SAN DIEGO — Once a canyon created over thousands of years, Smuggler’s Gulch is now a massive earthen berm with two border fences and a road on top — the result of landscape alterations that cost taxpayers millions of dollars.

The federal government lopped off the tops of two mesas in 2008 and filled what was a 230-foot chasm with enough dirt to pack 72,000 dump trucks.

Smuggler’s Gulch, two miles east of the Pacific Ocean at the southernmost tip of San Diego County, is an extreme example of the challenges involved in fencing the entire U.S.-Mexico border.

Federal officials wanted the gulch filled to enhance the security of the border and the safety of U.S. personnel. The department expedited the project through the Real ID Act, which Congress passed in 2005. The law allows the federal government to suspend all laws impeding the construction of border barriers in the name of national security.

2008: After 12 years of planning, environmental reviews and legal challenges, workers began filling Smuggler’s Gulch to make way for a border fence.

In other words, when the federal government builds fences and other barriers along the border, it does not have to follow the Endangered Species Act, the Clean Water Act, the National Environmental Policy Act or the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, among others.

Directives to build border barriers often come from politicians who are not familiar with the border’s craggy canyons and meandering lines, nor with its natural heritage and ecology. The Border Patrol, which carries out the directives, struggles to prevent illegal activity on the border while working with public land managers trying to protect natural habitat.

The agency also has funded projects to mitigate damage caused by the fence in California and other border states.

In Arizona, Organ Pipe Cactus National is restoring 230 miles of roads. Also, San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge built a fish barrier to keep non-native species from entering the refuge and threatening native populations.

Many of the headline-generating environmental projects on the border have been in California, but the issues are similar all along the line. Fencing added in the last decade has been devastating to wildlife migration, to the natural flow of water after a storm, and to plant life along the border, environmental advocates say. There has been flooding, soil erosion and increased roadkill from night lighting and vehicle traffic, says the Sky Island Alliance, a Tucson-based conservation group.

Affected wildlife include ocelots and jaguars, migratory birds and bats, black bears, desert bighorn sheep, white-nose coati — all dependent on the ability to move back and forth across the borderlands.

“Barriers can block passage for animals in search of food, water or mates, for migration, or in response to drought and fire,” says Jessica A. Moreno, conservation, outreach and development manager for the Sky Island Alliance. “This infrastructure also pushes human activity to the last remaining open areas — rugged and wild habitat and wilderness that are now seeing more human impacts from border activities such as a lighting, roads, trash and noise.”

The Yaqui chub fish, for example, is endangered and has little habitat left. Why does that matter to humans? Because the chub eats mosquitoes that bring viruses into the United States.

“We are all connected in one way or another,” says Bill Radke, manager of the San Bernardino Wildlife Refuge. “To not see that, to live with dire consequences of that, it’s not something that we should be headed for.”

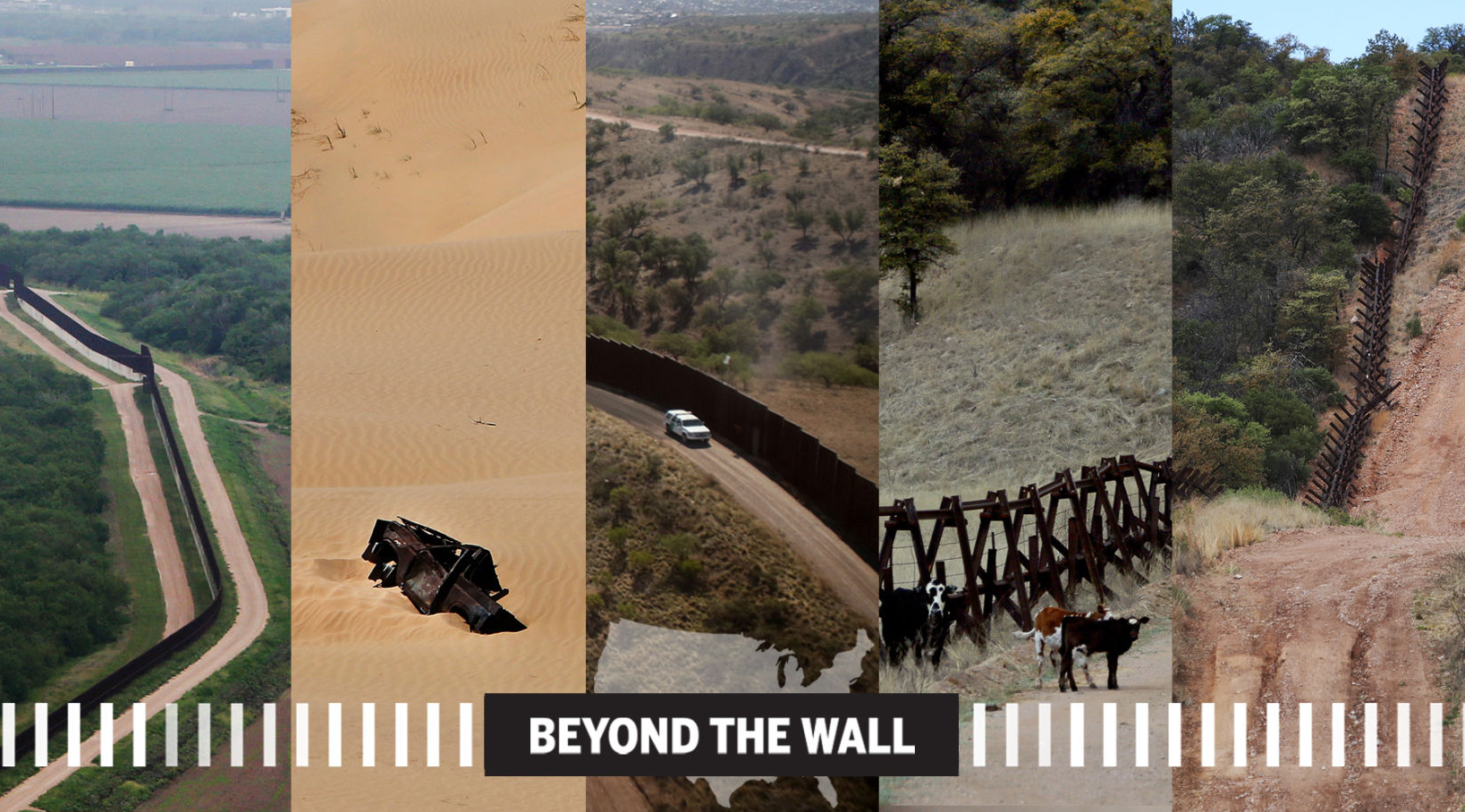

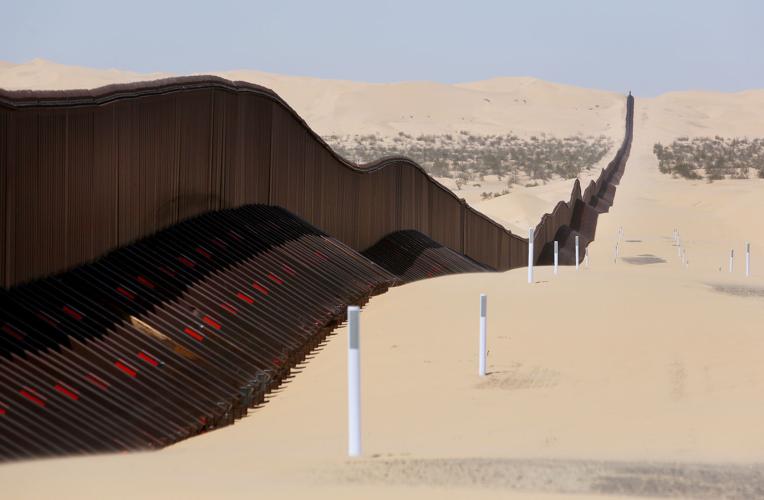

THE CALIFORNIA BORDER: SAN DIEGO, EL CENTRO AND YUMA SECTORS

Marie Teresa Fernandez has been documenting the U.S.-Mexico border fence on both sides for 15 years.

• 140.4 total border miles

• 100.6 pedestrian miles

• 15.1 vehicle barrier miles

• 18 percent unfenced

• The San Ysidro Port of Entry between California and Tijuana, Mexico, is the busiest land border crossing in the Western Hemisphere and is undergoing an expansion. It typically handles 50,000 northbound vehicles and 25,000 northbound pedestrians per day.

• Of its 115.7 linear miles of California’s border with Mexico, 87 percent is “pedestrian fencing” that prevents people from crossing on foot.

• More hard drugs are seized at ports of entry overseen by the San Diego field office than any other along the Southwestern border.

• In one particularly rugged area of California called the Otay Mountain Wilderness Area, installing border fencing cost $16 million per mile.

INTERACTIVE MAP OF CALIFORNIA-MEXICO BORDER

RED LINE = FENCED AREAS

Drag to move along the border. Tap dots to learn more about key spots along the way.

No more car chases

Before Smuggler’s Gulch was filled in, the San Diego Audubon Society tried to stop the project with a lawsuit that predicted disastrous effects on the fragile Tijuana Estuary, the largest coastal wetland in Southern California.

Storm runoff from Mexico runs north through Smuggler’s Gulch and ends up in the estuary — and eventually in the Pacific Ocean.

The estuary is considered an essential breeding, feeding and nesting ground and key stopover point for more than 370 species of migratory and native birds, including six endangered species. But the lawsuit was tossed out of federal court because of the Real ID Act.

“It was really spectacular with beautiful geology,” says Jim Peugh, conservation manager for the San Diego Audubon Society. “Everyone expected they would screw it up — and they did.”

Border infrastructure is one more impact on the estuary, along with agriculture, the military and a huge population boom in Tijuana, now home to an estimated 2.5 million people.

A culvert built between 2008 and 2010 in Smuggler’s Gulch carries water from Tijuana, Mexico, under the U.S.-Mexico border fence.

Carol Kimzey’s ranch is across the street from Smuggler’s Gulch. A decade ago, she told the Star she was skeptical about plans to fill the canyon. She worried that flooding at her home would get worse.

But her skepticism is, for the most part, gone. She no longer sees vehicles picking people up at night or people running through. She no longer hears car chases like the one that left a vehicle upside down in her front yard, the men inside jumping out and fleeing.

Carol Kimzey, ranch owner.

“There used to be hordes of 28 to 30 people, it sounded like an earthquake,” she says. “Now, I can’t remember the last time I’ve seen one.”

She gets wistful remembering her drives up to the top of the canyon, where she’d park and take in a view that included both her ranch and Mexico.

“I do miss that,” she says.

Her neighbor, James “Butch” Martin Jr., liked the old Smuggler’s Gulch. The 54-year-old retiree says he never minded the border crossers who passed through. Most were just looking for work and many found it at nearby ranches, he says.

He worries that the earthen berm could become unstable with heavy rains.

When that thing blows, it’s going to take us all out,” he says.

Water that once ran through the canyon is now redirected through a man-made culvert. That pushes runoff, including trash and sediment, faster and farther into the fragile Tijuana River Estuary, says University of California-San Diego professor Oscar Romo, who runs the binational nonprofit conservation group Alter Terra.

“It took 2 to 4 million years for nature to create this basin,” Romo says as he walks alongside the culvert. “Now all of that is gone.”

Oscar Romo, professor in urban studies and planning at the University of California at San Diego.

As the only remaining estuary in Southern California, the Tijuana Estuary’s value is incalculable, he says.

“We treasure it. However, we are trashing it with these pieces of infrastructure that are not helping, that are not well-designed, that are generating heavy impacts on the natural resources of this area.”

Customs and Border Protection spent $58 million to fill in Smuggler’s Gulch, plus build 3.5 miles of secondary fencing, roads and lighting in the San Diego Sector. The sector includes 60 miles of border and more than three quarters of it — 46 miles — has some type of fencing.

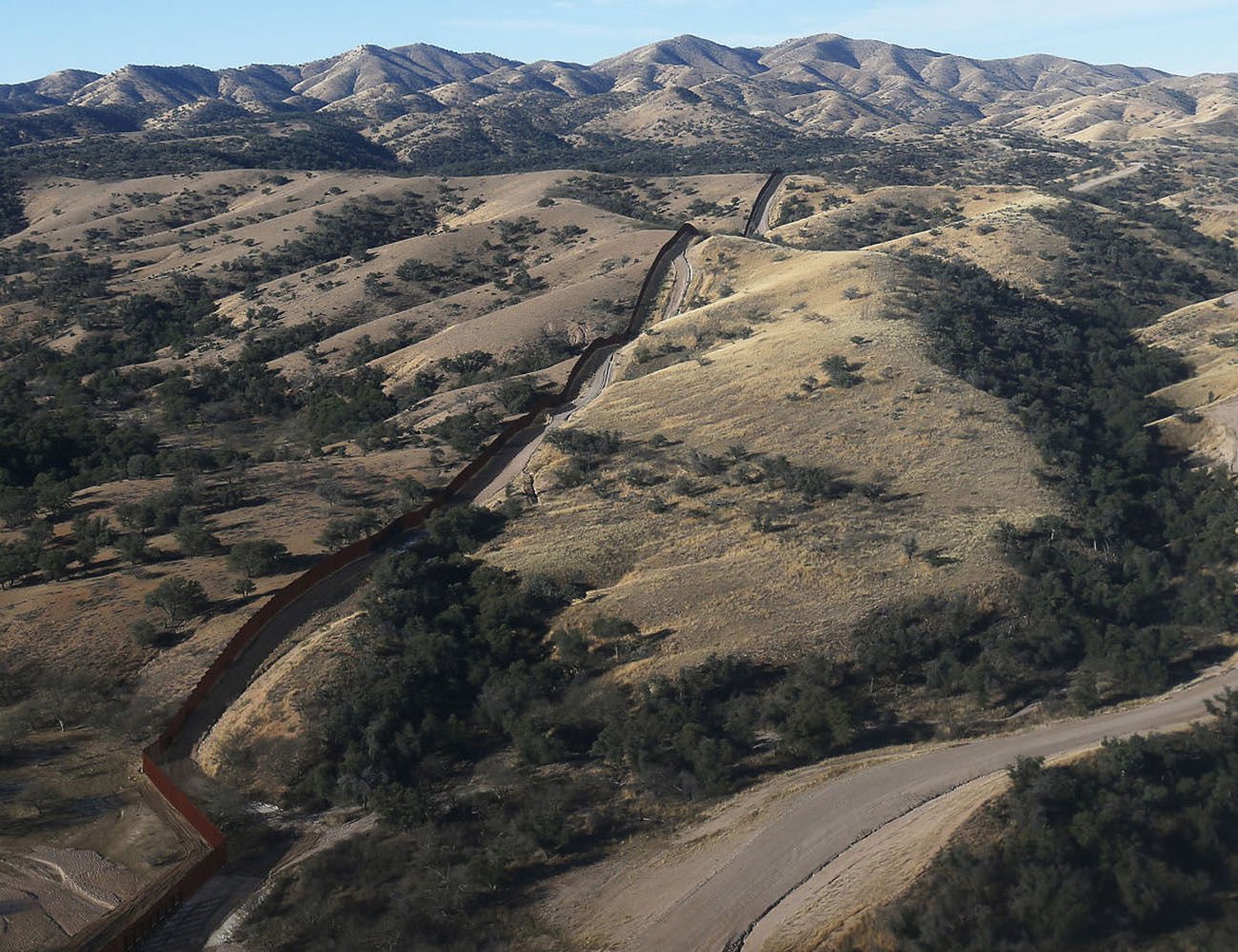

A decade ago, 60 percent of the sector was fenced. Border Patrol officials believed at the time that certain parts of the sector, like the Otay Mountain Wilderness, did not need a fence because of their harsh terrain.

“There’s no reason to disrupt the land when the land itself is a physical barrier,” Richard Kite, then spokesman for the Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector, told the Star in 2006.

But three years later, the Department of Homeland Security completed a barrier in the Otay Mountain Wilderness Area — 3.6 miles of primary fencing and more than five miles of access road.

The rugged terrain required grading and leveling a federally designated wilderness area. That meant cutting down Tecate cypress trees and scraping off deep root systems of ground cover that held topsoil and moisture in place, says Jill Holslin, a Tijuana resident who maintains a blog about the borderlands called ”At the Edges.”

“The problem out there now is dryness and the absence of native plants,” Holslin says. When it rains, “there’s nothing to hold the soil in place. There’s also been an invasion of a parasitic plant that is taking advantage of conditions there, sapping whatever moisture there is in the soil.”

The best move to prevent more damage is to overturn Section 102 of Real ID Act, Holslin says.

A sediment basin built in 2005 catches debris and trash coming downhill from Tijuana, Mexico. With an increase in development in Tijuana, more trash flows downward when it rains.

It has been three years since the government has used the act to grant waivers of federal laws in the name of border security, but it still has the power to do so, says Dinah Bear, former chief lawyer for the Council on Environmental Quality under four different U.S. presidents and now a Tucson resident. Lawsuits challenging the constitutionality of Real ID’s waivers so far have failed.

“They’ve taken away the mechanism for the public to fight back,” Holslin says. Area conservation groups like the Audubon Society and Wildcoast are the ones that understand the topography, she says. “You have to have their professional input in these processes and you’ve literally taken their voice away.”

But the voice of people who live on the border and the safety of those who protect it should count, too, says Dan Russell, 73, a retired firefighter from San Diego.

The border is “wide open, it’s not secure,” Russell says during one of his regular visits to the border community of Campo, California. “The Trump wall is a good example of a secure border. What we have now isn’t stopping people. Seven years ago they crawled underneath it, they jumped Border Patrol Agent Robert Rosas and shot him in the neck and killed him. Just four miles east of here.”

Multilayer deterrent

Chris Peregrin, manager of the Tijuana River National Estuary Research Reserve and manager of Border Field State Park in San Diego.

As he drives along a road between the double fencing in the U.S. Border Patrol’s San Diego Sector, agent James Nielsen points to grates in the fence that let water through. It’s a complicated setup, letting water drain without creating tunnels smugglers can use.

Illegal tunnels have been found here, he says, motioning toward a building on the Mexican side where the floor was removed and turned into an elevator to a sophisticated cross-border tunnel that included a rail system and lights.

The sector has almost 2,400 agents, up 42 percent from a decade ago. Apprehensions of people trying to slip across the border have dropped during that same time, by nearly 80 percent. Eight months into this fiscal year, there have been nearly 21,000 such apprehensions. Ten years ago the number topped 100,000 per year.

At the same time, seizures of harder drugs like cocaine and heroin have gone up, creating concerns about more sinister criminal activity.

Some San Diego and Imperial Beach residents refer to the border barrier near them as a “triple fence” because of chain link property fencing in some areas in front of the double line of fencing. Having those extra fences gives the Border Patrol more time, Nielsen says. He says the more deterrents and obstacles at the border, the less likely someone will make it across.

“When they built the fence, they said that one of the environmental benefits was that the Border Patrol would no longer need the spider web of roads they used to look for border crossers,” says Peugh of the San Diego Audubon Society.

“They said they would get rid of them and restore the damaged habitat. I looked at an aerial photo of the river valley and estuary recently. I do not have a pre-triple-fence photo to compare, but there is still a spider web of roads.”

One of the agencies working to mitigate damage to habitat in the area is the state of California, which operates the Tijuana River National Estuary and Research Park. The state works with the Border Patrol to minimize roads and disruption of the natural ecosystem, says Chris Peregrin, an environmental scientist who is manager of the park.

The state’s mission is to restore the natural functions of the area. Yet, in an example of how their missions differ, the Border Patrol doesn’t want plants near the border growing too high because people can hide in them.

The Tijuana Estuary, covering 1,700 square miles, is one of the most significant coastal wetlands in Southern California. It runs right into the Pacific Ocean at Imperial Beach in San Diego.

Wildlife blocked

Environmental advocates point to numerous spots along the border where fencing has gone up without regard to existing laws. The San Pedro River and the San Pedro Riparian National Conservation Area in Arizona, just west of Naco, is a biologically diverse area and home to one of the last free-flowing rivers in the Southwest.

“It’s a beautiful riparian area that’s the lifeblood of the desert,” U.S. Border Patrol sector spokesman John Lawson says.

The river, which flows south to north across the border, is less than a mile wide. Vehicle barriers across it let large wildlife and water flow freely, although the river is dry part of the year.

As he walks in the riverbed along the border, Lawson points out the paw prints of a black bear that indicate the animal has come north from Mexico. Moments later, a deer crosses the Normandy-style criss-crossed posts of the vehicle barrier and is later seen further north where the San Pedro is flowing.

Barriers like these are the only place where large wildlife can regularly pass along a 47-mile stretch of border running east from the Huachuca Mountains. The rest of that stretch of border has pedestrian fencing that’s impenetrable to large wildlife, though some areas have gates the Border Patrol opens during monsoon season.

Just east of the river is a compound that belongs to Glenn Spencer, president and founder of the nongovernment American Border Patrol. Spencer is a retired systems engineer whose group has developed technology, including sensors in the ground, to detect illegal activity.

Before the U.S. Department of Homeland Security put up 18-foot fencing behind his home, Spencer says it was like the “Wild West.” There was so much illegal activity, including cars driven across his property by drug smugglers, that he was afraid to walk his dogs.

“Now it’s like a gated community,” he says.

Spencer dismisses environmental arguments against the high fence behind his home.

“Rabbits run through it all the time. The fence design allows certain critters to get through,” he says. “Javelina and deer are limited to the riparian area around the river, but look at Google Earth. They have plenty of habitat in Mexico.”

The Sierra Club and others tried to stop six miles of 18-foot-high bollard-style pedestrian fencing from going up in the San Pedro area, but they failed because of the Real ID Act.

Since then, wildlife such as mule deer and javelina have been unable to access habitat in Mexico, says Dan Millis, borderlands coordinator for the Sierra Club’s Grand Canyon chapter in Tucson. Millis refers to the fencing as a wall, since wildlife cannot pass through.

“Every day wildlife is coming up to the wall and turning around. I saw a doe and two fawns at San Pedro. They walked up to the wall and took a look — they looked for a way to cross and came back,” Millis says. “They need to migrate and need to get up and down in elevation to survive. The border is blocking their ability to do that and is a threat to their survival.”

A deer passes through from Mexico into the United States through the vehicle barrier or "Normandy" type fencing in the San Pedro River National Conservation Area inside the Coronado National Memorial park in Arizona. The vehicle barriers are used so that wildlife can cross freely.

Border barriers create problems for desert bighorn sheep and pygmy owls, University of Arizona researchers found in a 2009 study published in the journal Conservation Biology. The fence divided habitats and put bighorn at risk for inbreeding in a smaller gene pool, the study says.

“It takes a long time for wildlife to adapt to this kind of thing, and by the time they adapt it could be too late,” Millis says.

Intermittent fencing does not prevent humans from illegally crossing the border, but it does restrict the movement of puma and coati in Arizona, says a study conducted by British researchers and published in the journal Plos One in 2014.

That same study found that every 1,000 unauthorized immigrants crossing an international boundary generates 110 pounds of litter, 11 campfires and disturbs habitat of plants and animals.

Of concern to many wildlife advocates is an adult male jaguar dubbed “El Jefe” that was photographed by a remote camera 118 times over 34 months in the Santa Rita Mountains southeast of Tucson.

Even after the federally funded research by the UA and the U.S. Geological Survey ended last June, El Jefe — the only known wild jaguar in the United States — continued to show up in photos regularly through mid-October of last year.

Researchers speculate the jaguar might have gone to Mexico to breed, signifying the need for continued wildlife corridors for larger animals along the border.

VOICES FROM THE CALIFORNIA BORDER

Value of interaction

When Donald Trump and his supporters talk about building a solid border wall, it shows how little they understand about life along it, many border residents and environmentalists say.

“In my mind, building a wall means giving up on our homeland — severing the very tie that nourishes our people, culture, wildlife, and land,” says Moreno of the Sky Island Alliance. “We believe that border security should equally value the very homeland we are trying to protect: the clean, drinkable water, clean air and abundant wildlife that provide the quality of life we enjoy in our borderland communities.”

In 2011, the Sky Island Alliance commissioned a nationwide survey that found 64 percent of Americans oppose or strongly oppose waiving laws along the border to build infrastructure.

And a wall along the whole border would further complicate efforts to work with Mexico on issues that affect both sides, like pollution and water quality, says Fay Crevoshay, policy director for Wildcoast, a conservation group based in Imperial Beach, California.

Heavy rains that cause runoff from Tijuana regularly close beaches near the border. A solid wall would only make that worse, Crevoshay says.

“We should harness the possibilities of interaction between the two countries,” she says. “There is no one-sided solution to problems like pollution. ... We need each other.”

Slice of border life

Beyond the Wall: 10 years later, nothing at border park is the same

Star reporter returns to Friendship ParkPhotos: California and the Mexican border

Beyond the Wall: California border with Mexico in photos.

EXPLORE BY STATE

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARIZONA

ARIZONA NEW MEXICO

NEW MEXICO TEXAS

TEXAS