Hundreds of millions of dollars in federal funds to conserve water in the Colorado River Basin — including $86.6 million for advanced wastewater treatment in Tucson — have been frozen by the Trump administration, Arizona’s senators say.

U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly’s office said funding for all projects related to the river that were to be financed by the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act — which include the Tucson project — are frozen. Specifically, the Tucson project to treat wastewater to drinking-water standards is on a federal website’s list of frozen projects, said David Wegner, a retired U.S. Bureau of Reclamation official.

Another of the highest-profile river water conservation awards, $107 million that the federal government agreed in October to provide the Gila River Indian Community in Central Arizona, is also held up, said a tribal attorney.

“As far as we can tell, all funds are frozen through the IRA,” tribal attorney Jason Hauter confirmed. The Inflation Reduction Act was one of the prime sources of water conservation funding for river water users.

Before they were stopped, the funds were all aimed at directly conserving Colorado River water use by farms and cities in Arizona or building projects such as the wastewater purification plant in Tucson to provide alternative drinking water sources to the river’s water supplies, which are dwindling due to long-term drought and climate change.

Tucson City Manager Tim Thomure said Friday Tucson has received no official notification, “one way or the other,” on funding for its Advanced Water Purification project since President Donald Trump issued an executive order on Jan. 20 putting on hold spending under the Inflation Reduction Act.

“It is our understanding that the funding is at risk based on the recent actions of the new administration,” Thomure said in an email to the Star. “We are hopeful that the new administration will provide clarity on what projects will proceed soon.”

“This is a core infrastructure project that directly contributes to the long-term reliability of the Colorado River,” he said.

Treated wastewater from the Tres Rios Wastewater Reclamation Facility, shown here, would be further treated to drinking water quality under the Tucson plan that would be funded by up to $86.7 million through the now-paused Inflation Reduction Act.

Arizona Democratic Sens. Kelly and Ruben Gallego announced Tuesday that they have learned river conservation funding is frozen.

They emphasized that stopping the money for what’s known as the Lower Basin Conservation and Efficiency Program could undo the collaboration needed to keep the river flowing, “and lead to projects and companies collapsing.”

Separately, a Kelly spokesman said, “The Trump administration’s decision to freeze funds that could endanger the Colorado River is reckless leadership that puts our communities at risk. Senator Kelly has spoken to cities, tribes, and other water users about how these irresponsible funding freezes may affect them. He also spoke to Department of Interior Secretary Doug Burgum about this.”

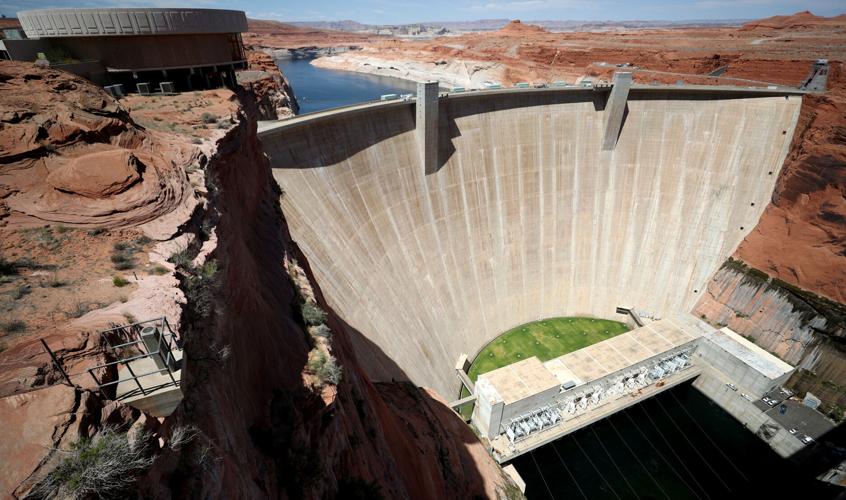

Another consequence of the freeze is that it has delayed repairs at 63-year-old Glen Canyon Dam, the senators said. The Bureau of Reclamation had set aside about $30 million for a wide range of projects, including replacing the dam’s power plant fire alarm system and various service transformers and switchgears. Also delayed is refurbishment of the dam’s power plant and cranes.

The funding freeze has delayed repairs at 63-year-old Glen Canyon Dam, Arizona's U.S. senators say. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation had set aside about $30 million for projects including replacing the dam's power plant fire alarm system and various service transformers and switchgears, and refurbishing the power plant and cranes.

Trump announced in an executive order on his Inauguration Day that he was “pausing” spending of funds appropriated by the Inflation Reduction Act and the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. The White House labeled the effort “Terminating the Green New Deal,” invoking a phrase used to describe large-scale investments in environmental programs. “Agencies shall prioritize cost-effectiveness, American workers and businesses, and the sensible use of taxpayer money,” the president wrote.

The next day, Jan. 21, the White House budget office released a memo saying the freeze applied mainly to energy-related projects and policies, particularly anything discouraging the use of fossil fuels. Neither the order nor the follow-up memo made any mention of water conservation projects or the Colorado River.

An Interior Department spokeswoman released a statement Friday saying, “The Department of the Interior continues to review funding decisions to be consistent with the President’s executive orders. The Department’s ongoing review of funding complies with all applicable laws, rules, regulations and orders.”

The statement didn’t say if funds are being frozen or otherwise held back. Asked about that by the Star, the spokeswoman replied, “The department doesn’t have any further comment.”

Hauter said that as far as he knows, all recent awards to Arizona water entities for conservation purposes have been frozen. Tribal officials have written two letters to Burgum asking that the freeze be lifted, Hauter said.

“The Colorado River is in the midst of a historic drought, and our constituents are working on solutions to keep the river flowing,” the U.S. senators’ news release said Tuesday. “This winter snowpack accumulation is below average, so we need to do everything we can to improve conservation. This means making sure projects receive support and funding.”

By far the biggest source of funds on hold is the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. It was mainly passed to infuse the country with big investments in renewable energy, and tax credits for “green energy” products such as heat pumps and electric vehicles. Arizona senators, working with those from other Western states, managed to get $4 billion of the act’s funds set aside for drought relief programs.

Another chunk of funding comes from the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, passed to funnel billions of federal dollars into roads, bridges and transit systems as well as water projects.

Tucson’s wastewater purification plant would be built on the metro area’s northwest side, an area whose residents have had a number of their drinking wells closed due to contamination by PFAS chemicals.

But that plant — which would be the city’s first venture into treating wastewater to drinkable quality — was included on a list that Wegner, now a National Academy of Sciences board member, got of affected projects.

Other projects on that list include the Gila River community’s funds, $154 million to the Phoenix-based Salt River Project utility to connect its canal system to that of the Central Arizona Project, $13 million for upgrading pipelines at Gilbert’s Riparian Preserve, and $25 million to upgrade wetlands in the Yuma Area and at Topock Marsh in the Colorado River’s Havasu National Wildlife Refuge. Upgrading the riparian reserve would increase recharge, ultimately saving river water, while maintaining wetlands is important to the river’s health, project officials say.

“We’ve been appealing to Interior how this doesn’t fall under any of your directives. It’s not part of the Green New Deal or DEI,” Hauter said, referring to the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion programs the Trump administration has been killing off on a federal level.

“We’re hopeful it will be dislodged. As they go through all this, they’re kind of scrutinizing government funding. We think after looking at this, they’ll free it up,” Hauter told the Star.

The Salt River Project doesn’t anticipate Trump’s order will have an impact on the SRP-CAP interconnection facility, said utility spokeswoman Patty Garcia-Likens, not explaining why. A Gilbert spokeswoman, Jennifer Harrison, declined to say if the city’s federal funds are being held up, saying, “We are awaiting further clarification from the federal government.”

The Imperial Irrigation District in Southern California, owner of the most water rights on the Colorado River, didn’t respond to a question from the Star about whether its funds are held up. It was awarded over $500 million in September from Reclamation to compensate for agreeing to save 700,000 acre-feet total from 2024 through 2026.

One reason some agencies aren’t commenting is fear of retribution from the Trump administration, Wegner said. “Nobody wants to get on the wrong side of who’s monitoring what’s happening with the money,” he said. “People are scared.”

One of the Gilas’ plans for use of their $107 million is to line irrigation canals to prevent leakage. Another is to improve efficiency of water use on the reservation’s farms. The third is for a “regulating reservoir” to store water, if a grower decides “at the 11th hour” it’s not needed, so it doesn’t “spill” outside the tribe’s irrigation system into the desert, Hauter said. “It would capture excess water so you are not losing it,” he said.

The Gila River Indian Reservation, which has the largest single share of Colorado River water in Arizona, hopes to use federal funding to increase the efficiency of its farms' water use, tribal officials say.

The Gila Community has the single largest share of river water rights in Arizona, of up to 311,000 acre-feet annually delivered by the CAP canal system, although deliveries have been reduced in recent years due to river shortages.

As the Colorado River loses water, “We want to be as efficient as possible to adjust to the new normal, whatever it looks like,” Hauter said.

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis talks about the viability of seawater desalination and wastewater treatment as alternatives to reliance on the Colorado River.