BARRY GOLDWATER RANGE —

It’s hard to reach these remote border barriers even from the U.S. side.

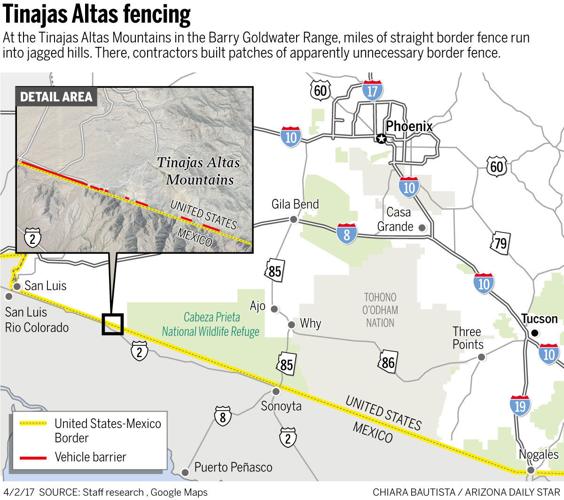

Photographer Mike Christy and I drove four hours from Tucson on Wednesday, including an hour over sandy, rocky roads south of Wellton, to reach the place where the U.S.-Mexico border crosses the Tinajas Altas Mountains.

About a half-hour after we arrived and started working there, a stern Border Patrol agent sped up to us, leaving clouds of dust, to say we had to leave. Although we had the necessary permits to be in the range, this wasn’t a public road.

Early the next morning, we tried an adjacent route, a “tertiary public road” the map called it, to reach a few nearby stretches of border fence built across the base of mountains. We got stuck in the sand twice before escaping by digging with our hands, wedging rocks under the wheels and pushing.

Finally, we reached our destination, a series of apparently senseless fences.

In 2007, Boeing got a $122.2 million contract and started work on 32 miles of border fence along the southern edge of this military reserve.

Most of the fence runs straight and true across the flat desert. It helped cut apprehensions by 90 percent in the Border Patrol’s Yuma Sector between 2005 and 2016.

But at the mountains, the builders put six shorter stretches of 16- to 18-foot-high vehicle and pedestrian fence in small basins at the foot of the sharp hills, barriers that measure anywhere from 240 to 520 paces long. Two of them could be justified because washes run south to north through those stretches and could be used for vehicle traffic. But four of these fences, measuring more than a half mile together, make no sense.

They’re senseless because as hard as it is to reach them from the north, it’s impossible to drive to them from the south. The jagged peaks to the south are steep and rocky with no passes to drive through. The only way over would be by foot, yet these fences are easy to walk around. You just walk over a few rocks and pass by.

At about $3.8 million per mile for all 32 miles on the Goldwater range, these four remote, decorative fences probably cost at least $2 million.

And that’s nothing compared to what we’re about to waste.

The Trump administration has begun requesting contractor proposals and congressional funding for a massive border wall, fulfilling one of the president’s top campaign promises. No, he’s not getting the money from Mexico as promised in the campaign.

The estimate he and congressional Republicans have made is that a barrier across the whole, 2,000-mile border would cost at least $12 billion, and other analyses suggest it could cost $25 billion or more.

But even that may be low. Last week, the administration asked Congress for $1 billion to pay for just 48 miles of new border barriers and 14 miles of replacement fencing.

What they’re asking us to sacrifice to pay for these border fences is severe. The administration sent to Congress last week proposals for $18 billion in budget cuts to help pay for the wall. The sacrifices come in painful pieces like $1.2 billion cut from medical research, and $1.5 billion from community development block grants. That amounts to a 50 percent cut to the federal grant program that underwrites, among other services, $450,000 for home repairs for poor people in Pima County and programs for the homeless in Tucson.

All this money and these sacrifices are being requested to build new barriers that are — despite the president’s campaign rhetoric — of doubtful need.

The border went through a building boom in the years 2006-2010: About 650 miles of barriers went up. In 2008, Congress changed a law that had demanded more border barriers, instead allowing the DHS to build barriers where needed. The department did.

This was a lucrative business for some government contractors, who were paid more than $2.3 billion for the jobs. Suddenly, most of the areas where border barriers could work had them.

As a team of Star reporters and photographers showed last year, after visiting much of the 2,000-mile border for a series called “Beyond the Wall,” most of the areas left without barriers have physical obstacles — mountains, rivers and canyons.

They’re places like the Tinajas Altas. Ten years ago, we were already wasting money there.

Now, business interests and political pressures are in confluence again, pushing for taxpayer spending on more border barriers. But the Border Patrol agents’ union, which enthusiastically endorsed and helped candidate Trump, is trying to pump the brakes on the movement toward a big expensive wall.

In a March 16 statement, the National Border Patrol Council thanked Trump for proposing in his budget to increase funding for hiring new agents but said, “Tough choices will have to be made as to which investments will have the greatest impact on border security and this includes funding for ‘the wall.’ ”

It was a subtle message to the administration that benefited so much from the union’s political support.

Union President Brandon Judd, who long worked in the Tucson Sector and has had close contacts with the Trump administration, put it this way in a March 22 hearing of the U.S. Senate Homeland Security and Government Affairs Committee:

“We don’t need a great wall of the United States. We don’t need 2,000 miles of border wall. I will tell you, however, that a wall in strategic locations is absolutely necessary.”

What the union seems to be requesting is that more money and emphasis be put on hiring agents rather than building a symbolic wall. They’re right. Lately, the agency can’t hire fast enough to replace those who leave. Spending too much on a barrier and too little on people could mean there is no one to arrest those who inevitably get over, under or around any new barriers. We can hire them without cutting the social programs we depend on, but we can’t build needless border walls, too.

On Thursday morning, photographer Christy and I took a public road to find the border fence but planned on working fast because we figured agents would show up to check on us and maybe try to eject us within a half hour, as they had the day before. We figured we’d trip a sensor, agents would come, and we’d have to argue for our right to stay.

But the minutes passed, then more than an hour, and eventually our work was done. We decided to leave. Having got stuck in the sand of the tertiary public road, we decided not to go back that way but to take the “official use only” road out. We planned on explaining to the agents who we figured would stop us that we were leaving the area and just wanted to avoid getting stuck again.

But we drove out, past the senseless fences, alone. Nobody was around to stop us.