For a couple of years now, we’ve seen a new Gov. Doug Ducey taking form.

The one we elected in 2014 focused pretty narrowly on cutting taxes and regulations to improve Arizona’s economy, changes he labeled “reform.” The one who’s appeared at State of the State speeches the last two years focuses, at least rhetorically, on addressing the state’s social problems.

The question is always whether he’s willing to go far enough to actually solve them, or if he’s too hemmed in by his own ideology, and his Republican allies in the Legislature, to get the job done.

This is what occurred to me as I listened to Ducey speak about reducing recidivism among the state’s outgoing prisoners.

It’s an admirable goal, and he made a practical proposal to continue expanding the Second Chance program that began last year at three prisons in Pima and Maricopa counties.

Last year, 603 inmates completed the program. This year, the governor is proposing to expand it by 975, which is great as far as it goes. But it needs to be understood in this context: About 19,000 inmates were released in each of the last two fiscal years. They served an average of about two years each.

So the problem of reintegration is much bigger than the small, steady steps the governor is proposing. And while helping inmates get jobs and get back into society without re-offending is a big issue, it’s not the biggest one in our prison system.

The elephant in the room, the problem that people on the political left and right are desperate to address, is our Draconian sentencing regime.

A relic of the 1990s crackdown on crime, Arizona has stiff mandatory minimum sentences for felony crimes, leaving judges little discretion, and, crucially, the state still requires that each convicted felon serve a minimum of 85 percent of his or her term.

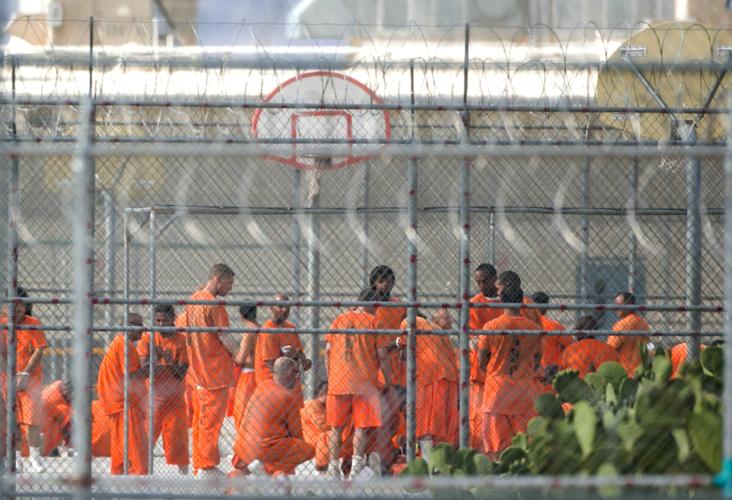

The result has been that Arizona’s prison population has soared far faster than the state’s population. It now has the fifth-highest incarceration rate in the country, according to the Sentencing Project. That group shows Arizona had 596 inmates per 100,000 residents in 2015, the last year for which Bureau of Criminal Justice data for all states were available.

Only such bastions of progressivism as Louisiana, Oklahoma, Alabama and Mississippi had higher rates.

I say that facetiously, of course. But Mississippi actually is more progressive than Arizona when it comes to sentencing. Under a law signed in March 2014, violent criminals must serve a minimum of 50 percent of their prison sentence, and nonviolent criminals must serve a minimum of 25 percent.

Our laws have been filling our prisons year after year, though finally now, as Ducey noted, “Arizona is experiencing the largest drop in the number of inmates in our prisons since 1974.”

That isn’t saying much. To explain what he was referring to, spokesman Patrick Ptak told me that from the end of fiscal year 2016 to the end of fiscal year 2017, the number of Arizona prisoners dropped by 702, from 42,902 to 42,200, a 1.6 percent drop.

But a look at the precise change that has occurred during Ducey’s time in office is not as flattering. On Jan. 5, 2015, when Ducey took the oath of office, Arizona had 42,004 state prisoners. On Tuesday, Arizona had 41,699 prisoners, a decrease of 7/10th of 1 percent.

While they are fans of Ducey and his attempts to address prisoner re-integration, even conservative advocates of sentencing reform recognize he could aim higher.

“Ultimately what I want to see is a society that is safe with as few people in prison as possible and at the lowest cost possible,” said Andrew Clark, state director of Americans for Prosperity.

“Almost 25 percent of the state’s prison population is there for nonviolent offenses,” he said. “Is that a good use of a quarter of a billion dollars?”

Clark was referring to the more than $1 billion the state spends on the Department of Corrections. Freeing up $100 million here or there could, of course, help solve some of Arizona’s other problems, like teacher pay.

Alessandra Soler, state director of the ACLU, said of Ducey, “His focus on giving people second chances is a huge step in the right direction, but we really need to look at the reasons people are in prison in the first place and how long we’re keeping them there.”

Other conservative states have taken a more open-minded approach to prison sentencing than Arizona has, she noted.

“They made it easier in Louisiana to earn good time,” she said. “If you know you can earn release time, you’re more likely to participate in educational programs and work. All of these will be essential to your success.”

Ducey told the Yellow Sheet Report on Monday that he’s sticking with the more modest efforts right now. “If we want to talk about different reforms around our sentencing guidelines, that’s a totally different subject,” he said. He added that a discussion about sentencing reform would be “worthwhile” and he’s “open-minded” on it.

Clark, Soler and Kurt Altman of the conservative group Right on Crime all noted that Ducey is focused on “back end” solutions — those that deal with prisoners being released.

Those are good in that they deal with a problem right in front of us. But they don’t confront Arizona’s central prison problem, which is an archaic sentencing structure that puts too many people behind bars, for too long, at too great a cost.

If Ducey wants to grapple with social problems like criminal justice, that is an ambition worth pursuing and a real “reform” worth achieving.