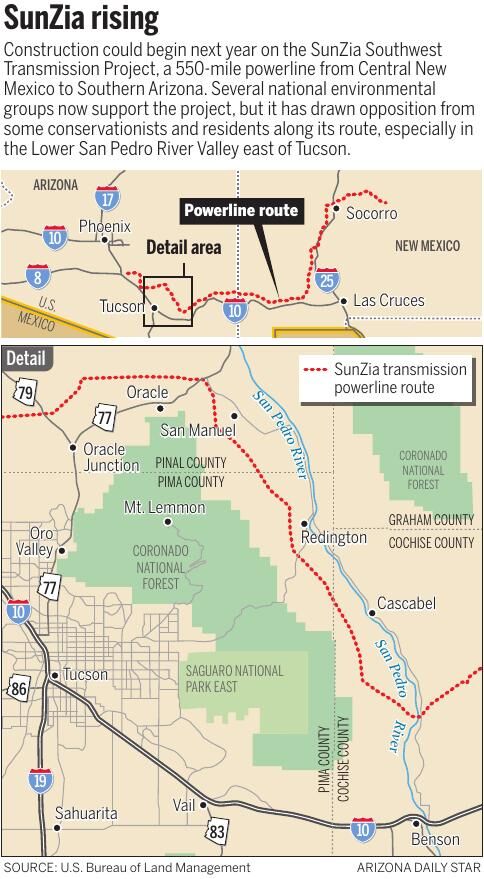

CASCABEL — After 16 years of reviews, changes and challenges, the first high-voltage towers could go up next year in the Lower San Pedro River Valley, as work finally begins on a 550-mile power line from central New Mexico to Southern Arizona.

The SunZia Southwest Transmission Project successfully wrapped up its permitting process with Arizona power regulators last month. A federal environmental review of the project is slated for completion in the spring, clearing the way for construction of the transmission line first floated in 2006.

Originally proposed for other purposes, the project is now designed to carry power from what would be the largest wind energy development in the Western Hemisphere, a 3,500-megawatt array of massive turbines set to be built starting next year across three New Mexico counties.

Developers are calling the wind farm and transmission line the largest renewable energy infrastructure project in U.S. history, with a combined investment of more than $8 billion and enough capacity to deliver power to more than 3 million people.

Opponents along the power line route on the eastern slope of the Rincon and Catalina mountains call it something else.

“It’s an ecological travesty,” said conservationist Peter Else, who lives along the San Pedro near Mammoth and has fought against the project throughout the permitting process. “This is really the only natural and intact river system left in Southern Arizona.”

The mostly undeveloped valley east of Tucson is widely recognized as a haven for biodiversity and an internationally important corridor for hundreds of bird species, both native and migratory.

Signs are posted in Cascabel against the SunZia Southwest Transmission Project.

The Lower San Pedro is home to federally designated critical habitat for the endangered Southwestern willow flycatcher and the threatened Western yellow-billed cuckoo. More than 190,000 acres there have been protected to offset the environmental impacts from development projects elsewhere in Arizona.

Though several national environmental groups have since lined up behind the transmission line and the green energy it will deliver, Else and other opponents still cling to the hope that they can stop construction or get the line moved somewhere else.

As Cascabel resident and conservationist Pearl Mast put it, “We feel that there’s definitely still a lot of fight to go on.”

A lot on the line

The proposed power line and the enormous wind farm that will feed it are now owned by Pattern Energy Group.

The San Francisco-based renewable energy giant also owns Western Spirit Wind, a 1,050-MW collection of turbines that began generating power in central New Mexico a year ago.

Pattern acquired the SunZia transmission project earlier this year. Company officials hope to get it built and activated by late 2025, when its SunZia Wind development is also slated to go online.

Pattern spokesman Matt Dallas said the power line route was selected nearly a decade before they bought it, but it still presents “the best path compared to the alternative routes that would have had significant impact on wildlife areas and disadvantaged communities.”

The Arizona portion of the line would stretch for about 200 miles and include approximately 780 towers ranging from 55 to 195 feet tall.

Each structure would carry two 500-kilovolt lines — one owned by Pattern to move energy from its latest wind development in New Mexico, the other separately owned and expected to carry solar and other renewable power generated in the region.

The SunZia Southwest Transmission lines will cross the scenic San Pedro River Valley as seen from the Cascabel Conservation Association.

SunZia would enter Arizona in southern Greenlee County and march west through rural areas north of Bowie and Willcox, where it is slated to pass within about a mile of the popular Apple Annie’s Produce & Pumpkin Patch before angling southwest toward the San Pedro.

The line would cross the river about 14 miles north of I-10 in Benson and then hook north, skirting the rugged, mostly empty west side of the valley on its way toward San Manuel, Oracle and its final destination: a connection to the grid at a yet-to-be-built substation near Coolidge.

Transmission line through the Lower San Pedro Valley inches closer to reality, despite opposition.

Change in tone

Even staunch opponents of SunZia have noticed a change in tone since Pattern acquired the project. Else and others say the new owner seems more interested in community engagement and more inclined to discuss environmental mitigation than the previous owner was.

Adam Cernea Clark is senior manager of environmental and natural resources for Pattern.

He said the company’s close work with conservation groups in Arizona and New Mexico could be “precedent-setting” for future projects of this kind.

“We’re really proud of what we’ve done. We’re just really excited and proud of this project,” Cernea Clark said.

Pattern is still finalizing the implementation of its overall mitigation agreement with the Arizona Game and Fish Department, but the company has already committed to a wide range of measures, from strict speed limits for construction vehicles on rural dirt roads to seasonal building schedules designed around the nesting and migration patterns of birds.

In Paige Canyon and other remote places along the Lower San Pedro, the transmission towers will be placed using helicopters instead of heavy equipment on the ground.

Two of Pattern’s biggest mitigation investments come in two of the most sensitive areas along the route. In the San Pedro Valley, the company is in the process of purchasing 140 acres of private property at the mouth of Edgar Canyon near Redington to be donated to Pima County as conservation land. And in central New Mexico, Pattern plans to buy and conserve a 1,225-acre farm between Interstate 25 and the Rio Grande River north of Socorro as a possible addition to the nearby Sevilleta National Wildlife Refuge.

The company has also committed to what Cernea Clark called “voluntary compensatory mitigations” that extend beyond the project area. They include investments in conservation research, the development of water catchments for wildlife, and the removal of invasive buffelgrass, which poses a threat to the broader Sonoran Desert ecosystem.

Advocates divided

Major environmental groups such as Western Resource Advocates and Defenders of Wildlife are publicly supporting SunZia as a way to fight climate change.

But specifics of the project have divided other conservationists, including some within the same organization.

The National Audubon Society and Audubon Southwest, its regional arm in Arizona and New Mexico, have come out in favor of SunZia. The Tucson Audubon Society still opposes it.

Pearl Mast and David Omick live in a 128-square-foot home and are completely off the grid near Cascabel. They have solar power for electricity and use captured rainwater for cooking, bathing and everything else.

David Robinson, director of conservation advocacy for the local group, said the Lower San Pedro is simply too fragile and too important to be opened up for industrial development.

“The river itself is already very endangered, and the threats keep coming,” he said. “If it were up to us, (SunZia) wouldn’t be built there.”

But Jonathan Hayes, executive director for Southwest Audubon, said he thinks the project can be a “net-win” for bird species and the environment as a whole — and not just by reducing greenhouse-gas emissions and helping to stave off mass extinction.

Though there is no such thing as a transmission line that is perfectly safe for birds, Hayes said such losses can be reduced with collision countermeasures and more than offset with habitat improvements elsewhere.

He said Pattern has shown a commitment to reducing avian deaths by marking lines with reflectors or UV lights to make them easier for birds to see them in high-risk areas.

The company has also agreed to make landscape improvements along the route by reclaiming unnecessary roads and avoiding, relocating or replacing saguaros, agaves and other important native plants at a “more than 1-to-1 ratio,” Hayes said.

For a long time, he said, the environmental community has dedicated itself to stopping any and all industrial development, but the existential threat posed by global warming has changed that equation. Over the next 10 to 20 years, environmentalists will need to find a way to “get to yes” on projects like SunZia and other efforts to expand renewable energy, he said. “We have to enter into these things in good faith. We can’t keep moving the field goals around.”

Robinson said the Tucson group is taking a pragmatic approach to the project these days. Though they object to SunZia’s route, they recognize “it’s very unlikely it will be stopped.”

For them to drop their opposition, he said, the ongoing federal environmental review process must result in “real, robust mitigation measures” that SunZia is required to follow.

“If this project goes forward, our hope is it can be a model rather than a bitter pill to swallow,” Robinson said. “We won’t know that until we see it in writing in great detail.”

Pattern Energy plans to buy 140 acres near Redington and donate it to Pima County as mitigation for the new transmission line the company is getting ready to build through the Lower San Pedro River Valley.

Off the grid

Pearl Mast and David Omick don’t need any lectures about the virtues of renewable energy.

Since 1997, they’ve shared a 128-square-foot, solar-powered home they built themselves in a ravine surrounded by towering saguaros in Cascabel, about 80 miles from Tucson by road, the last 7 of it unpaved.

They live completely off the grid, using just a fraction of the power of the average American household, but they still enjoy a strong enough internet connection to post how-to videos on sustainable living.

Their house looks out over Mica Mountain, the Rincon Mountain Wilderness and the highest, easternmost reaches of Saguaro National Park.

Though a portion of the proposed power line would be visible from their porch, Mast and Omick insist they aren’t just a couple of NIMBYs. The San Pedro is far bigger and more important than their view.

“It’s one of the most biologically diverse areas in the country,” Omick said. “We have a lot of the neo-tropical species like coatis and javelina, and we also have a lot of the species that you’d find much further north in the U.S. It’s really exceptionally rich.”

And while government agencies and national nonprofits have come to recognize the Lower San Pedro as a relatively unspoiled place worthy of protection, it’s the locals who have long led the charge.

This valley of fewer than 200 residents is home to a host of environmental advocacy groups, including the Cascabel Conservation Association, the Cascabel Working Group, the Lower San Pedro Watershed Alliance and the Saguaro-Juniper Corporation.

In the early 2000s, some of those local landowners and advocates spent several years painstakingly stitching together a conservation easement across their properties to preserve one of the most important wildlife corridors between the Rincons and the Galiuro Mountains.

“These lines would run right down that corridor for a couple of miles,” Mast said.

There is also a great deal of concern over how SunZia gets built.

Conservationists worry that new access roads to allow for construction and maintenance of the line will further fragment wildlife habitat, foster the spread of invasive plants and invite illegal off-road vehicle use.

And once the new transmission corridor has been established, opponents fear it’s only a matter of time before more utility, industrial and infrastructure projects show up to fill it.

“Once you’ve got a line in there, anything else can be co-located there,” Omick said.

Fight goes on

In testimony before the Arizona Corporation Commission, Pattern officials said they are in talks with 60 to 70 potential customers for the massive wind farm they’re about to build in New Mexico, but no power purchase agreements have been announced.

Ultimately, Peter Else predicts Arizona utility customers will see very little benefit from SunZia. He said the bulk of the electricity will almost certainly be sold in California, where higher prices and strict green-energy mandates ensure the biggest return for the company.

That’s one of many arguments Else has made against the project since he officially intervened in the corporation commission’s review of it in 2015.

He has also challenged the power line several times in court — so far unsuccessfully — including a case decided in SunZia’s favor by the Arizona Supreme Court in 2018.

This time around, Else has hired a law firm in hopes of getting the commission and the courts to take his claims more seriously.

That process began on Monday, when Else and his attorneys filed a formal request for a rehearing before state power regulators.

If that doesn’t work, the fight over the power line is almost certain to end up in court once again.

“It’s been a very difficult struggle,” Else said. “I intend to pursue every option for as long as I have the resources to pursue them.”