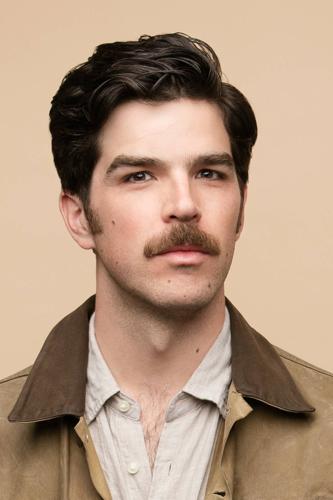

Protesters shouted down Tucson author Francisco Cantú in Austin, Texas, and called him a vendido, a sell-out.

Demonstrators disrupted his appearance in San Francisco, gathering in a bookstore to read aloud accounts of misbehavior by Border Patrol agents.

In Oakland, a bookstore canceled Cantú’s appearance altogether.

The offense this first-time author committed: He worked as a Border Patrol agent for 3½ years and wrote about those experiences in a book that is about the U.S.-Mexico border and the way our system of immigration enforcement grinds people up.

In other words, they were protesting an author who largely agrees with them.

It’s a strange new experience for Cantú, a 32-year-old almost seven years out of the patrol who fits in comfortably among the activists and academics in Tucson’s streetcar corridor. Demonstrators said voices of migrants need to be heard more than that of a former Border Patrol agent making money by recounting his growing ambivalence about the system he had joined.

“I agreed with everything they said,” he told me Friday about the San Francisco protest. “This was like a demonstration I would go to.”

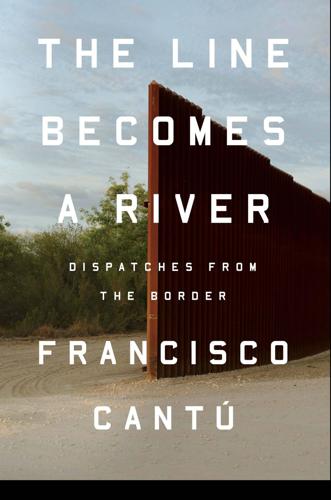

Except, of course, it was against him and his book, “The Line Becomes a River: Dispatches from the Border.”

The efforts to silence him I find inexcusable and all too typical of some activists in recent years. But I understand the criticism of what one Twitter critic called Cantú’s “reluctant migra schtick.” Cantú wrote this book during the second term of Barack Obama, a president known as cerebral and nuanced, sometimes to a fault.

Cantú’s writing is cerebral, nuanced and sensitive, too. And now, that can be viewed as a fault.

The book came out last month in a country divided by Donald Trump’s heavy-handed immigration policy. It’s a different country than the one in which Cantú wrote his book and sent to the publisher.

“I always imagined the book would be published in a time when it would be a relic of an uglier time,” he said.

While pro-immigrant activists have voiced their anger at Cantú, not much has been heard from more natural critics in Border Patrol circles. After a protest of one event, Cantú wrote on Twitter: “To be clear: during my years as a BP agent, I was complicit in perpetuating institutional violence and flawed, deadly policy. My book is about acknowledging that, it’s about thinking through the ways we normalize violence and dehumanize migrants as individuals and as a society.”

San Diego-area Border Patrol agent Shawn Moran, a former spokesman for the agents’ union, responded, “In over twenty years of BP service I have yet to see these deadly policies or institutional violence. I have heard several of your interviews and read excerpts, I congratulate you on maximizing media coverage through exaggerations.”

In the book, Cantú portrays his fellow agents in sympathetic terms, but in one passage acknowledges agents dumped migrants’ water and food stashes and urinated on their belongings. As the book progresses, he has a harder time doing the work, troubled by nightmares related to violence and death. Or maybe, better put, he does not want to change the way he must if he’s to continue in the job — to grow thick skin and slough off some of the sympathy he feels.

Among his fellow agents in Southern Arizona and the El Paso area, Cantú told me Friday, “I saw incredibly humane, compassionate people. I also saw a lot of assholes and people who got off on having a badge and a gun.”

In the book, Cantú mixes into the stories of his experience as an agent passages drawn from his reading about the border, about violence and other topics, quoting writers like the late Charles Bowden. Little of this will interest anyone who lives close to the border, spends time in the borderlands or has read much about the topic.

For me, it served as a reminder that he was a graduate student while writing, with his nose deep in books and historical documents. But it is precisely his stories of serving as an agent, and a gripping migrant story in the last third of the book, that make it worthwhile.

That latter tale evidently takes place in Tucson, though Cantú obscures identifying details throughout the book and involves the struggles of an undocumented family man he has come to know. This story, taking place in Tucson courtrooms and Eloy prisons, is a crucial endpoint, giving him a different view of the system he’d taken part in as an agent — and also giving voice to the story of an undocumented resident.

It’s ironic that the protesters objected to Cantú having spent time in the Border Patrol and profiting from the misery of undocumented people, like the family that is featured in the last third of the book. Those are exactly the parts that separate the book from the increasingly tired genre that could be called “My profound reflections on the border.”

Also, as Cantú noted, he’d be making a lot more money than he is now, as a writer working part-time jobs around Tucson, if he’d just stayed in the Border Patrol.

But there’s a frustration in reading his book. Cantú, who grew up in the Prescott area, graduated from American University after studying border issues there and joined the Border Patrol in search of answers. But when he left the patrol after winning a Fulbright scholarship to do research in the Netherlands, he didn’t have the answers, only more questions. He abandoned plans to become a policy-maker or maybe an immigration lawyer.

“Not going into policy-making, not going into immigration law was an act of surrender,” he told me. “I’m not ever going to become a person who comes up with a solution.”

That might be more acceptable amid the gradualism of an Obama or Hillary Clinton presidency, but it’s a let-down in a time of urgent need for action.