IMPERIAL BEACH, CALIF. — In the decade since I helped travel the U.S.-Mexico border for the Arizona Daily Star, a lot has changed — nowhere more noticeably than its far-western point.

The U.S. Border Patrol calls the spot Friendship Circle, though it’s known to locals as Friendship Park. One thing that’s not in dispute — over the past 10 years, gestures of friendship there have been increasingly restricted.

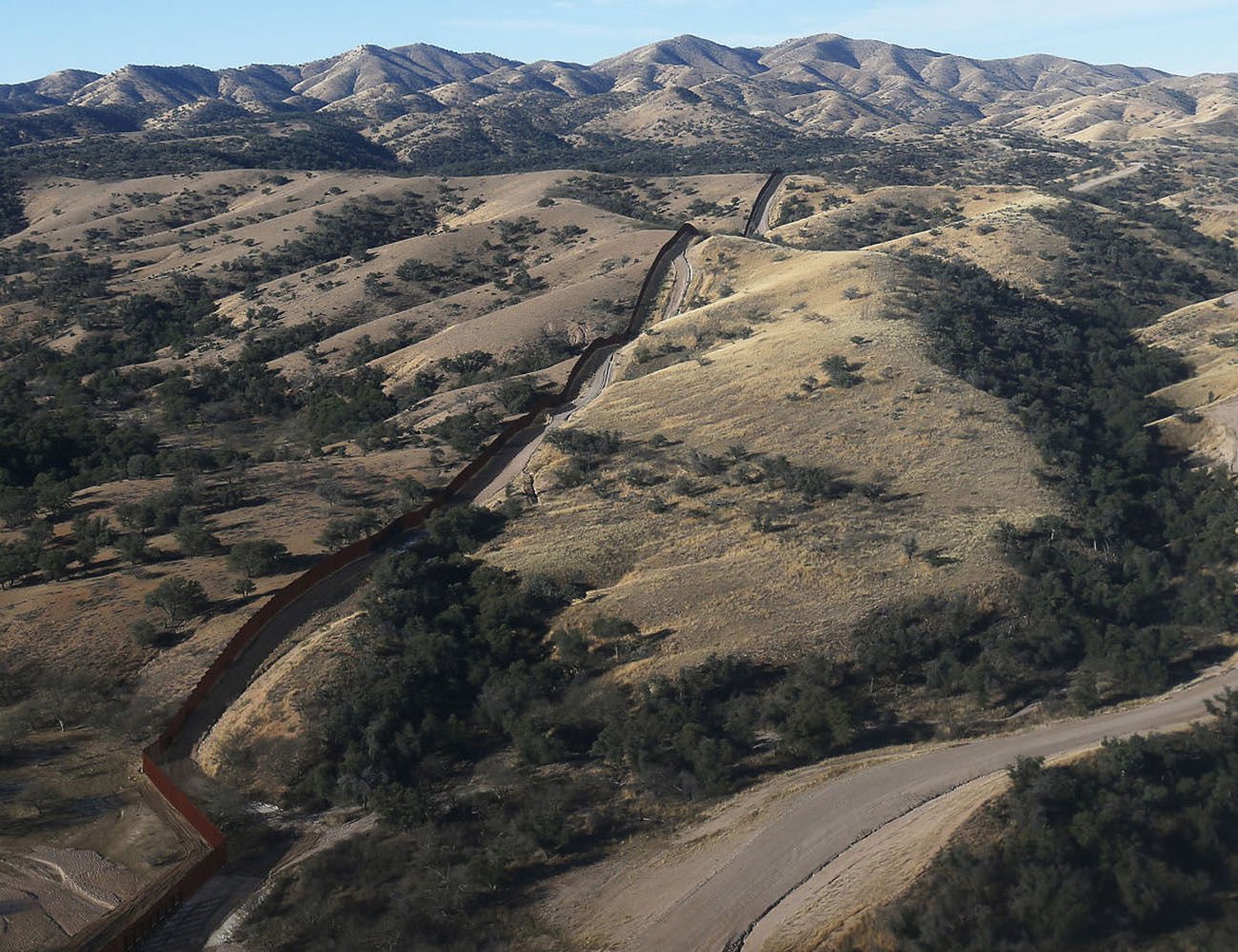

In July 2006 I drove the curving road into Border Field State Park in Imperial Beach, California, with then-Star photographer James Gregg. I was struck by the eerie quiet of the park and by the view — a fence atop a hill dividing two countries, cutting across a vast beach and stretching into the ocean.

At the summit of a hill called Monument Mesa was half of a paved circle — the other half is in Mexico. In the middle was a polished marble U.S. border “monument” obelisk marking the line set under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo at the end of the U.S.-Mexico War. A mesh fence divided the circle in half.

Then-first lady Pat Nixon planted a tree during the 1971 dedication of Border Field State Park and symbolically cut some of the fence. She has been reported as saying that, perhaps in the future, there would be no need for such a barrier.

When we visited in 2006, James struck up a conversation with 13-year-old Gerardo Daniel Cruz from Rosarito, Mexico. He was standing on the Mexican side and talked about how his school’s field trips to the U.S. had stopped after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

When Gerardo put his right hand up to the metal fence, pushed his fingers through and gripped the bars, James snapped the photo that became the cover image for our border project.

2006: Gerardo Daniel Cruz, 13, rests his hand on the mesh fencing that separates Tijuana, Mexico, form Border Field State Park in San Ysidro, Calif.

Now I’m back at Border Field State Park, this time with Star photographer Mamta Popat.

Flooding prevents cars from reaching the main park, so we leave the car and walk a little more than a mile, trudging through patches of swamplike terrain. We then climb the hill to see the border.

It’s still quiet, and more beautiful than I remembered, with a light breeze coming off the ocean, palm trees and purple flowers dotting the landscape. A Border Patrol agent sits in a car just above the beach.

A “no trespassing” sign prohibits the public from walking on the beach immediately in front of the rust-colored steel border fence posts that stretch into the ocean. We see activity on the beach in Playas de Tijuana on the Mexican side, and I notice a lot more tall apartment and condominium buildings than 10 years ago. A group of people standing on the Mexican side waves at us. We wave back.

Further up the hill, we find Friendship Park.

Where there once was one fence, now there are two, both new, running parallel to each another. The federal government has annexed the park from the state. The metal fence that Gerardo put his fingers through is gone.

The U.S. side of the park is now the strip between the fences, a kind of barren no man’s land. The white obelisk border monument is barely visible — it’s in Mexico now, behind a primary fence the Department of Homeland Security built in 2011.

Women walk past border monument obelisk #258 at the U.S.-Mexico border fence at Playas de Tijuana in Tijuana, Mexico.

The Mexican side is colorful and accessible. It is behind an old bullfighting ring and a lighthouse, with beach cafés and shopping.

Street sellers peddle paletas and raspados, and street musicians play accordion and guitar.

Just above the obelisk is a painting that shows two touching pinky fingers — a symbol of the newly reconfigured Friendship Circle.

Other murals and paintings on the Mexican side have messages in English and Spanish. “What God has joined together, let not man separate,” one says.

A decade ago, Mexicans and Americans could hold hands through the fence. But increased security, the new fencing, and an added layer of checkerboard style mesh metal fencing between steel bars means that now they may touch only pinky fingers — and only during visits supervised by the Border Patrol.

On weekends, agents let people into the U.S. side of Friendship Park for up to four hours so relatives can visit. Only 25 people at a time are permitted.

On the visiting day we attend it has rained, making the hike from the entrance more difficult. At one point we walk through water up to our knees, as do the families that come behind us.

Carmen Nepomuceno has tears of joy and she looks through the U.S.-Mexico border fence and can see her family on the other side at Friendship Park near San Diego.

Veronica Nepomuceno, a 43-year-old resident of Lakeside, California, arrives with five relatives including her sister, niece and 4-year-old great niece. They carry a stroller, folding chairs and a picnic lunch through the mud. On the other side of the fence, Nepomuceno’s mother, 63-year-old Susana Colin, weeps with happiness. The two have not hugged in 17 years.

Colin has flown to Tijuana from Toluca for the visit. Mother and daughter, both shrieking with joy, eat together but cannot share food. Only a tiny candy Skittle fits through the little squares of mesh fence, a boy tells me — but he warns that Border Patrol agents get mad if you try it.

Further down from the Nepomuceno clan, two sisters press against the fence, leaning in as they speak to their mother on the other side. The sisters, now 30 and 31 years old, tell me they came into the U.S. via Arizona when they were 14 and 15 years old. Their whole family made the grueling three-day walk. But years later, after their father died, their mother returned to Mexico. Their only visits are through the fence.

A group called Friends of Friendship Park is making efforts to hold binational events and beautify the U.S. side with a garden. They cite the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which promotes “relations of peace and friendship” so both sides, “should live, as good neighbors.”

The group is planning a campaign to allow hugging. Members hope to launch it Aug. 20, which will mark 45 years since Pat Nixon visited and was quoted as saying, “I hate to see a fence anywhere.”

Ultimately, members want unrestricted public access to the park.

“It’s baby steps,” volunteer Dan Watman says. “We’re going to start with hugs.”

FRIENDSHIP PARK

What: Friendship Park/El Parque de la Amistad

Also called: Friendship Circle.

Significance: With half of a circle in the U.S. and half in Mexico, it symbolizes international friendship between Mexico and the U.S.

Location: On the U.S. side it’s accessed via Border Field State Park in Imperial Beach, California, on the westernmost tip of the international border with Mexico. On the Mexican side it’s in a beachside area called Playas de Tijuana beneath a famous lighthouse,”El Faro.”

How it’s changed: The U.S. side is now in a restricted area between two border fences. The public no longer can walk on the U.S. side except during weekend visiting hours supervised by the U.S. Border Patrol.

Volunteer efforts: A group called Friends of Friendship Park formed after public access to the U.S. side of the circle was limited in 2009. Various groups hold binational events like yoga classes, salsa dancing and poetry readings through the fence, and binational gardens have been planted on each side of the fence. An annual Fandango Fronterizo musical event began nine years ago, and on Sundays there’s a regular binational border church.

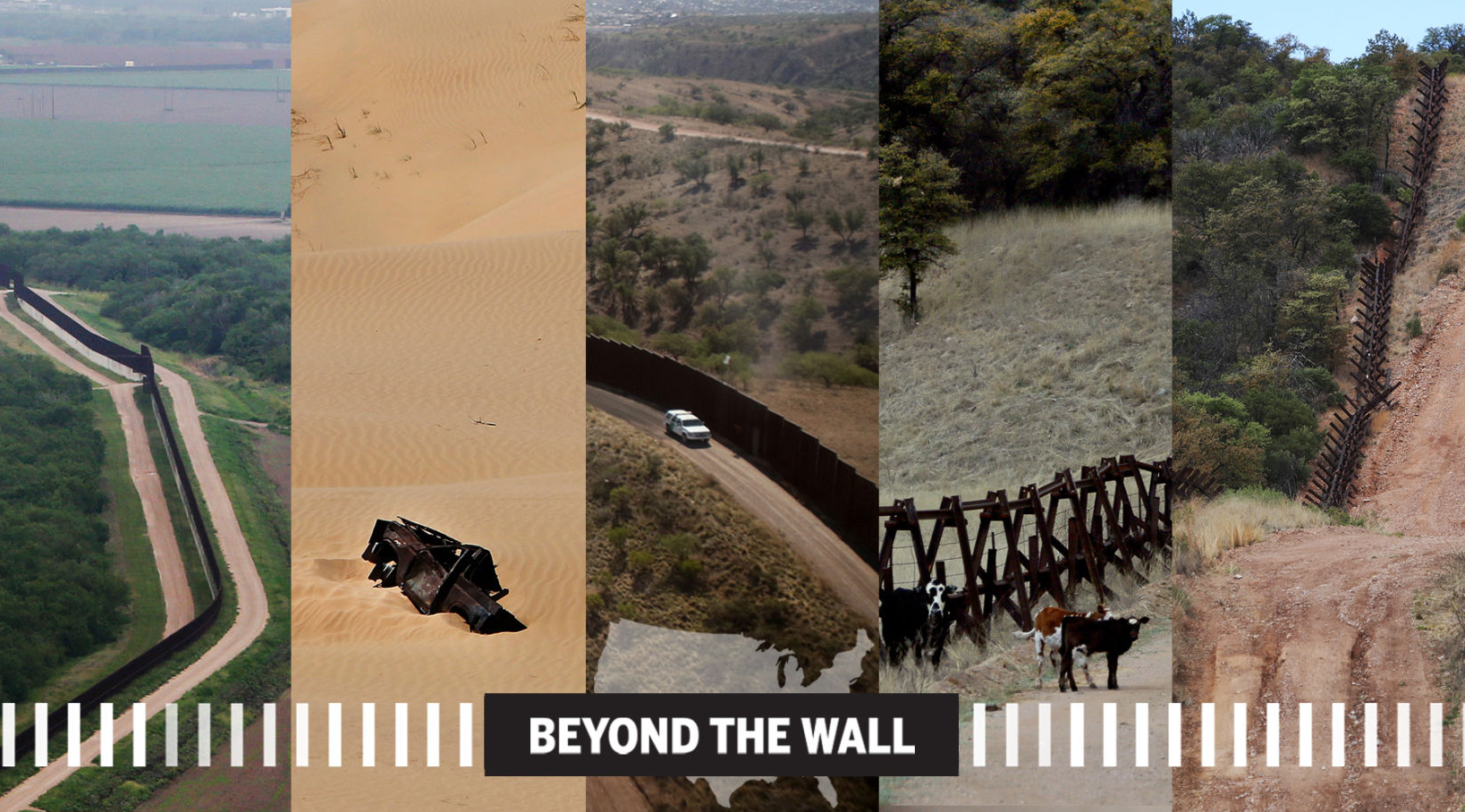

Beyond The Wall

Costly answer in California altering the landscape

Smuggler's Gulch, considered unfenceable a year ago, was indeed fenced. But environmental concerns linger about the $58 million project.EXPLORE BY STATE

CALIFORNIA

CALIFORNIA ARIZONA

ARIZONA NEW MEXICO

NEW MEXICO TEXAS

TEXAS