initiated successful block caving methods that yielded over 8,000 tons of ore per day.

A mill was built at the juncture of the Gila and San Pedro rivers, producing copper beginning in 1911. Ore transport was by the standard gauge Ray and Gila Valley Railroad, a subsidiary of Ray Con. Built in 1909-’10, the railway from Ray connected eight miles to Ray Junction, the access point along the Arizona Eastern Railroad, which in turn transported it to the mill 18 miles away.

ASARCO built a smelter at Hayden in 1912 and contracted with Ray Con to smelt its concentrates, shipping the blister copper to its refinery at Perth Amboy, New Jersey.

With copper at 16 cents per pound in 1912, the company made a profit with dividends finally being made by June 1913. At the time, around 30 miles of underground exploratory work had been undertaken with 80 million tons of ore developed. More than $10 million had been invested in erection of the mill, railroad and equipment.

Advances in technology further made the deposit attractive despite lowering grade levels of ore. The use of a new flotation reagent made processing ore gravity concentration obsolete.

In 1917, Ray Con produced 44,500 tons of copper, ranking as Arizona’s second-largest copper producer. A 1918 panoramic image of Ray showed lines marked in the hillsides caused by caving ground resulting from the removal of underground ore. A distant building with four smokestacks contained an air compressor providing ventilation underground and compressed air for mining locomotives.

Ray Con was acquired by the Nevada Consolidated Copper Co. in 1926. Kennecott Corp. assumed control of its holdings by 1933 and direct control of the company within the next decade, forming the Ray Mines Division, Kennecott Copper Corp.

The block caving system developed by Cates saw drawbacks at Ray because of an area of tough rock that failed to fragment properly, along with mill extraction challenges based upon the mixture of sulphide and oxide ore.

By 1955, underground mining would be superseded by open-pit mining resulting from larger earthmoving equipment designed to transport greater amounts of ore, replacing railroad and hand laborers at the mine site while forever changing the surrounding landscape.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

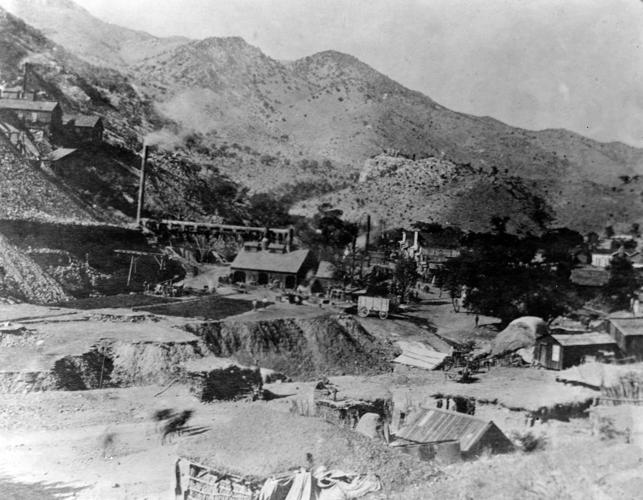

The Copper Queen deposit, dismissed by its discoverer as little more than “copper-stained rock,” turned out to be a massive body of copper-rich malachite that put Bisbee on the map.

Hugh Jones discovered the deposit in 1877, but — being not impressed — soon abandoned his claim to George Eddlemann and M.A. Herring. John Ballard and William H. Martin of San Francisco then acquired what became known as the Copper Queen prospect.

Both men, inexperienced in the mining profession, relied upon the advice of Ben and Lewis Williams, sons of prominent Welsh miner John Williams in Globe. John Williams was a partner with De Witt F. Bisbee in the brokerage firm Bisbee, Williams & Co. of San Francisco. The new town that sprung up near the copper prospect was christened Bisbee, after the man who provided much of the funding toward Ballard & Martin mining operations.

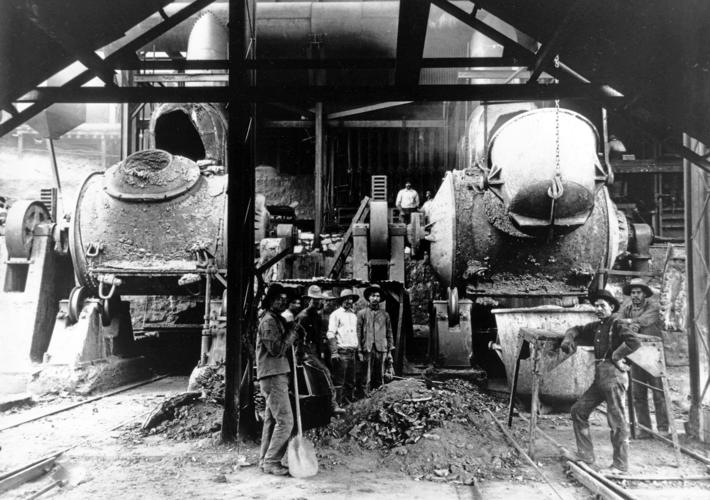

The town’s first smelter was built by George Center in 1880. It consisted of a 36-inch water-jacketed cupola. Fuel in the form of English coke was imported from San Francisco. The ore at the time was considerably high grade, averaging 23 percent copper. Development focused around a 50-foot open cut along with two parallel tunnels bored into a large body of limestone ore. The Copper Queen claim then comprised more than 640 feet of tunnels, cross-cuts and winzes penetrating the 160-foot-thick ore body.

Bisbee then had a population of 500 people.

Eastern metallurgist Dr. James Douglas was called to Arizona for the first time to evaluate the ore potential of the Copper Queen. Douglas gave high value to the mine, though it was already being negotiated for purchase by a Boston family.

Douglas also convinced the partners of Phelps Dodge to purchase the adjacent Atlanta claim, estimating a vast stockpile of minerals existed beneath the site. Phelps Dodge & Co. subsequently purchased the property from John B. Smitham, based upon Douglas’s recommendations in 1881, for $40,000. Douglas’s initial investment of $70,000 in exploratory work proved unproductive.

However, an additional $15,000 investment from investors enabled development that yielded the discovery of a great orebody by following a streak of ore, also called a “joker,” across the property line into the Copper Queen. The massive body of copper-rich malachite extended from the Atlanta property to the Copper Queen. Threats of litigation between the two mining operations necessitated the consolidation of both companies into the Copper Queen Consolidated Mining Co. in 1885.

Copper prices recovered in 1888, enabling the Copper Queen Consolidated Mining Co. to pay its first dividends in four years of $70,000. The rise in copper price from 11 cents per pound to 17 cents per pound was no doubt partly attributed to what became known as the Secrétan Syndicate, an attempt by France to corner the world’s supply of copper. This group of French metal speculators under the leadership of M. Secrétan secured control over the Anaconda Mine, the world’s largest producer of copper. Excess copper reserves would ultimately curb demand, causing the syndicate’s downfall a decade later.

On Feb. 1, 1889, the Arizona & Southeastern Railroad arrived in Bisbee from Fairbank, ensuring greater access to supplies used to erect the classic brick buildings still standing today in Brewery Gulch and Main Street. Coal and coke were imported for smelter operations while 6,000 tons of copper bullion, along with cattle from Mexico destined for Kansas City, was exported from the town. A ton of refined copper necessitated two tons of coke and two tons of bituminous coal.

By the turn of the century, Bisbee was an established mining community supported in a large part by the continued growth of the Copper Queen mining operation and increased ore shipments made possible by the Arizona & Southeastern Railroad.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

One of the prominent mines in the Harshaw district is the Trench Mine located 12 miles south of Patagonia in Santa Cruz County. It is credited with having produced high-grade lead-silver ore with its earliest workings dating back perhaps to Indian and Jesuit miners. The discovery of stone axes and hammers at the site in the 1870s attests to this possibility that they originally were used to mine clay and iron pigments.

Early descriptions of the mine discuss its iron-red outcroppings and profitable banded, porous and drusy ore fissure vein averaging 1 to 5 feet in width covering more than 20,000 feet on the surface. Its minerals include cerussite, pyromorphite and silver-bearing galena mixed with gangue rock including quartz, specular iridescent hematite, and rhodochrosite.

As early as 1858, the Trench vein in the Patagonia Mountains was worked using nearby smelters for ore reduction. The lead acquired was used in the manufacture of bullets. It was worked by Col. Harry Titus the following year and patented by James Ben Ali Haggin prior to 1872 and leased to a Mexican, Senõr Pádez (whose first name doesn’t appear in the records), later that decade. In 1875, the Trench Mine was credited with having produced 100 tons of argentiferous galena subsequently smelted at nearby adobe furnaces, providing a profit of $8,700 in silver.

Acquiring the mine in 1880, the George Hearst estate extensively developed the workings, sinking a 400-foot shaft and steam hoisting works enabling mine owners Haggin and Lloyd Tevis to mine rich ore. William Powers, another owner of the mine and a pioneer of the Patagonia Mining district, also worked the property, which consisted of two several-hundred-feet-long tunnels, at a profit of $4,400. A native of Ireland, Powers was known by citizens of Patagonia as “Mayor”. He was credited with having shipped several carloads of silver ore to the Crittenden smelter built by the Marder Luse & Co. near old Camp Crittenden. The ore was said to average 40 percent lead and 60 ounces to the ton in silver.

The mine was later optioned to Sen. W.A. Clark, owner of the United Verde Mine in Jerome. His operation included 20 miners in 1915. Between 1905 and 1920, the mine produced 1.5 million pounds of lead and $80,000 worth of silver.

Beginning in 1939, the Trench Mine and neighboring Flux Mine were operated by Asarco, producing 950,000 tons of sulfide ore treated at a 200-ton/per day flotation mill located at Trench Camp, one mile west of the town of Harshaw. The mines were described by miners as having poor ventilation causing sickness relating to the off gassing of rotten timbers found below.

Several onsite buildings at the property included a 35-by-50-foot boarding house, an assay office, a power house consisting of four big diesel engines, and a cantina. A tent city near the mine provided the miners with cheap housing.

Mining activity continued into the 1960s with both the mining and milling of lead-zinc ores onsite. Electric power for milling operations was supplied by the Citizens Utility Co. The crushing plant and floatation concentrator were operated by James P. Nash and E.W. McFarland. The operation consisted of 40 miners working six days per week with an average production of 1,000 tons of lead-zinc ore per month. The mill also handled custom ores including the lead zinc-copper ores from the nearby Flux Mine. Concentrates were shipped by rail to the Asarco El Paso smelter. Low-grade ore past the 670 foot level forced mining operations to cease by 1965. By 1968, the mill was removed from the property.

Asarco conducted an extensive drilling operation around the Trench Mine during the 1970s in search of porphyry copper. Since the 1980s, Asarco had been involved on and off in remediation of the land surrounding the mine site, some of which involved the use of artificial wetlands as a means to treat acidic mine drainage.

Today the 250-acre Trench Mine site owned by AZ Mining Inc. (formerly Wildcat Silver Corp.), a Canadian mineral exploration company, is conducting exploratory drills to determine the size and richness of the ore body. Current estimates include the potential of mining $13 billion worth of metals from its mining properties, including the Hermosa deposit in the Patagonia Mountains.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

One of Arizona’s renowned mining engineers was Louis Davidson Ricketts (1859-1940.) His contributions to mining operations in Arizona and Mexico in the late 19th and early 20th centuries enabled the greater development of second-grade ores on a massive scale for a profit.

Originally from Maryland, Ricketts was a graduate of Princeton University, where he received dual degrees of doctor of science in chemistry and economic geology. In his first assignment he was a Colorado mine surveyor.

Phelps, Dodge & Co. tapped the talented young metallurgist to conduct multiple surveys of the mineral resources of northern Mexico in 1895. Ricketts recommended several mining properties then owned by the Guggenheim family, who made their money as merchants and also held multiple investments in smelters in the United States (including ownership of the The American Smelting and Refining Co.) and Mexico.

Upon Ricketts’ recommendation that they would be a wise investment, the northern Mexico properties became part of Phelps Dodge’s Moctezuma mining operation in 1897. William E. Dodge, Jr. and James Douglas hired Ricketts as general manager of the Moctezuma Copper Co. to develop the newly acquired properties, which included building a five-mile-long narrow-gauge railroad line that connected the mine at Pilares to a large concentrator with a daily capacity of 500 tons and two 42-inch blast furnaces. A town was also built to service the mine at Nacozari.

The mine itself proved a profitable venture, yielding an average 3 percent copper in a copper market of 14 cents a pound with an average cost of 9 cents per pound to mine.

Ricketts also designed several large concentrators for the Detroit Copper Mining Co. One, known as the West Yankie concentrator, began operations at Morenci, Arizona in February 1900, following installation there of some of the earliest conveyor belts in the Southwest in the 1890s. Ricketts’ contributions were also invaluable in the reopening of mining operations at Globe, where he built a surface plant and reopened mines of the Old Dominion Copper Mining and Smelting Co., while serving as general manager for the Old Dominion Mine.

In 1905, he went on to construct a large washing plant at Dawson, New Mexico benefiting Phelps Dodge coal mines. Two years later he became president and general manager of the Cananea Consolidated Copper Co., designing and constructing a new concentrator in Cananea, Mexico.

The Calumet & Arizona Copper Co. enlisted Ricketts’ services in 1911 to design a smelter two miles below Clifton. The same year, Ricketts and John C. Greenway convinced the Calumet and Arizona to obtain an option on the available stock of the New Cornelia Copper Co. at Ajo. Their interest was in the massive sulfide ore deposit, which they believed contained 50 million tons of copper. But extraction would be costly, as the deposit lay over 120 million tons of low-grade copper ore overburden estimated to cost $6 million to remove.

However, Ricketts’ engineering acumen enabled him to discover a method for treating the oxidized overburden on a large scale. Using the Ajo leaching process, which he is credited with developing, Ricketts proved that the overburden could be processed with sulphuric acid, enabling its copper content to be recovered by electrolysis. This discovery, made at a small one-ton-per-day plant at Douglas, evolved into a 5,000-ton leaching plant which removed the overburden at a profit.

Ricketts also served as consulting engineer for Inspiration Consolidated at Miami, exploring ore bodies and developing the mine by sinking twin hoisting shafts, constructing a plant and railroad, and building Arizona’s first flotation mill to extract low-grade copper at 14,000 tons of copper per day in 1915.

He was held in high esteem by Arizona Gov. George W.P. Hunt, who christened him “First Citizen of Arizona” at the San Francisco Exposition of 1915.

In 1921, Ricketts again partnered with Greenway in building the 47-mile Chihuahua & Oriente Railroad to serve mining interests in Chihuahua, Mexico.

Ricketts continued to give Phelps Dodge sound advice, recommending that despite declining output of the mines in Ajo, Bisbee and Jerome during the Great Depression years, the priority remained in exploration and development of new ore deposits. He also supported the interchanging of scientific knowledge among competing companies to better exploit new ore discoveries.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

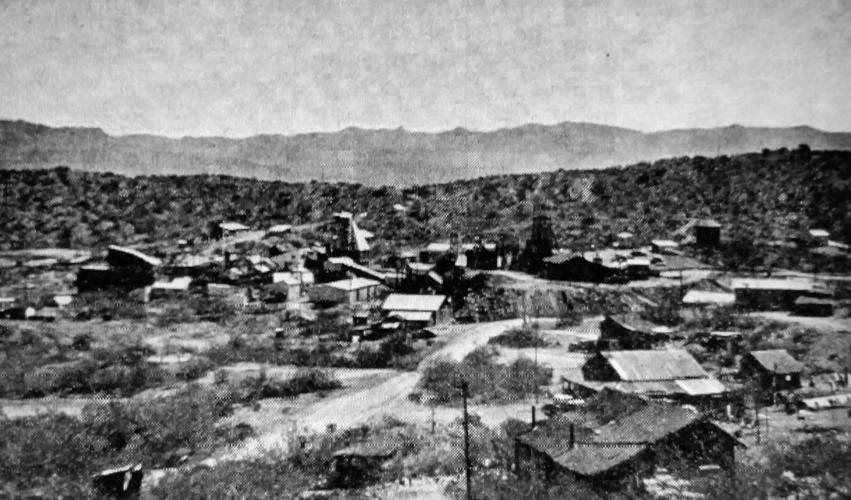

Beginning in 1881, the Old Dominion Copper Mining Co. played a dominant role in mining operations around Globe.

Having merged with the Old Globe Copper Co., it soon acquired the original Globe Ledge claims once owned by Ben Reagan, one of the mine’s original discovers, who also held interest in the nearby Silver King Mine. The Globe Ledge claims, including the Alice and Interloper at the southeastern base of Buffalo Hill, later became known as the Old Dominion Mine — named after Virginia, home state of the wife of one of the original prospectors.

The Old Dominion vein was estimated as running 3 miles, striking northeast, with rich copper ore — some parts averaging as high as 20 percent copper. The mine would soon become one of the greatest suppliers of copper ore in the Globe-Miami Mining district.

Operations around 1881 included a small furnace one mile west of the future town of Miami. Emphasis was placed on copper silicate ore from a small schist deposit. Proving unprofitable, the smelting operation was relocated to Globe, with upgrades including two operational 30-ton furnaces in 1884. Several decades elapsed, which included reorganization as the Old Dominion Copper Mining and Smelting Co. in 1895, the arrival of the railroad in 1898 and a smelter upgraded to a daily capacity of 2,400 tons.

In 1904 Phelps Dodge controlled the majority of company stock in the Old Dominion Co. with James Douglas as its president. Dr. Louis D. Ricketts became general manager at the mine site. Ricketts had a background in modernizing plant equipment; these improvements enabled less costly operations. The Old Dominion Mine paid its first dividends in 1907.

By 1908, $2.5 million had been invested in the modernization of the Old Dominion Co.’s refining works. This included building six new furnaces at the smelter, enabling a monthly capacity of processing 3 million pounds of copper.

The mine was serviced with pumps capable of pumping 10 million gallons of water daily for municipal use at Globe and Miami, along with 22 cubic foot capacity tramcars. The Old Dominion Railroad included a Porter locomotive and 50-ton ore cars connected the mine, mill and smelter.

The town of Globe saw its greatest growth during the first decade of the 20th century based upon the success of the Old Dominion Mine as smaller businesses in town thrived. However, the town faced challenges including a flood during the summer of 1904 when Pinal Creek overflowed its banks.

The Old Dominion Mine also faced a series of setbacks, including a fire that occurred in the Interloper Shaft, claiming the life of three miners from asphyxiation, along with cave-ins. A mine strike in 1917 initiated by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) also took its toll on production, and four units of the Seventeenth United States Cavalry from Douglas were sent in to defuse the situation.

Postwar challenges including decreasing ore grades, from 5 percent copper to less than 2.5 percent; aging equipment; and flooding. The smelter closed in 1924 when the International Smelter at Miami assumed processing the mine’s concentrates.

It is estimated that the mine produced 800 million pounds of copper, bringing returns valued at $134 million, prior to its closure in 1931 when the Old Dominion Copper Mining and Smelting Co. succumbed to the challenges wrought by the Great Depression.

In 1940, the mine was acquired by Miami Copper Co. for $100,000. Water was pumped out of the mine to supply the company’s mining operations at Castle Dome, Copper Cities and Miami. Mining operations have occurred at the Old Dominion Mine since, including the open pit mining of hematite by lessee B.J. Cecil Trucking Inc. for the Portland Cement Co. at Rillito in the 1970s and ’80s.

The Old Dominion mine site today functions as a historic mine park and the only self-guided mine tour in Arizona where visitors can view old mining equipment, concrete foundations, excavations and interpretive plaques. It also provides a source of water to the Pinto Valley open pit copper mine operated by Capstone Mining Corp. five miles west of Globe. The foundation of the smelter built in 1906 can still be seen from the Globe-Miami highway.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

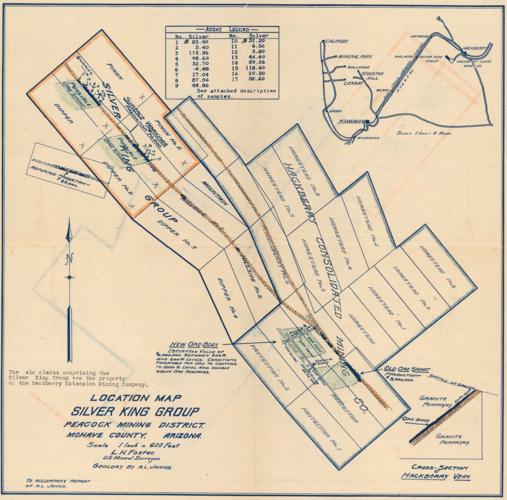

Four men were wandering the northeast slope of the Peacock Mountains in search of water on Oct. 12, 1874, after their horses were taken by Indians when they discovered a silver ledge that became the Hackberry Mine.

Samuel Crozier, William Ridenour, J.D. Putman and J.A. Kile filed the first mining claims at Hackberry, which they named after a tree they saw by a nearby water source. The Peacock Mountains are in Mohave County in northwestern Arizona.

Early operations, as part of the Silver King group of mines, involved chloriders using windlasses to excavate high-grade silver ore at 50 feet or less in depth. They packed their ore on burros to be transported for processing at a nearby amalgamation mill.

In 1876, a San Francisco group of investors purchased the mine, located 27 miles northeast of Kingman in the Peacock Mining district. Soon after, the mine yielded 222 bars of silver valued at $222,705.

After being shut down over mismanagement, it was taken over by the Hackberry Mining and Milling Co. in 1881. It operated until 1884.

Around this time, the town of Hackberry, a mile and a half east of the mine, gained prominence with the opening of a general store by James Dundan. Also, Dr. Warren E. Day opened up medical offices to care for men who worked for the Arizona Pacific Railroad. The killing of a town local by an outlaw prompted the town’s first hanging.

The population reached 400 and the town was soon relocated several miles closer to the railroad. It served as a major shipping point for cattle in the late 1890s and as a stop for the railroad, serving as the only source for fuel oil between Seligman and Needles.

Exploration and development prompted the Hackberry Mine to reopen in 1914 due to discovery of a large tonnage of low grade or milling ore left behind at the site. Technological advances in oil flotation enabled miners to extract these remaining ores at a profit. The mine was credited with $750,000 to $3 million in silver and gold production from 1875 to 1917. However, litigation matters hindered full development of the mine’s reserves.

A report provided by mining engineer A.L. Johns in 1918 described a 22-foot wide and 19-foot high vein at the 600- and 700-foot levels of the mine, averaging 32 ounces of silver per ton. Johns reasoned the mine had the potential to produce 450,000 mineable tons, along with secondary deposits of gold, copper, lead, zinc and cadmium.

The mine was then operated by James Murray, a renowned mine owner in Butte, Montana, along with William Neagle and Gus S. Holmes. A 200-ton flotation mill was built near the collar of the shaft.

Flooding in 1921 caused the mine to be shut down again. Intermittent lessee operations at the mine site continued over the ensuing decades. A small shipment of 1,117 tons of copper by mine lessee Henry Galbraith was shipped to a local smelter in 1943.

Work commenced in 1980 with three 4,000-ton capacity leach pads constructed to cyanide leach the Hackberry Mine dump. Water was acquired from a nearby old mine shaft. An onsite bullion furnace was built to smelt and refine the silver. Thomas A. Roberts operated the mine, incorporated as Northern Arizona Minerals and owned by Nicholas Hughes of Las Vegas. His operation involved dewatering and underground ore sampling. The mine was described as including 12 patented and 10 unpatented lode mining claims replete with five shafts. The main shaft is 950 feet deep.

The property is currently owned by the Hughes Family Trust.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

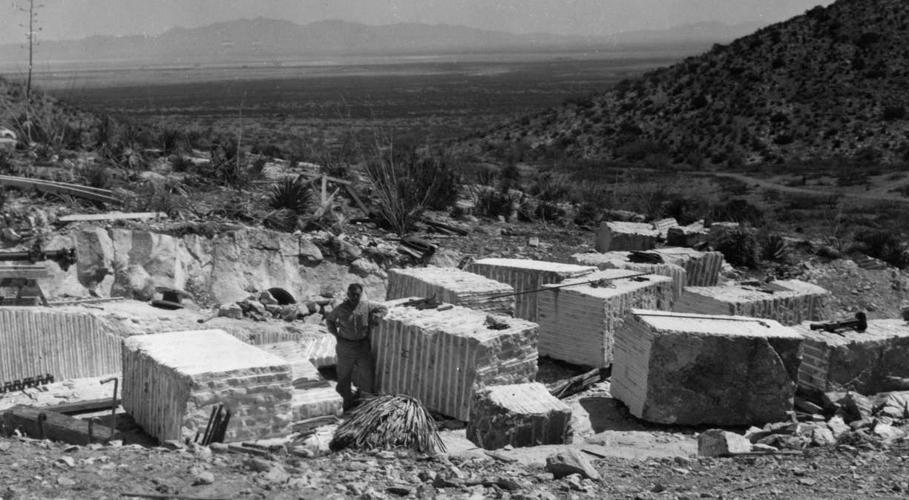

The Ligier black marble quarries, discovered in 1909 three miles south of the town of Dragoon, were considered comparable in quality to the famous Carrara marble quarries of Italy.

Discoverer and namesake L.R. Ligier noted the black, weakly marbleized limestone with white calcite stringers in the Golden Rule metallic mineral district in the Gunnison Hills of the Dragoon Mountains.

He wanted to immediately exploit the site, as the high-grade marble would polish well and be resistant to weathering. However, litigation, world wars and protracted economic crises prevented production until the late 1940s.

The quarries became a family affair operated by the Ligier brothers, who shipped marble to Los Angeles, St. Louis, Kansas City, New York and Carthage, Missouri. The Ligier quarry shipping operation benefited from being only several miles from the main line of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

D.G. Ligier corresponded regularly with potential investors to finance the operations, even soliciting Charles H. Dunning of the Department of Mineral Resources for the state of Arizona for a contribution of more than $200,000. Ligier claimed the Dragoon Mountains quarry would become the future marble capital of the world. He emphasized the paucity of decorative marble quarries existing at that time in the United States and the need for decorative marble in the manufacture of tabletops, ashtrays, lamp stands and inkwell sets.

The Ligier operation produced terrazzo chips, a highly sought-after, colorful, crushed marble aggregate product. In 1949, the terrazzo was reported as selling for up to $35 per ton. D.G. Ligier believed the property could produce 40 tons per day.

The property developed into seven quarries by 1953, providing 20 varieties of marble. Commodities included surface marble and crushed stone. Mineral specimens included hubnerite, wollastonite and massive scheelite.

Production during the mid-1960s averaged 75 tons per week. The mine served the growing West Coast market for terrazzo chips and for materials used in prefabricated concrete slabs. A large shipment of blue terrazzo chips packaged in burlap sacks and transported by 22-ton truck loads from the mine reportedly was used in the erection of the Sears Roebuck & Co. building in Phoenix. The product was also used in roofing chips, chicken grits, stock feed, wainscoting and for flux in the mining industry.

Ligier-Arizona Marble Quarries Inc. reorganized in 1962 as Dragoon Marble Quarries Inc. At the time the site was producing 11 colors of marble and eight sizes of the stone. Popular colors included green, red Verona, cream, white, pink, gray, purple and black opal.

A crushing and screening plant was in operation several miles from the quarries by 1963. Eight men worked the plant, quarries and general maintenance duties. Equipment included a cyclone dust collector, 30-ton crude ore bin, jaw crusher, hammer mill and three storage bins for marble. The operation was not without risk, as one man was killed on a loader. The Marble Quarries Machinery Co. was asked to provide greater-capacity processing equipment, thus enhancing the production and profit figures.

Intermittent production continued when the Marbella Co. leased the property in 1976, producing rose-colored marble. Jim Chapman served as the mine’s superintendent after the Lieger marble quarries were reopened in 1985, owned by the Ligier estate. Several of the claims, including those known as the Godfather, produced dimension marble for fireplaces.

The mine is now within the boundaries of Coronado National Forest. Its surface area is comprised of fractured rock and devoid of soil and vegetation. Several attempts recently were made to reopen the quarries accessible on Lizard Lane or Forest Service road 689, formerly known as Dragoon Marble Quarry Road. One involved Alpha Calcit Fullstoff, an international producer of ground calcium carbonate, and its subsidiary company Alpha Calcit Arizona, beginning in the late 1990s. The company acquired the unpatented mining claims to the property and intended to mine the marble for use in high-quality paper production.

Further development at the quarries has been hindered, however, due to its classification by the Forest Service as being part of the Upper Dragoon Roadless Area. This classification remains controversial based upon the quarries’ altered landscape, small acreage and ease of accessibility by road.

SOURCES:

Bain, G.W. 1963. Marble Occurrences in the Dragoon Pass Area, unpublished geological assessment, 33p.

Duhamel, Jonathan. How bureaucratic errors are blocking a Marble Mine in Southern Arizona. Arizona Daily Independent. April 24, 2016. Accessible online at https://arizonadailyindependent.com/2016/04/24/how-bureaucratic-errors-are-blocking-a-marble-mine-in-southern-arizona/

Ligier Black Marble Quarries. 2011-01-2198, ADMMR mining collection, Arizona Geological Survey.

Ligier Black Marble Quarries. 2011-01-2199, ADMMR mining collection, Arizona Geological Survey.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

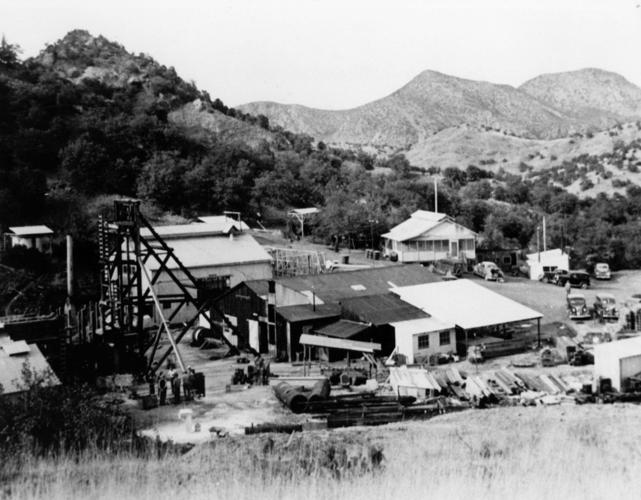

Although prospecting was undertaken as early as the 1850s in what became known as the Mammoth Mining District or the Old Hat Mining District, it was not until 1881 that mining intensified.

Located 3 miles southwest of the town of Mammoth on the San Pedro River, the area on the east flank of the Black Hills, a low range north of the Santa Catalina Mountains, saw the development of the Mammoth, Mohawk and New Year properties occurring on what came to be known as the Mammoth vein after its discovery by Frank Schultz.

A 30-stamp amalgamation mill financed by profits made from the discovery of gold ore at the Mammoth Mine by C.R. Fletcher and associates was conveniently built at Mammoth to process the ore from surrounding mines. The mill was heightened to 50 stamps after Mammoth Gold Mines Ltd. acquired the property in 1889.

The Mammoth Tiger Extension Mine, also known as the Ford Mine, was discovered in 1879, reportedly shipping a small quantity of high-grade lead/silver ore shortly thereafter. By 1920 it was shut down due to the expense associated with water removal.

A 900-foot shaft sunk from the neighboring Collins, Mammoth, Mohawk and New Year mines to the east successfully drained the water from the Ford Mine.

By the time it was acquired by the Mammoth-Tiger Extension Mining Corp. in 1942, it consisted of 1,400 feet of underground workings along with a retimbered shaft, a new gallows headframe and the mucking out of all the winzes, stopes and tunnels.

Mining engineer Sam Houghton optioned the New Year Group of mines in 1926.

The development of a 140-foot-deep shaft followed with the discovery of profitable quantities of gold, vanadium and lead.

Despite the Great Depression, rising gold prices in 1933 enabled Houghton to promote his mines. That year, the New Year mines and the Mohawk Mine were acquired by the Molybdenum Gold Mining Co., a subsidiary of the Molybdenum Corp. of America. The company, employing 32 men, continued to develop the underground mines while erecting a cyanide plant.

In 1934, the company was shipping several carloads of ore to the Molybdenum Corp. refinery in Washington, Pennsylvania. An onsite 200-tons-per-day gravity concentration and cyandidation mill was built in 1935.

As business increased, the mill was modified to handle 300 tons of ore per day, replete with a gravity concentrating plant consisting of six concentrating tables. The tailings were then sent to a cyanide leaching plant for recovery.

In 1939, the Mammoth-St. Anthony Mining Co. Ltd. acquired the Mohawk and New Year mines from the Molybdenum Gold Mining Co. The consolidation of mines, including that of the Mammoth Mine, under the control of a single company resulted in the formation of the town of Tiger, which reached a peak population of 1,800 people.

Mining operations at Tiger were focused on producing strategic metals during World War II.

The U.S. military sent several dozen men to aid in mining operations at Tiger because of a lack of manpower due to wartime conscription. Tiger was also the site of only one of two plants that could successfully process molybdenum and vanadium from other metals.

The mining property was purchased by the Magma Copper Co. in 1953, and operations were suspended due to the declining market prices for lead and zinc.

Credited with having produced 400,000 ounces of gold, 1 million ounces of silver, 3.5 million pounds of copper, 75 million pounds of lead, 50 million pounds of zinc, 6 million pounds of molybdenum oxide and 2.5 million pounds of vanadium oxide, the Tiger property was later worked by lessees for gold-bearing tailings and later subject to reclamation under BHP Billiton Ltd.

Tucson Wash just west of the Tiger property connected the towns of Mammoth and Oracle in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

It is now a popular adventure excursion for off-road vehicles and mineral collectors seeking wulfenite crystals at the Ford Mine accessible from the wash.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Dennis O’Brien and William Tweed located the Christmas Mine about 1880 and sold their claims to Phelps Dodge shortly thereafter. Yet the mine could not be exploited until the land was removed from the San Carlos Indian Reservation boundaries in 1902.

Claims staked Christmas Day that year by G.B. Chittenden and N.H. Mellor gave the mine and subsequent town its name. The town’s population reached 1,000 by 1932 and its post office (1905-1935) was highly sought after for its “Christmas” postmark by people sending letters or postcards over the holiday season.

The mine, located on the eastern slope of the Dripping Springs Mountain Range, about eight miles north of Winkelman in the southwestern corner of Gila County along Arizona 77.

Mineral deposits were found in Naco limestone with a capping of andesite on the surface. The Christmas ore body in the Banner Mining District proved challenging to mine because of its irregular and faulting contours. Ground support also proved challenging necessitating the prompt filling of mined areas.

Abundant ore minerals include chalcopyrite, bornite, chalcocite, covellite and cuprite mixed with gangue rocks garnet, magnetite and quartz.

A dispute between Phelps Dodge and the Saddle Mountain Mining Co. in the early 1900s was settled in court with the latter retaining the property and erecting a small smelter.

Production began in 1905 with a succession of mining companies intermittently operating the property throughout most of the 20th century.

A 7,300-foot-long wire rope Bleichart aerial tramway was built on the property in 1916, with a carrying capacity of fifty tons per hour. It ran from a 250 ton ore bin at the No.3 shaft to a 1,000 ton ore bin nearby the Arizona Eastern Railroad connection, an elevation gradient of 950 feet.

The rail transported the ore for processing at the Hayden smelter near Winkelman.

Surface hauling involved the use of a one-ton Ford truck and a two-ton Nash Quad truck.

The mine received electricity from the San Carlos Irrigation Project via a 66,000-volt transmission line nearby the main shaft.

The mine was known for the production of high lime fluxing ore sold by the Sam Knight Mining Lease Inc., which leased the property in 1939. Its primary customer was the Hayden smelter that used the product to treat the copper concentrate received from the nearby Ray Mine.

By 1942, ore from the Christmas Mine averaged a percentage slightly above 2 percent copper and around 30 percent lime. Gold and silver averaged 0.005 ounces per ton and 0.23 ounces per ton, respectively.

The McDonald shaft reached a depth of 1,780 feet, with several drifts running in excess of 1,200 to 2,400 feet. The surface structures included a compressor building, hoist, change house, office and warehouse. Ore was hauled by electric locomotive from the haulage tunnel 400 level 2000 feet to the flotation mill built by the Southwestern Engineering Co. in 1929 on the surface near the (main) No.3 shaft.

In 1962, the mine employed 142 men, working three shifts and producing 600 to 800 tons of ore per day. The stopes were 18 feet high by 18 feet wide on the 1,400-foot level worked by miners using Ingersol-Rand drills.

Underground water continued to be a problem necessitating the use of three Hazleton pumps to pump 2,500 gallons per minute.

Open-pit mining operations were carried out by front-end loaders beginning in 1966. Floatation was applied to both sulfide and oxides ores with 90 percent recovery on sulfides and 50 percent recovery on oxidized material.

The John Mediz rock shop in Globe secured a contract with the Inspiration Consolidated Copper Co. (then the property owner) enabling it to collect mineral specimens including apophyllite, dioptase, kinoite and silver from the property in 1980. Declining copper prices forced the mine to close in the early 1980s. It is estimated that 480 million pounds of copper ore were mined on the property, most notably during open-pit mining operations.

Analysis undertaken of the property in 1987 by John Kuhn, a consulting geologist, revealed a good stockpile of oxide copper ore around 100 million tons averaging 0.47 copper per ton. Kuhn also reported on the potential of processing the surrounding pyrite for the purpose of manufacturing sulfuric acid.

The property is currently owned by Freeport-McMoRan, which is researching the size and scope of the Christmas copper ore body.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Canyon Diablo, an anglicized version of the Spanish word for “Devil’s Canyon,” is a well-known and formidable deep gorge surrounded by flat land in Kaibab limestone that halted the construction of the Atlantic Pacific Railroad for six months in 1881.

Located 35 miles east of the San Francisco Peaks just north of Flagstaff, the canyon was surveyed and named in 1853 by Army Lt. Amiel W. Whipple, who was exploring the topography of the 35th parallel for the feasibility of building a railroad across northern Arizona.

The need for rail transport became apparent with the opening of mining camps in Mojave County in the late 1870s. Those included Cerbat, Hackberry, Mineral Park, Signal and White Hills mining operations.

The A&P’s route connected Springfield, Missouri to California through Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Kingman served as the railhead along the A&P for many of these nearby mines.

The A&P was the closest major railway for mining operations around Prescott, notably in the Bradshaw Mountains. The railroad served as the primary method of ore transport especially for mines with contracts at smelters operated by the Pueblo Smelting and Refining Co. of Colorado or the Rio Grande Smelting Co. of Socorro, New Mexico.

Three notable bridges were built for the railroad at Canyon Diablo. The first in 1881 consisted of a one track width(iron). Provisions, including water, were hauled by wagon from Navajo Springs 100 miles to the east.

During the summer of 1881, stone cutters were requisitioned from as far as Chicago and St. Louis, crafting local rock into the bridge-tower footing or pylons still evident today.

The small ephemeral settlement of Canyon Diablo was built to serve the railroad.

Consisting of a nearby telegraph office it was notorious for a number of gun fights and robberies. It also served as a shipping point for wool from local sheep herders.

Iron used in the construction of this edifice was manufactured by the Central Bridge Works in Buffalo, New York. It required 20 railcars to transport the structure in October 1881. The bridge came up several feet short causing the need to import more material necessary for completion.

The first trains to pass over the canyon occurred on July 1, 1882. The bridge measured 550 feet, crossing over a 225-foot-deep basin.

Finishing touches in the weeks that followed included the addition of a wood floor laid across the bridge, the installation of substantial iron railing and the removal of the scaffolding.

The overall product consisted of 11 spans, with 2 measuring 100 feet in length. Two more measured 30 feet in length while the other seven spans measured 40 feet in length. The total cost was $250,000.

No doubt intimidating was the first bridge’s light timbered appearance. The maximum speed of the passenger cars across its rails was four miles per hour, 20 mph less than the standard maximum.

The site was also the scene of the infamous train robbery that occurred at Canyon Diablo station in 1889. An eastbound passenger train had stopped to lubricate the driving mechanism of the locomotive when a group of four men with six-shooters held up their travels. The bandits made off with $800, leaving a safe containing $125,000 behind.

The bandits were eventually captured southeast of Beaver, Utah by a small posse led by the sheriff of Yavapai County.

The A&P was acquired by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Co. in 1897.

By 1900, the bridge was replaced with a structure of more sturdy manufacture to handle the greater weight of locomotives and rail cars.

Herman Wolf was a proprietor of one of the trading posts at Canyon Diablo. The spelling was changed from Cañon Diablo to Canyon Diablo by the Santa Fe Railway in 1902.

Constructed under the oversight of System Bridge Engineer Clifford Sandberg, the double-track, steel-arch bridge seen today was completed in 1947. Its length is 544 feet while its arch measures 300 feet.

The bridge is heavily used today by trains averaging 50 mph.

Both the bridge and nearby Canyon Diablo settlement remnants are accessible by a three mile rough dirt road north of Two Guns, off Interstate 40.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

From 1908 through World War I the Vekol Mine was heavily prospected with a 400 foot shaft dug yielding little production.

Some ore shipments were made after a group of Phoenix investors took over the mine in 1918 installing concentrating tables and reconditioning the mill to work the mine dumps.

Paul A. Daggs acquired the mine, then composed of six patented claims of which the Vekol being the greatest producer along with the Argosy, Lookout, Flat Iron, Mount Vernon and Grandfather. It included a 40-ton mill, three steam power hoists, air compressor and assorted buildings including a machine shop, carpenter shop, office and laboratory.

The Reward Mine five miles east of the Vekol Mine was discovered and developed during the early 1880s and worked with success by the Reward Mining Co. It included a 110-foot incline and 800-foot well to sustain a small water-jacket blast furnace.

Production involved 37,660 pounds of black copper comprising 26 percent grade in 1884 valued at 13 cents per pound. Worked again in the early 1900s through World War I, it shipped high-grade ore to the El Paso smelter in 1907-08, producing 450,000 pounds of copper valued at $75,000.

E.J. Bonsall developed the nearby Copperosity Mine in 1890 and some ore was shipped from incline shafts. In 1907 the Copperosity Mining Co. briefly operated the mine.

World War I saw the development of a two compartment vertical shaft developed the ore body at several hundred feet. High grade ore was stoped and transported to Casa Grande for shipping to the refiner. Total production was 360,000 pounds of copper valued at $80,000. Credited with $45,000 in gold production; the nearby Christmas Gift Mine included a thick pocket of high-grade gold ore associated with galena along with cerussite outcrops that appear on the surface.

During the 1950s, the bank and assay office building still stood at Vekol. Two brothers by the name of Elliot operated the mine using the old safe in the assay office as a cupboard.

The Vekol Mine was leased and optioned from Federal Mines to Mineral Harvesters Inc. during the mid-1960s. Emphasis was on working the tailings and mine dumps. The operation included a straight line motion jig that successfully ran dry providing an 8:1 concentration ratio of dump material averaging $8 in lead and $4 to $5 in gold and silver per ton.

Between 1882 and 1965 the mine was credited with having produced 100,000 tons including 753,000 pounds of copper and 95,000 pounds of lead, along with 500 ounces of gold and 1 million troy ounces of silver from pods and lenses of oxide ore.

Newmont Mining Co. became interested in the Vekol property negotiating with the Papago Tribe involving a $1 million deal to build a custom copper smelter. However, it failed to meet the necessary $45 million investment to put the mine back into production.

The Argosy Mining Co. acquired six patented claims comprising the Vekol Mine in January 1983 investigating the economic potential for processing dump material while initiating a leaching operation, and a geological mapping program to seek out additional ore reserves.

It was determined that in order to mine by open pit operation it would require the removal of 62 million tons of overburden before the sulfide ore zone could be effectively mined.

A sulfide flotation plant using water from local wells would need to be established along with a pit reaching a depth of 1,200 feet. Projected annual production of copper was 66.5 million pounds along with 1.2 million pounds of molybdenum. Secondary mineral production also included gold and silver treated off site.

After leaching operations were suspended in 1984, Bill Ewing leased the mine from Wilson, Clemons and Westling. He undertook some air-track drilling for silver and lead bearing faults however; assays of the fault material proved low metal values.

Today the Vekol Mining district holds interest among treasure hunters who actively seek out a cache of 300 silver ingots weighing 25 pounds a piece rumored to have been buried several miles north of the mine site in 1891. It also holds an interest among mineral collectors seeking out chlorargyrite (a silver ore mineral) and ferroan dolomite crystals in the mine dumps. The area is also a corridor for illegal immigration and drug smuggling.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

- Updated

Vekol was a premier silver mine in the southwestern corner of Pinal County on the western side of the Vekol Mountains.

Surrounded by the Papago Indian Reservation, it is located 30 miles southwest of Casa Grande in the Casa Grande Mining District. The ore was concentrated along a north-south trending fault in shaly limestone dipping 10 to 30 degrees to the southwest.

The mine itself was discovered by the Papago Indians and christened Vekol after the tribe’s term for “grandmother”.

Judge John D. Walker was the original mine owner having been informed about the mine’s whereabouts by Juan José Gradello, a Papago Indian in 1879.

Originally from Illinois, Walker settled in Arizona Territory in the 1860s becoming both a rancher and a miner. He fought against the Apache Indians in 1864, having led several contingents of Papago Indians.

Among the Papago he was respected.

Walker in turn learned the Papago language and took concern for their well being.

Ore samples from the mine were sent to John Walker’s ranch on the Gila River. The samples were assayed showing a high value of silver.

Walker formed a partnership with his brother Lucien and P.R. Brady in 1880. In 1884, Brady would relinquish his one-third interest of the mine to the Walker Brothers for $65,000 over a disagreement of the mine’s operation.

By 1881, development of the mine hastened with the main shaft sunk to a depth of 118 feet. It was a profitable venture with 10 tons of ore shipped monthly to the Selby smelter in San Francisco, and smelters in El Paso and Denver averaging a value of $300 per ton.

Enterprising individuals, the brothers stockpiled 150 tons of second grade ore valued up to $90 per ton.

The mining camp of Vekol, at an elevation of around 1700 feet, lasted 12 years. It consisted of over 200 inhabitants, including 100 miners.

The camp was unique in that it lacked both churches and saloons. It did have a boardinghouse, post office active from 1888 to 1909, school, and public library.

The camp was also a destination along the Casa Grande & Quijotoa Stage Line, which left Casa Grande daily to the Quijotoa mining camp. It stopped along the way at the mining operations at Copperosity, Christmas Gift, Reward and Vekol.

Walker openly refused to allow alcohol into the camp. He also refused multiple offers for his mine from interested parties totaling $100,000.

Walker was revered among the town for his leadership, justice and sobriety.

A 10-stamp mill was built at the camp to process the mine’s low grade ores. It turned out a bar of silver bullion a day averaging 100 pounds in weight, according to press reports.

Water for the mill and for the 400 local Indians and cattle came from a drilled well at the mine 350 feet deep.

The mill ran between 1885 through 1889 averaging a rate of 470 tons of ore (valued at $16,000) per month, closing due to a decline profits in low grade ore.

Pan amalgamation was also used to acquire silver from crushed ore using a mixture of mercury, sodium chloride and copper sulfate in large vats.

The brothers followed a strike covering a distance of 1400 feet from the discovery point. Challenges occurred as they uncovered ore-bodies containing lead and zinc as they had an inadequate milling operation to treat the sulfide ores.

A dispute among the Walker brothers led to Lucien’s multiple attempts to have his brother John committed to an insane asylum. Fierce litigation between the brothers eventually led to the death of John Walker in 1891.

The litigation would continue between John Walker’s widow and brothers as to who would own the mine. They were finally resolved when the mine was bonded to a New Orleans and Texas Company who operated it in 1908.

During the Walker brother’s operation it is reported that between $1 million and $3 million dollars worth of silver ore was mined.

The Vekol Mine would continue to hold an interest to mining companies through much of the twentieth century.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Ore-hauling animals contributed economic savings and production to many of Arizona’s mining towns and camps of the past.

The expense of underground transportation constitutes a considerable percentage of the total mining cost in most mines, exceeding at times the expenditure of stoping (opening large underground rooms by removing ore), the Bureau of Mines has observed.

In the early years of underground mining in Arizona, miners known as trammers were responsible for pushing ore-laden carts. As mines became more developed, in excess of 500 feet, this operation became less efficient.

Mining companies found a solution, using animals to improve efficiency and economy for long-distance hauling.

Mules, draft horses, burros and oxen were traditionally credited with having participated in overland ore transport. Also supplying the power for hoisting material to the surface, they were later replaced by steam engines using steam from a boiler assembly.

Mule teams transported copper bars from the mines at Clifton-Morenci 1,200 miles to Kansas City, the closest railhead and access to markets.

Local transportation in mining towns also relied upon animal s. The Detroit Copper company store at Morenci offered the option to residents of home delivery for grocery supplies by burro or mule. Burros could also be seen transporting water in two canvas bags holding 40 gallons. The average cost was 50 cents a load.

Oxen were the beasts of choice for freighting ore from the mines in Bisbee and Morenci.

Mules have historically been the preferred animal for transport, weighing between 800 to 1,200 pounds. Mules are smaller than draft horses, require less headroom, have the ability to endure heat and are more robust when compared to the horses. They are less likely to become lame.

Unlike horses, which are prone to smash their heads against a low-lying underground drift, a mule would duck its head to avoid such a collision.

The cost of procuring good mules for mining operations ranged between $150 to $300, taking into account their condition, age and weight. Mules were expected to work underground between three to seven years. Afterward, they were retired, being brought to the surface at night and slowly re-exposed to daylight by being kept in a dark room lit by candlelight with increments of exposed daylight over the course of several weeks. Then, they were set free to run wild.

Mining operations at Bisbee relied upon mule haulage or tramming beginning in 1907, continuing through 1931. Earlier operations relied upon the miners themselves to move the ore cars by hand.

Obvious limitations arose, since miners could only tram a single loaded car in contrast to mules, which could move five or more cars. The cars weighed 800 pounds empty and around 2,800 pounds full. Mules possessed enough acumen to realize their limitations. When miners attempted to add extra cars , the mules chose not to move until the additional weight was removed.

Mules and horses working underground on average traveled 3 to 15 miles per shift.

A mule school existed at Bisbee on a hillside above Brewery Gulch to train young mules for underground mining. The school was composed of a circular track, one switch and 30 feet of straight track on a flat surface of the hill. Working without bridles or reins, mules were given their daily lessons of waiting at ore chutes until cars were loaded and directing cars by kicking switch points along the track with their hooves. They became proficient at gathering ore-laden cars from the loading faces to a siding on the main haulage way, afterward returning the empty carts.

They also quickly learned to follow voice commands, in many cases in different languages depending upon the miners’ ethnicities.

The adaptation of electric power, coupled with the introduction of the diesel engine and storage battery for trolley locomotives, reduced the use of animals.

Rising costs also had a formidable impact, including those incurred by feeding (corn, oats wheat and barley) and general animal care. There was also the cost of building underground stables to house mules along with the need for veterinary attention and blacksmithing to shoe the animals.

Overall, the contribution of animals was significant.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

Garnets have been a highly collectible gemstone since prehistoric times, and Arizona is renowned for hosting some of the best specimens.

These gemstones are formed as a result of a combination of high temperatures and pressures. They crystallize in the cubic system. Six main types of the garnet group include almandine, andradite, grossular, pyrope, spessartine and uvarovite. The English term garnet originates from the Old French term grenat, meaning “red.”

Garnets are classified as a group of silicates containing aluminum, calcium, chromium, ferrous iron, ferric iron, magnesium, manganese and titanium. Silicates are classified as the largest and most common class of minerals. They are found in igneous and metamorphic rock with attributes of hardness, transparent, opaque-to-translucent glassy luster and an average density.

Early industrial uses of garnet included its use as a coating for sandpaper first manufactured by Henry Hudson Barton of Barton Mines Corp. in 1878. Its abrasive qualities are ideal for grinding and sawing stones. Almandine has been used as color for stained glass windows. Almandine and pyrope appear red due to the presence of iron. Uvarovite is a chrome garnet known for its fine emerald green color. Many of the world’s best specimens are mined in the Ural Mountains of Russia.

In Arizona, several sites produce gem garnets including pyrope. These include the Four Corners area in northeastern Arizona located on the Navajo Indian Reservation, at Garnet Ridge, 5 miles northwest of the Mexican Water Trading Post, and in Buell Park, 16 miles north of the tribal headquarters at Window Rock on the Arizona border with New Mexico. Pyrope garnets are popular among collectors and are fashioned into faceted stones averaging one-half- to 1-and a-half carats in size, with some up to 5 carats. Their appearance ranges from orange-red to deep ruby-red pebbles.

Almandine-Spesartine garnets are found at Lion Spring on the southwestern flank of Elephant Mountain in the Aquarius Mountains in Mohave County. The site has produced a wide array of sharp garnet crystals embedded in a light-colored rhyolite matrix.

The Washington-Duquesne area in the Patagonia Mountains is a place where garnets are common and are found as gangue rock resulting from local mining operations. The Empire Mine, patented by a Captain O’Connor in 1874, was originally worked by chloriders for the next several decades. Production included high-grade lead silver ore. The Duquesne Mining and Reduction Co. acquired the property in 1905. George Westinghouse, inventor of the railroad air-brake, served as the president, consolidating 84 patented lode claims including the Bonanza and Empire Mines. An aerial tramway was built to service the Pride of the West Mine to the mill and smelter at Washington Camp.

Andradite is named after the Brazilian mineralogist Josè Bonifácio de’Andrada e Silva, who first described its properties. Andradite, a calcium iron silicate that commonly occurs in contact metamorphic rock and impure limestone, is scattered throughout the tailings of the Empire Mine. These garnets appear dark-brownish green with adamantine luster and are stained black by oxide of manganese and iron. The green coloration is derived from the presence of chromium impurities. Some andradite crystals from this locality have been found up to 3 inches in diameter.

Stanley Butte in the Stanley district in Graham County, 25 miles south-southeast of the town of San Carlos, is another location for andradite sometimes appearing with grossular. At this locality andradite is found as massive material with green-tinted brown crystals up to 2 inches.

While many of the above localities were open to collecting garnets and other minerals and gemstones years ago, the transfer of land rights and titles to property have now made many of them off limits to visitation. It is best to contact local authorities ahead of time to better ascertain whether or not collecting is permissible.

- By William Ascarza Special to the Arizona Daily Star

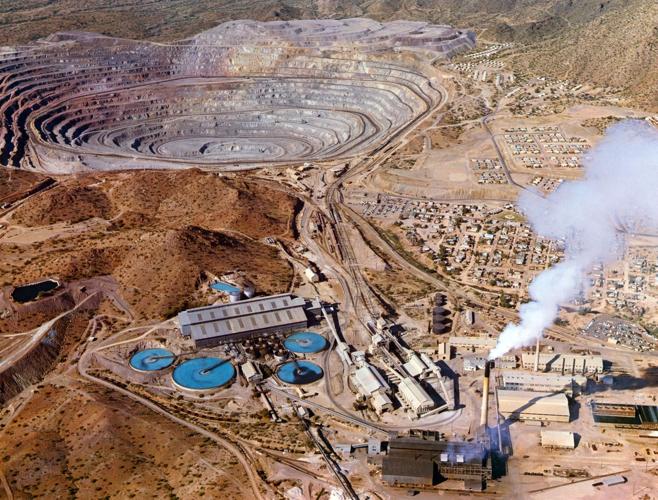

Ajo, in western Pima County 125 miles west of Tucson, has one of Arizona’s best-known porphyry copper deposits.

It enticed small mining operations by the San Francisco syndicate known as the American Mining and Trading Co. as early as the mid-19th century, though its silver chlorides on the surface were originally discovered by Spanish explorers seeking a more direct route to the Pacific.

The site’s remoteness and technological limitations made ore transport challenging. High-grade copper ore was transported by teams of oxcarts across several hundred miles of desert to San Diego, where it was loaded on ships destined to sail around Cape Horn to Wales for smelting.

Later ventures involving mining promoters A.J. Shotwell and John R. Boddie also failed to fully exploit the deposit. Both foolishly invested in a contraption known as the McGahan Vacuum Smelter, touted as having the ability to extract copper and valuable byproduct metals without water or fuel. The apparatus was marketed by a swindler, Fred L. McGahan, who absconded with the investors’ money.

In 1911, the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co., whose operation was principally out of Bisbee, took an option on 70 percent of the stock of the New Cornelia Copper Co. Geologist Ira Joralemon, mine manager John Campbell Greenway and metallurgist Louis D. Ricketts successfully built a leaching plant at Ajo with the capacity of processing 5,000 tons of ore a day. This advancement served as a prerequisite for the open-pit mining operations that would follow to fully exploit the New Cornelia ore body, composed of the disseminated copper sulfide minerals chalcopyrite and bornite.

Water to sustain the operations was found several miles north at Childs Siding. A rail line was extended from Ajo to connect with the Southern Pacific Railroad at Gila Bend, improving ore transport.

Ajo holds the distinction of being Arizona’s first open pit mining operation, having begun with the first removal of overburden in December 1916, followed by more aggressive earth movement the following year.

At the time, the ore averaged 3.66 percent with 86 cars of it having been shipped to the Douglas smelter. World War I increased the market price of copper to 25 cents a pound, covering the New Cornelia Copper Co.’s operating expenses while enabling it to pay its first dividends to its shareholders in November 1918.

Leaching of the carbonate ore also was initiated and was later processed by electrolysis for the production of pure copper cathodes, lasting until the ore was exhausted in 1930. A concentrator for treating the sulfide ore was completed in 1924, reaching a capacity of 16,000 tons of ore daily by 1936.

During the 1920s, a fleet of 18 steam locomotives served the pit. They operated on a 2 percent grade covering the 2¾-mile distance between the bottom of the pit and the primary gyratory crushers.

Phelps Dodge Co. acquired the Calumet and Arizona Copper Co. in 1931, later expanding the pit with the stripping of part of Arkansas Mountain, the site of the former Cardigan mining camp. Four 22.5-cubic-yard end-dump haul trucks performed this task, avoiding the high cost of track haulage. Electric shovels began to replace the old-time steam shovels with a total of nine in operation by 1939.

Diesel locomotives began operating at Ajo in 1945. The first ones included two units that arrived from Morenci. Steam locomotives reached their zenith in 1947 with 17 rod locomotives operating at the open pit. Soon thereafter they were replaced with a combination of trolley-electric and diesel-electric haulage transport, reducing costs that effectively reduced the cutoff point or minimum grade of the ore selected for processing from that of waste rock.

Prior to the erection of the $8 million Ajo smelter in 1950, concentrates from the open pit were transported to the Douglas smelter. Within three years, the mill was increased to a capacity of 30,000 tons.

Low copper prices and high operational costs in the mid-1980s indefinitely suspended mining activity at Ajo. It is estimated that 445.9 million tons of ore were mined since 1900 with production of over 3 million tons of copper, 463 tons of molybdenum, 1.56 million ounces of gold and 19.7 million ounces of silver.

There remains the opportunity for Ajo to yet again contribute to Arizona’s mining history . The economic potential appears favorable after Freeport-McMoRan’s recent assessment that Ajo contains sulfide ore reserves of 482 million short tons, averaging 0.40 percent copper and 0.010 percent molybdenum, 0.002 ounces of gold and 0.023 ounces of silver per ton.

With the right economic conditions, Ajo may once again become a thriving mining town.

- By William Ascarza For the Arizona Daily Star

Like many copper mining towns in Arizona, Ray was booming in its heyday.

Ray — about 90 miles north of Tucson and 80 miles east of Phoenix — was the largest town in Pinal County in 1914, with a population of 5,000.

Located at the foothills of the Dripping Spring Mountains on Mineral Creek, it had a newspaper, the Copper Camp, and was the headquarters for the Valley Bank and Miners-Merchants Bank.