The instructions said jurors could ask questions, but still Dan Cormode was nervous when he started formulating one.

It was toward the end of the first day of what was to be a five-week murder trial that began Jan. 9 in Pima County Superior Court. Cormode started writing on the small yellow pad jurors were provided.

“The first time I asked a question, my hands were literally shaking,” he told me. “I was like, ‘I think this is going to be the stupidest question.’ I wanted to ask a question so that I knew how it was going to happen if I had a really important question I wanted to ask.”

He went ahead and submitted the question to Phoenix police Detective Karen Hughes: “Approximately how many homes would you enter without the resident present as a patrol officer?”

Judge Kenneth Lee summoned the attorneys, prosecutor Nicol Green and defense attorney Leo Masursky, who consented to the judge asking Hughes the question. That opened the floodgates. Over the five-week trial, jurors asked 99 questions, many of them multipart inquiries, including as many as eight separate questions in one.

Nobody knows if it was a record — probably not, considering that the rate of questions was about 20 per four-day week. But it was a lot, a flood, and showed how jurors in Arizona’s system can assert a bit of control over what can be long, difficult proceedings.

I learned of this case because Cormode, 43, is my neighbor, and his wife told me in January that he was picked to be on the jury for a long trial. The morning the trial started, I had my daughter at home, and we were looking for something stimulating to do, so I checked the court calendar and found the one five-week trial starting that day, the State of Arizona vs. Brian Ferry.

Claudia and I went downtown and watched the prosecution’s opening statement. I knew right away it would be a hard case for Green to prove beyond a reasonable doubt, especially with the stupendously logical Cormode, a Ph.D. in physics, on the jury.

A Phoenix couple, Charles Russell and Catherine Nelson, came to Tucson in February 2002, intent on buying a motorcycle they’d seen advertised in The Arizona Republic. They were never seen or heard from again. The main evidence that they arrived in Tucson was that their truck was abandoned in the parking lot at Santa Cruz Catholic Church, at West 22nd Street and South Sixth Avenue.

There was no clear evidence the defendant, Ferry, had placed the ad. It apparently was placed by someone using fictitious names.

The only physical evidence of a link between Ferry and the victims was that DNA matching Ferry’s was discovered in their truck. Ferry was arrested in 2015 after a break in the case: His father, John Ferry, distraught over a fight with his girlfriend, went to the Pima County Sheriff’s Department and told them his son had admitted killing them. The evidence was suggestive but circumstantial.

As detectives interviewed John Ferry, who had expected to be taken into custody for domestic violence, he grew impatient and uttered a classic line: “What does a guy have to do to be arrested around here?”

Watching that witness testimony, of a father against his son, was a particularly difficult experience in what was already a draining experience for juror Pete Shortell.

“That was the hardest thing for me to hear, his testimony,” said Shortell, 65. “The anguish that was in there, almost condemning his son.”

Once Cormode asked the first question, that broke the ice for fellow jurors like Shortell. While Cormode asked the bulk of the questions, at least 42, by my count, of the questions in the case file — identifying them by recognizable handwriting — Shortell probably asked the second most.

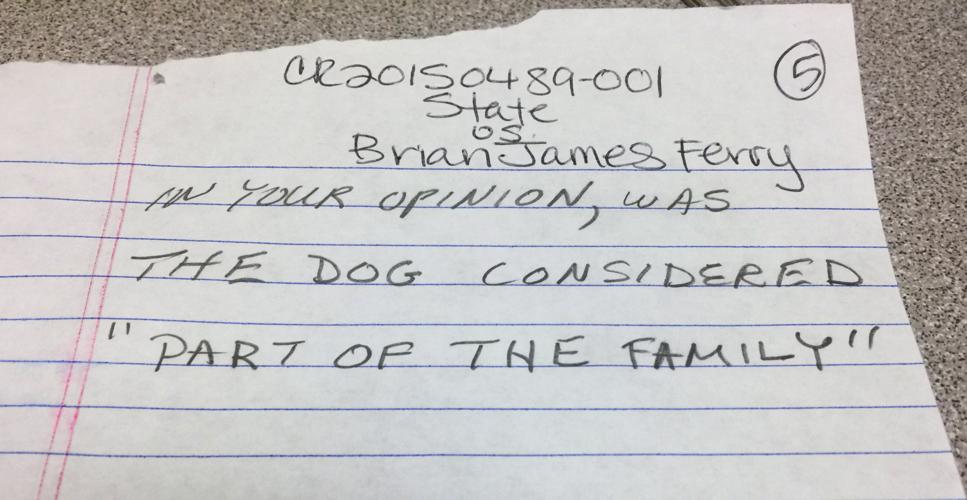

One of the questions asked struck me as absurd when I first read it: “In your opinion, was the dog considered ‘part of the family?’” That’s a question that Shortell had the judge ask the victim’s brother, Curtis Russell. The couple had left their dog in Phoenix when they came to Tucson to buy the motorcycle.

It turned out, Cormode told me, that was one of the most important questions asked. The answer, yes, confirmed for the jury their belief that Russell and Nelson were actually dead, and that they had not simply fled and left their lives behind.

“The questions that I asked, I felt I asked them because the prosecution didn’t ask them,” Shortell said.

The juror questions can be helpful for both sides, prosecutor Green told me, while avoiding commenting specifically on the Ferry case.

“Quite frankly, sometimes we forget to ask a question,” she said. “It helps both sides to focus our questions on the parts of evidence or testimony that the jurors seem to be focusing on as well.”

Arizona is one of just three states where judges must allow jurors to ask questions of witnesses. They’re given the opportunity after prosecutors and defense attorneys are finished with a witness, and any questions that jurors ask must be permissible under the same rules guiding the attorneys, those that forbid hearsay, irrelevant inquiries and the like.

In the highly publicized 2013 trial of accused murderer Jodi Arias in Phoenix, the defendant testified, and the jury took advantage of the opportunity by asking her more than 150 questions.

As the Ferry trial went on, more and more jurors joined in the questioning. By the 54th question, the court staff had stopped handwriting the case number on the questions and started using a stamp.

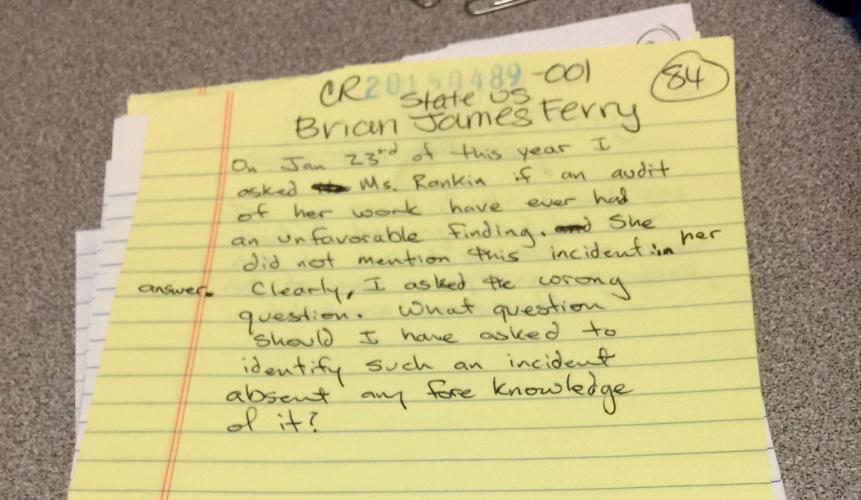

Cormode’s questions had become increasingly detailed. No. 51 was an eight-part question for witness Carol Birkhead, Brian Ferry’s former girlfriend. No. 95 was a six-parter. The questions even became self-referential:

“On Jan. 23rd of this year I asked Ms. Rankin (Nora Rankin, a retired Tucson police DNA analyst) if an audit of her work has ever had an unfavorable finding. She did not mention this incident in her answer. Clearly, I asked the wrong question. What question should I have asked to identify such an incident absent any foreknowledge?”

Cormode told me last week, “Sometimes I feared my questions were bordering on armchair detective.”

Shortell knew from his fellow juror’s skeptical questions that Cormode was leaning toward a not-guilty verdict. Shortell was leaning the other way.

In the end, the jury voted 9-3 for conviction but could not come to a unanimous verdict. A retrial is set for April 10. It was a frustrating conclusion to a case in which jurors kept involved by asking questions.

“A lot of us were very very engaged with everything that was being said. It was a mental strain,” Shortell said.

At the end of a day, he added, “It was like, ‘Aye aye aye’ — like you worked all day.”

That’s as it should be if you take your job as a juror, and part-time inquisitor, seriously.