MotoSonora Brewing Co. had no choice but to invest in expensive equipment and can its Victory or Death IPA and Fog Lights Hazy IPA when brothers Jeff and Jeremy DeConcini opened just weeks before the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

But what seemed like a great way to introduce their beer to Tucson consumers who couldn’t come to the brewery has become somewhat of an albatross after President Trump slapped a 25% tariffs on Canada’s steel and aluminum.

“At our scale, we are very sensitive to the price of aluminum,” said Jeremy DeConcini, who said he didn’t know yet how the tariff will impact his costs. But any increase “will mean we can’t sell as much far and wide,” he said.

Customers enjoy local brews at Moto Sonora Brewing Company, 1015 S. Park Avenue.

American manufacturers get 60% of their aluminum from Canada, which means higher prices for cans on top of the steadily increasing costs for malt, hops and grains needed to make beer.

Tucson craft breweries say Trump’s tariff could put a hurt on an industry already facing an uphill battle to stay viable in a shrinking marketplace. Beer sales, like sales of wine and spirits, has seen a dramatic decline in the past two years as consumers opt out of drinking alcohol.

“The bubble for craft brewing is over,” said Borderlands Brewing Company owner Es Teran, pointing to two recent Tucson brewery closures — Dillinger Brewing in late 2023 after seven years and Firetruck Brewing in late January after 14 years.

“There’s different reasons, but people extended themselves at the pandemic and at the same time, the consumers have changed,” he said. “People are drinking seltzers or mocktails.”

Legalized recreational marijuana also has cut into the market, he said, echoing an argument Southern Arizona winegrowers made last year as many saw a dramatic drop in sales.

“You can take an edible and drink a soda and you’re having a good time,” Teran said. “I think we have to adapt, and at the end of the day, you have to cut some costs. The cost right now is in the packaged.”

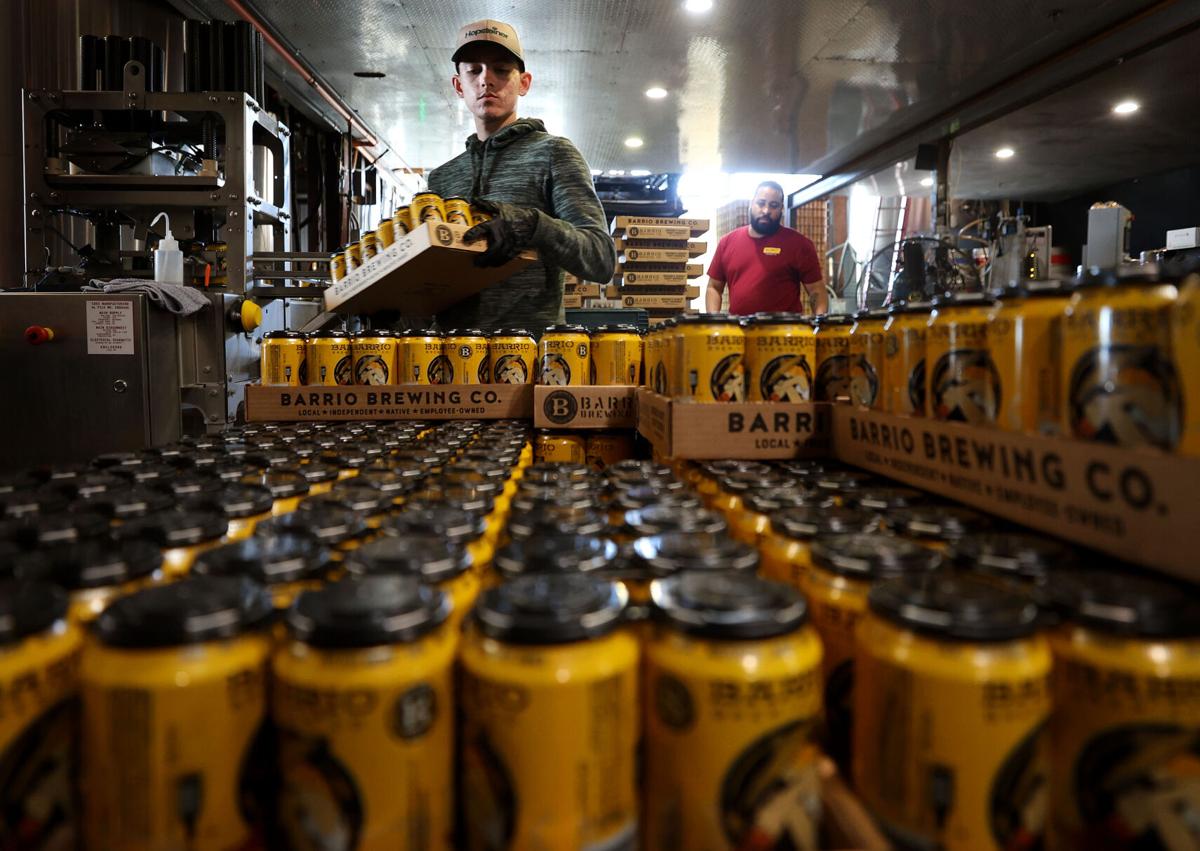

Cans of Barrio Blonde get filled during the canning process at Tucson’s Barrio Brewing.

Borderlands, which opened in 2010, took that step last September when it stopped canning its beers.

“We were losing money,” Teran said. “While it gave us brand exposure and we were able to get a lot more presence in the market, it didn’t make financial sense. We just weren’t making any money at that point.”

Barrio Brewing cans 45% of the 13,000 barrels of beer it produces annually, distributing Citrazona Indian Pale Ale, Hipsterville Hazy IPA and its popular Tucson Blonde to stores statewide. The brewery, the state’s oldest and fifth largest, was the first to can its beers back in 2013.

“At the time, canning wasn’t a popular thing,” said Barrio CEO Jaime Dickman. “It was more glass bottles.”

Because of its size, Barrio is able to lock in price contracts to soften the economic blow from price increases. Before the tariffs went into play, Barrio ordered three truckloads of pre-printed cans. That should be enough to take the brewery through the year, Dickman said, although they weren’t able to get as many Tucson Blonde cans as they will need. Blonde is the brewery’s most popular beer.

“That’s where we are going to take on these tariff costs is for the Blonde cans,” she said.

Barrio Brewing has no plans to cut back on its canning but it is looking at other steps in its beer-making process where it can cut costs. The goal, Dickman said, is to maintain the price point for consumers.

“It’s hard to raise prices when they already are spending $12 for a six pack when they can get a macro-brewed six pack for half the cost,” she said. “We are really trying to do whatever we can to keep our costs down.”

Pueblo Vida Brewing Company is hoping the impact from the tariff will sidestep them. They buy their cans from a manufacturer in Chicago that uses American aluminum, including recycled aluminum, said owner Kyle Jefferson.

So far, the company hasn’t heard if their supplier plans to raise prices, said Jefferson, who opened the brewery with Linette Antillon in 2014; they started canning their beers two years later.

Pueblo Vida, which brews 1,250 barrels a year, has created more than 250 unique cans in the past 8½ years, including its red and blue Wildcat Sonoran-style Cerveza, a collaboration with the University of Arizona. Roughly 60% of its sales are from canned beers sold locally at Total Wine & More, Sprouts and Whole Foods, which also carries the beers statewide.

Jefferson said any price increases will hurt his bottom line.

“Margins are thin and you can see that in food and beverage everywhere,” he said. “Any price increase that we get we’re trying to absorb because our F&B customers are struggling and our consumers are struggling.”

The margins are especially thin for newcomers like MotoSonora, which produces about 1,200 barrels a year.

The southside brewery, which just marked its fifth anniversary, kegs 75% of its beer for draft sales, including from its microbrewery at 1015 S. Park Ave. It cans the remaining 25%, paying an average 30 cents per can, and that beer often competes for consumer attention on store shelves alongside less expensive nationally known macrobrews.

“If I sell it to my distributor, he sells it to Whole Foods and it sits on a shelf,” DeConcini said. “We’ve been canning for four years. Had I to do it all over again, I wouldn’t have focused on (canning) so much knowing what I know now.”

Borderlands’ Teran is considering taking a page from the craft brewing industry’s past to navigate the future as he looks to bring back growlers.

“In reality, the whole canning business started in the pandemic, but before that growlers were the way to go,” said Teran, who has owned the brewery since 2018. “That was a pretty niche and cool thing about the craft brewing industry, which was different from the normal brewing industry.”