The "beautiful wall" Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump envisions would be 35 to 40 feet tall and 1,000 miles long, covering roughly half of the U.S.-Mexico border. Along the rest, natural barriers like rivers and mountains would continue to divide the two countries.

Trump estimates the project would cost $12 billion — although one estimate puts the pricetag as high as $25 billion. Whatever the amount, he says he'll make Mexico pay by confiscating money its residents living here send back to their families.

It's tough to find anyone living along the borderlands — even those who agree with Trump that the international line is not secure — who thinks a wall is the solution. Instead, many border residents want fencing that makes sense for their area, agents and surveillance technology closer to the border, and a way for migrants to come here legally and work.

Gerardo Vasquez, 26, and his daughter, Tabata Abigail, 3, play in the surf on the Mexican side of the border. Signs and Border Patrol agents keep people from getting close to the fence on the U.S. side. Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star

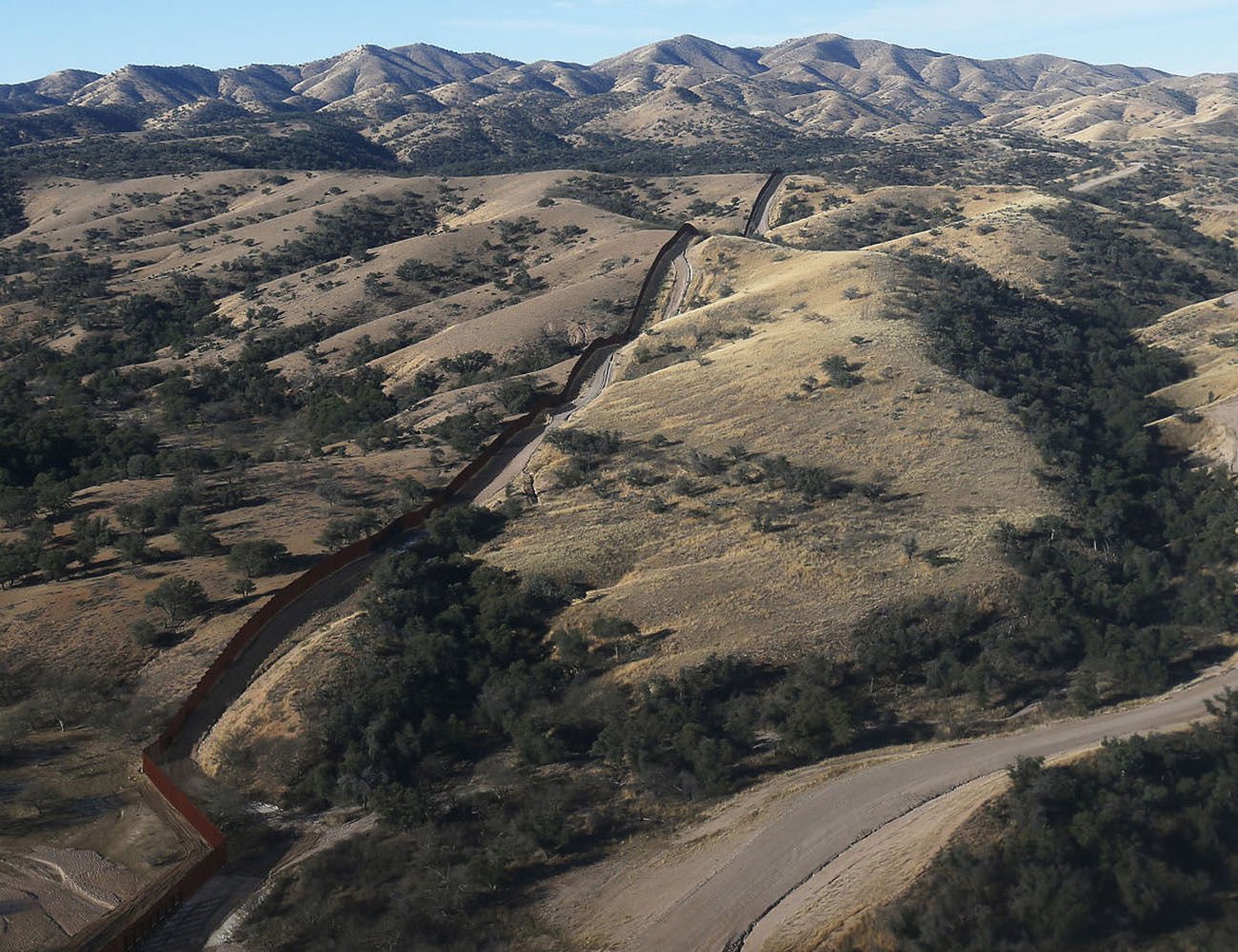

More than half of the 1,000 miles where Trump wants to build a wall are already fenced with a hodgepodge of steel plating, heavy-duty mesh, towering metallic slats and barbed wire. In remote areas, where the Border Patrol wants to stop cars loaded with illegal goods, chest-high vehicle barriers line the border. In cities, where crossers try to scale the fence and run, the poles are high and smooth.

Trump has given few details about his plan, but his August 2015 reference to it as being fashioned from "beautiful nice precast plank" indicate a solid wall — one that could take the place of the various fences that divide the border now.

We've been here before. In 2006, six Arizona Daily Star journalists traveled the entire U.S.-Mexico border, analyzing the feasibility of the 700-mile, double-layer fence proposed then through the federal Secure Fence Act. The team's conclusion was that a continuous fence would not work — natural barriers like rivers, canyons, mountains and shifting sand made fencing the entire border impossible.

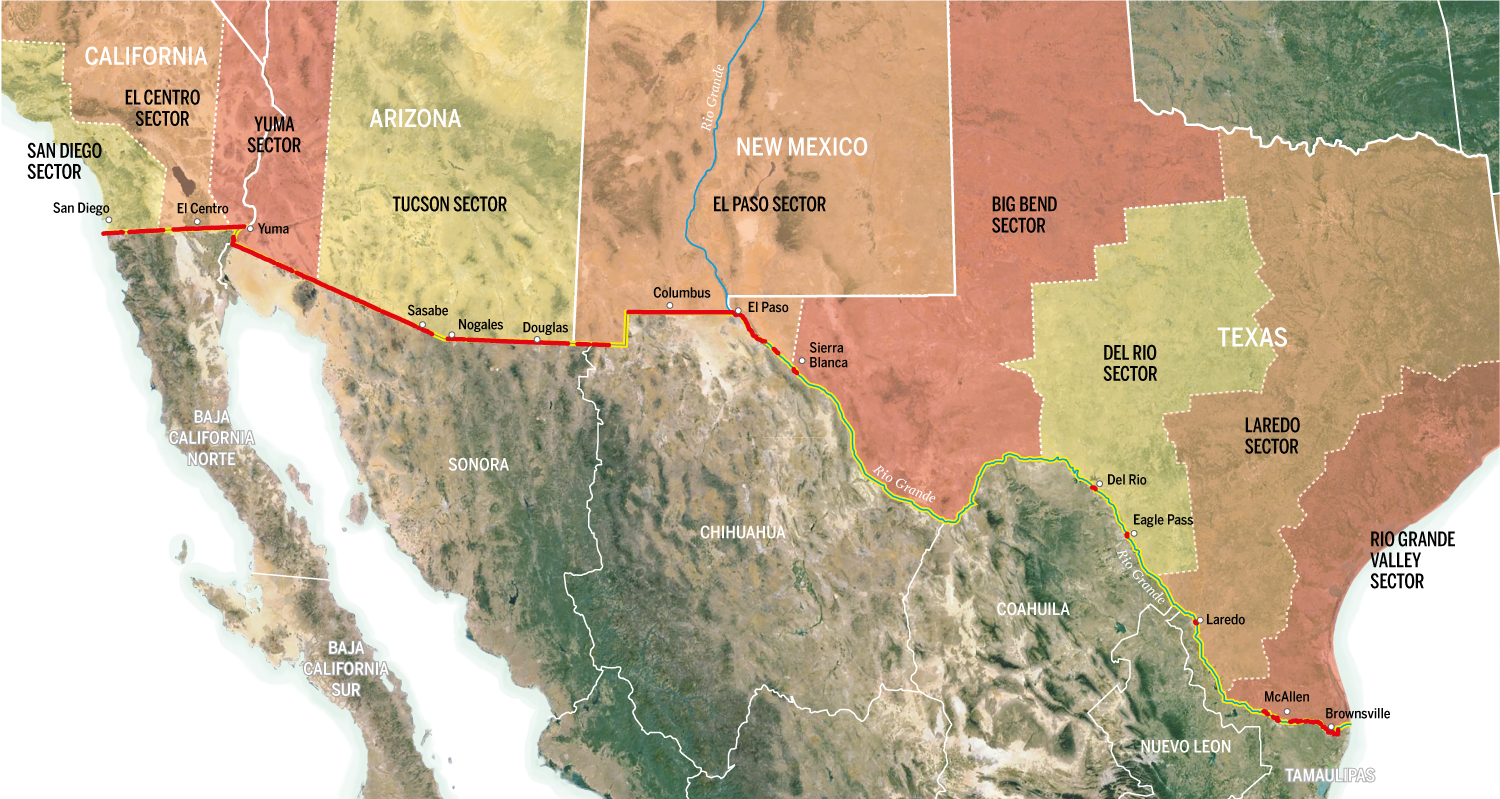

MAP OF U.S. MEXICO BORDER

RED LINE = AREAS FENCED

Drag to move along the border. Tap dots to learn more about key spots along the way.

Congress tweaked the law in 2008, requiring the Department of Homeland Security to build fence where and however the agency felt it was needed.

This spring, with Trump's "build the wall" message resonating so powerfully that he became the presumptive Republican presidential nominee, a new team of Star reporters went back to the border. Their goal: to go beyond the political rhetoric and talk with people who live and work along the international line.

Much is different after a decade. The border now has 703 miles of barriers — 653 miles of linear fence, plus a double or triple layer along 50 of those miles — most of it built in the last decade at a cost of $2.3 billion.

And that's not including the roughly $55 million a year Customs and Border Protection spends to maintain and repair the fence, along with associated roads, lighting and other infrastructure.

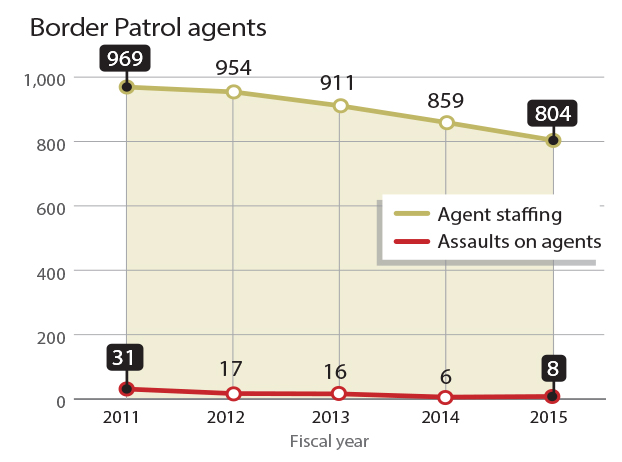

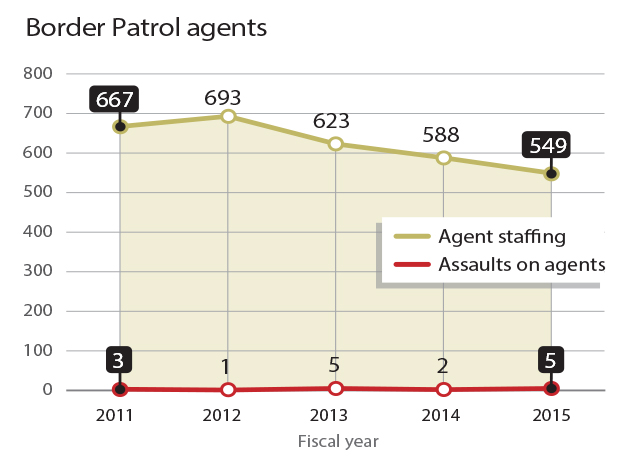

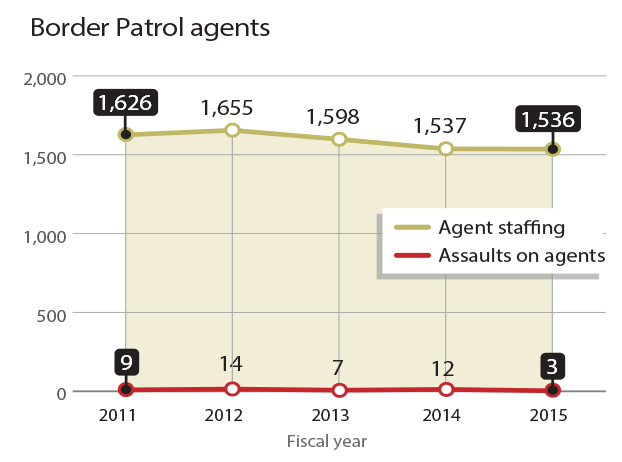

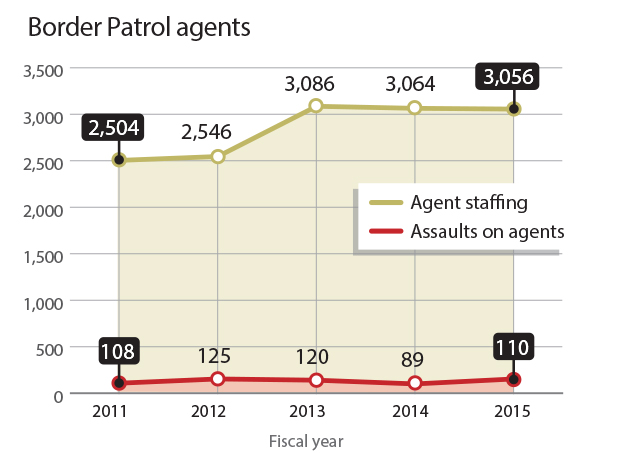

As the fence went up, the number of Border Patrol agents jumped from roughly 12,000 to 20,000 and the agency’s annual budget almost doubled, to nearly $4 billion. Thousands of ground sensors, dozens of camera towers, helicopters, drones and blimps now keep watch 24 hours a day.

Border Patrol apprehensions are a third of what they were a decade ago and those arrested are more likely to be prosecuted. More Mexicans are leaving than coming for the first time since 2009.

It's impossible to say how much of that is due to enforcement, since the drop coincided with an improved economy in Mexico and the worst financial conditions in the United States since the Great Depression.

Still, people come.

Handprints dot the steel fence poles from crossers who scale it; thousands of etchings indicate repairs made after trucks barreled through; wooden ladders are piled on the ground.

On a series of border trips this spring and summer, four Star reporters and two photographers talked with about 100 residents on both sides of the border along with ranchers, business owners, environmentalists, Border Patrol agents and researchers about the impact and feasibility of a solid wall.

The team found that some stretches the Border Patrol considered 10 years ago to be "unfenceable" — a canyon in California, for example, and shifting sands near Yuma — were, indeed, fenced, but at great financial and environmental costs.

BORDER PATROL SOUTHWEST SECTORS

With the changes in border enforcement in the past decade, the Star team determined that Trump's proposed "great, great wall" is already built in some ways — and building the rest is either not needed or not feasible:

• The jagged mountains, deep canyons, and winding rivers that remain unfenced pose a more effective natural barrier than humans could build.

• Illegal traffic has shifted to rugged areas where building a fence would be tremendously expensive and would slow smugglers and border down only by seconds on a multi-day journey.

• In Texas, the state with the least fencing, the border runs along private land. Forcing landowners to sell would lead to drawn out and costly lawsuits.

Beyond the logistical challenges, even the tallest wall would not solve the most serious problems at our border:

• Hard drugs, a chief reason Trump said he wants a wall, mostly come through the southern border's 328 legal ports of entry. Those crossing stations see $500 billion in trade every year and are used by many of the 15 million border residents in the United States and Mexico.

• A wall wouldn’t stop the current wave of Central American families and children who turn themselves in rather than evade capture.

• It wouldn't keep out people who overstay their visas — a group that makes up about half of the unauthorized population in the United States.

In short, the fence we already have has done most everything a fence can do.

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARIZONA

ARIZONA NEW MEXICO

NEW MEXICO TEXAS

TEXAS