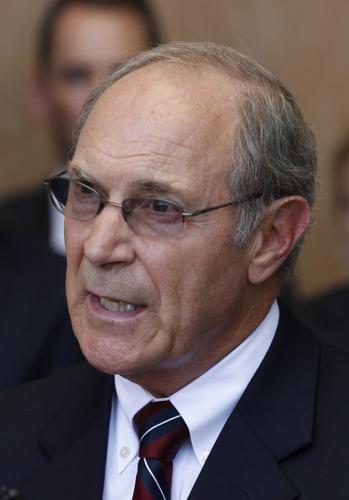

No one would have blamed John Leonardo if he had eased into retirement last January.

Leonardo served 19 years as a Pima County Superior Court judge, then in 2012 took over as U.S. Attorney for Arizona, working as the state’s top federal prosecutor for almost five years. He left that job with the change of presidents last year.

Now, though, instead of spending his days on a golf course or cursing at a TV, Leonardo, 71, finds himself holed up in Albanian offices with a team of jurists from the European Union. Leonardo is the only American among eight international advisers in an unprecedented effort to help rid the country of corrupt prosecutors and judges.

It’s a big job with massive significance for Albania and, potentially, other Balkan countries that might imitate the effort. The EU is requiring Albania to vet its 800 judges and prosecutors and remove those who are corrupt or incompetent as a condition for the country’s admission to the union. The EU is paying 10 million Euros to fund the project.

“It’s the first time this particular method has been tried,” Leonardo said. “There’s no template.”

However, there is pressure: “There are very high expectations in the country that a lot of judges and prosecutors are going to lose their jobs.”

I spoke with him by email earlier this month and by FaceTime from Tirana, Albania’s capital, on Tuesday. Here’s a compilation of his remarks, edited for clarity.

Q: What is the legacy problem with Albania’s justice system that you’re trying to address?

A: They just have rampant corruption in this country across many fields: Police, judges, prosecutors. Notoriously the Balkans in general have had that issue. The countries that were behind the Iron Curtain in the 20th century all seem to be having this problem.

Q: How is the process supposed to work?

A: The Albanians amended their constitution last year to require that all judges and prosecutors in the country undergo a vetting process in order to keep their jobs. The new law created a vetting commission made up of 12 Albanian lawyers selected by the Albanian Parliament who will sit in panels of three to investigate and hear evidence as to each of these judges and prosecutors related to three areas: unexplained assets, association with known criminals and professional proficiency.

Q: What is your role as an international observer?

A: There are eight of us, all in one huge room. All of us have at least 15 years as judges or prosecutors in our countries. It’s a pretty experienced group — many have worked in other countries before. We are supposed to give advice to these vetting bodies on legal matters and investigative techniques, organizational structures and interpretations of the vetting law. Then we sit in with them when they’re discussing the investigations of particular judges or prosecutors.

Q: Where are the other international advisers from?

A: Two from the Netherlands, plus Italy, Belgium, Croatia, Sweden and Bulgaria.

Q: How do you deal with the language barrier, since you don’t speak Albanian?

A: We have a staff of interpreters. The official language of the process is Albanian and English. Amazingly to me, of the eight international observers, I’m the only one whose native language is English, and yet we’re doing the official business in English. So I get called upon to be the final arbiter of what’s correct in English and review official documents before they go out.

Q: How far along are you in the process?

A: The first hearings are likely to be in the latter part of February. They’re assuming this process will take four to five years. It’s hard to imagine what it’s going to be like when the hearings start, because it’s going to be more intense. The hearing rooms are very small. They fit like six or seven people. They’re talking about having video feeds.

Q: What sort of problems are you seeing so far?

A: In general what we are seeing in the investigation is judges receiving bribes to dismiss charges against people; being paid to take a side in civil cases; freeing defendants who are wanted for extradition; judges who have assets five or six times more than what they earn.

Judges, in this country, for the last 10 years or so have had to make financial declarations of what they own, what their assets are, but we find they claim to live somewhere much more modest when they actually live somewhere much more lavish.

Q: How are you being received?

A: It’s reassuring to see that Albanians as a whole just expect so much from America.

I sense that I automatically have more credibility with the vetters, the legal community, than the Western Europeans do.

Q: How has your support been?

A: The U.S. ambassador here has been a big proponent of this process. The Albanians have a lot of regard for us and trust in us. Ambassador (Donald) Lu told a luncheon of the judges that if they looked at their wrists and they had a wristwatch that costs more than the average car, they probably wouldn’t be around next year.