Ecologist Ray Turner documented the invasion of mesquites into desert grasslands over a century.

Turner also helped document the decline of the Santa Cruz River south of Tucson over the same period.

He also documented the impacts of climate change on the Sonoran Desert long before that kind of research was fashionable.

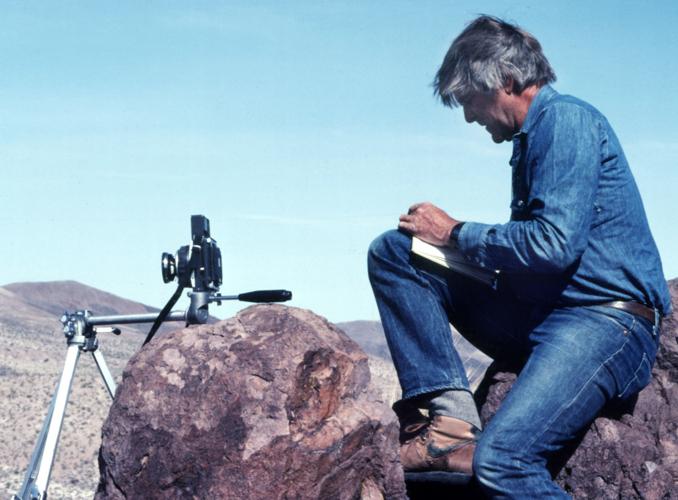

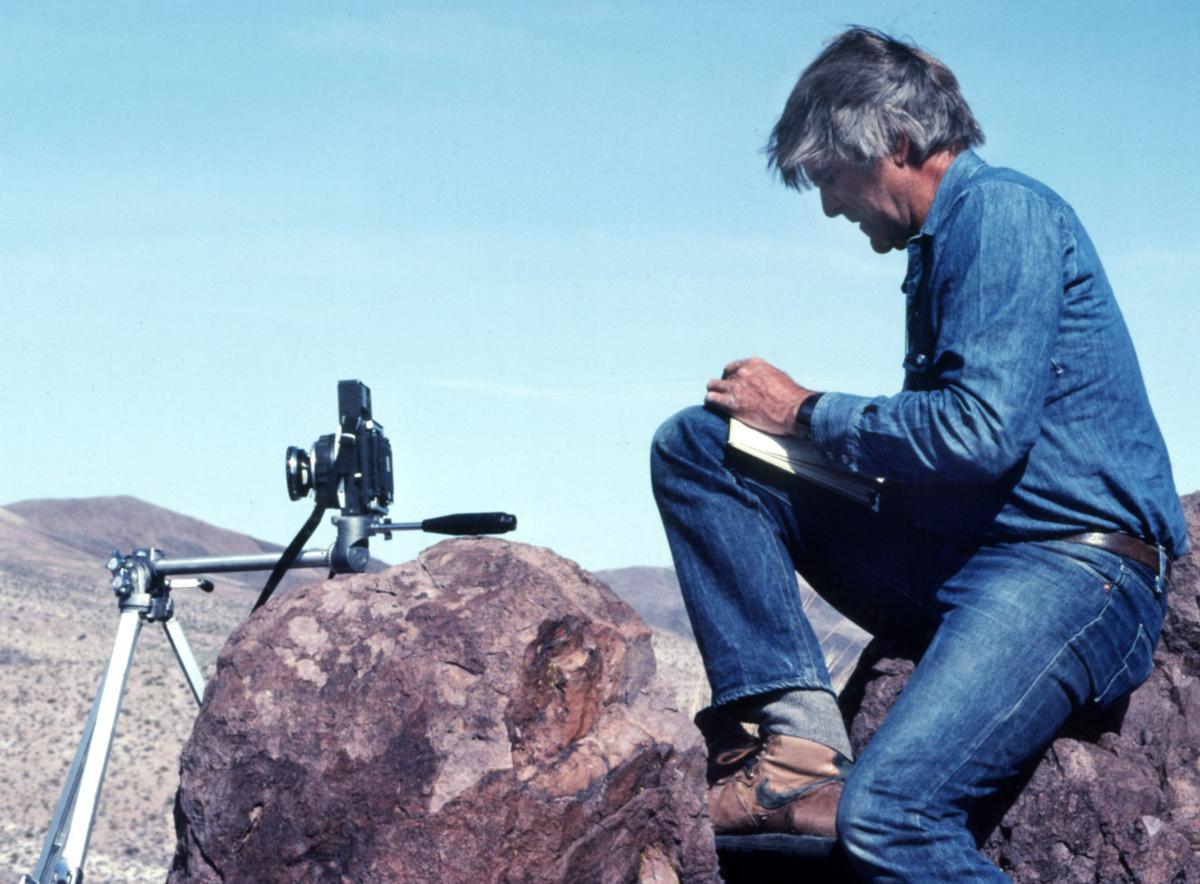

And after Turner’s death this month following more than 60 years of groundbreaking desert research, some of his colleagues say his kind won’t be seen again. His brand of basic research involved camping and backpacking across the desert, from Southern Arizona to Kenya, to gather plant data, a far cry from contemporary researchers who look to satellite transmissions and computer models.

Turner died Dec. 9 at age 91, after suffering a stroke at a Tucson assisted living facility.

Ray Turner

His death came roughly four years after publication of the last major book he co-authored, “Requiem for the Santa Cruz.” It chronicled the death of the Santa Cruz at the hands of Tucson’s burgeoning population.

That came almost a half-century after his first major work, “The Changing Mile,” showed how climate, livestock grazing, fire suppression and other forces had transformed the Sonoran Desert since the 1890s.

In between came at least three other major books and numerous research papers that he authored or co-authored or made possible for others to write through his encouragement and support.

Turner was one of the first researchers to detect bigger shifts and larger dynamics of ecological change across the region, said Ben Wilder, director of the Desert Laboratory at Tumamoc Hill, where Turner worked for well over half a century.

He was a U.S. Geological Survey researcher there from 1962 until officially retiring in 1989. He carried on there afterward, basically performing the same work, until finally slowing down earlier this decade.

Turner popularized the use of repeat photography to uncover and illustrate vegetation shifts. Typically, he employed photos from the late 19th century, the middle-to-late 20th century and beyond.

“His legacy is both time and space,” said Julio Betancourt, a former Desert Laboratory co-director and now a scientist emeritus for the U.S.G.S. in Reston, Va. “A lot of people do work at a particular place. He did it over decades. He did it everywhere.”

Turner’s daughter, Teresa Hadley, recalled the meticulousness her father employed when he and his family traversed remote Southwestern U.S. and Mexican deserts to research their plant life.

“I witnessed the precision, care, truthfulness, and concentration, even goodwill that it required and also the reverence. It meant that we had to become as immersed in the natural world as he was, to be a part of his ecology, the interconnectedness of all life,” Hadley recalled.

Among Turner’s key discoveries:

- In “The Changing Mile” and “The Changing Mile Revisited,” published in 2003, Turner and several colleagues used repeat photos from 300 sites to show how cattle grazing triggered the invasion of mesquites into grasslands, improving habitat for some imperiled species such as the Southwestern willow flycatcher, and hurting it for others, such as the Baird’s sparrow and the pronghorn.

By gobbling up grass, cattle removed fuels that had sparked wildfires on this landscape, allowing trees to grow. The cattle also spread mesquite seedlings with their feces, said Robert Webb, himself a retired U.S.G.S. researcher who worked with Turner for 35 years including on the 2003 “Changing Mile” volume.

The book also documented impacts on vegetation of a hotter, drier climate, of periods of unusually heavy flooding, and of federal fire suppression.

- In 1980, Turner and researcher Martin Karpiscak of the University of Arizona published a study documenting how closing of the gates at Glen Canyon Dam in 1963 dramatically changed vegetation along the Grand Canyon downstream. By reducing flooding, the dam allowed the growth of native cottonwoods, willows and cattail — and non-native species such as tamarisk, Russian olive and camelthorn.

- Starting at Tumamoc in the 1960s, Turner led a systematic effort to monitor saguaro populations, now covering 11 locations, including Saguaro National Park-West and East. While many of the saguaro populations have grown and/or declined over the years, the researchers still haven’t detected a discernible, regional population trend over that time.

- In the 2007 book “The Ribbon of Green,” Turner, Webb and a third author showed that while many experts have long said that Southwestern riparian areas have declined by up to 90 percent, repeat photos show that the amount of this vegetation had actually increased significantly across the region.

Ray Turner, at age 80, at Sierra Cucapa near Mexicali, Mexico in 2010.

- But the 2014 Santa Cruz River book showed that didn’t mean there’s no reason to be concerned about riparian areas, said Webb, a co-author on that one, too. Besides showing how floods led to natural arroyo cutting that lowered water tables, it tracked Tucson’s groundwater pumping due to population growth, the drying of the river and the decline of neighboring bird populations.

The book focused heavily on the death of a huge mesquite forest along the river, lying about 2 miles south of Tucson.

Covering at least 7 square miles, it occupied the Tohono O’odham Nation’s San Xavier District, was known as the Southwest’s most famous mesquite bosque and played host to 73 nesting bird species, the book said. It drew ornithologists from all over the U.S. But by the early 1980s, due to groundwater pumping, woodcutting and road construction, “nothing remained (of the forest) but dead stumps,” the book said.

“This book was to show that, oh yeah, we’ve had some big disasters, and we know it,” Webb recalled.

These last two books illustrate a key element of Turner’s research. While he was by nature a strong conservationist, his research was directed at uncovering facts, not pursuing a political agenda, his colleagues Webb, Betancourt and Wilder said.

“Ray was a classic, classic objective scientist,” Webb said. “He followed what the data told him, not preconceived ideas. That was one of his biggest strengths.”

Likewise, Turner’s “Changing Mile” books ended not with policy prescriptions, but with calls for continued research.

As more is learned about our region’s past climate and its flora and fauna, “better answers to questions of causation will inevitably emerge, and these answers will be based less on speculation and more on fact,” both versions said. “For now, the changing mile must remain a good subject for debate, but an even better subject for study.”