Many water officials have seen cloud seeding as one possible fix for the U.S. West’s drought, which has now stretched to 25 years and is believed to be the second worst in the past 1,200 years.

But after nearly 80 years of experiments, studies and government programs aimed at seeding clouds to boost rainfall and snowfall, a new federal study concludes it’s still not clear how effective the technology is.

The study from the congressional Government Accountability Office did find significant technological advances in cloud seeding, such as radar to track cloud movements and monitor clouds suitable for seeding.

But it says basic questions remain unanswered. Not least of those is how much of the rain or snow that is produced after clouds are seeded might have been produced without the seeding.

The report also raised concerns about whether other studies showing cloud seeding works were statistically insignificant.

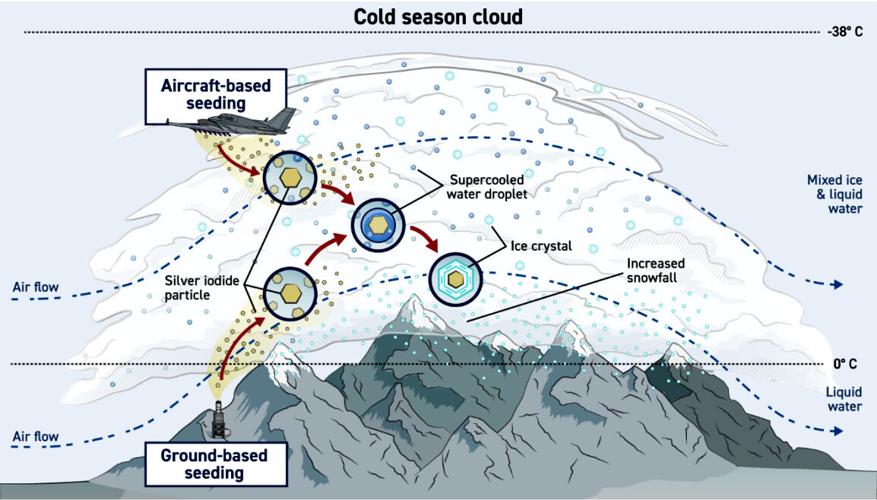

Cold season cloud seeding over mountains.

One reason it’s difficult to determine effectiveness is limited funding, said Karen Howard, the GAO study’s director. “Often, the kind of research that needs to be conducted is comparing one cloud to another and finding two clouds that are very similar. Then, you need to seed one and not the other to see how much rain they do produce. The problem is that costs money.”

Colorado River Basin’s needs

The unresolved questions mean “we have no estimate” of how much new water cloud seeding could put into the Colorado River Basin, said Howard, GAO’s director of science, technology assessment and analytics.

Some 40 million people in seven Western states, including Arizona, depend on the dwindling river for drinking water, irrigation and industrial use.

At the same time, many state agencies and other entities that practice or finance cloud-seeding work — including the Central Arizona Project — continue to vouch for its value, while acknowledging the uncertainties.

The CAP doesn’t operate any cloud-seeding projects within Arizona but does join other agencies in financing cloud-seeding programs in other states in the Colorado River’s Upper Basin. That’s where most of the river water bound for Phoenix and Tucson through CAP comes from.

A remote ground-based generator in Utah is used to disperse microscopic silver iodide particles into clouds to help seed them with the goal of increasing rain and snowfall.

The river is now entering its fourth year of water shortages for the Lower Basin states of Arizona, Nevada and California. The cutbacks will likely worsen when and if the states come to agreement on a long-term plan to bring the river into balance between supply and demand.

Creating an effective, basin-wide cloud-seeing program would require launching a number of seeding operations, Howard said.

“If you’re trying to add snowfall to the Rocky Mountain ranges, you’d need cloud-seeding operations at many locations in ranges. And all have to be successful,” she said.

Previous optimism

Her comments are far less optimistic than those made 10 to more than 55 years ago by other agencies and experts.

For example:

— In the late 1960s, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation estimated the potential for about 870,000 acre-feet annually from cloud seeding, or more than half the historic, pre-shortage supply of the Central Arizona Project. An acre-foot is enough to serve four typical Tucson households a year.

— In 1972, a group calling itself North American Weather Consultants estimated the West could reap up to 1.515 million acre-feet annually from cloud seeding for the Colorado River.

— As recently as 2006, the bureau said cloud seeding has the potential to produce up to 1 million acre-feet a year.

— In 2015, former CAP official Chuck Cullom said he envisioned cloud seeding ultimately producing 250,000 to 500,000 acre-feet a year.

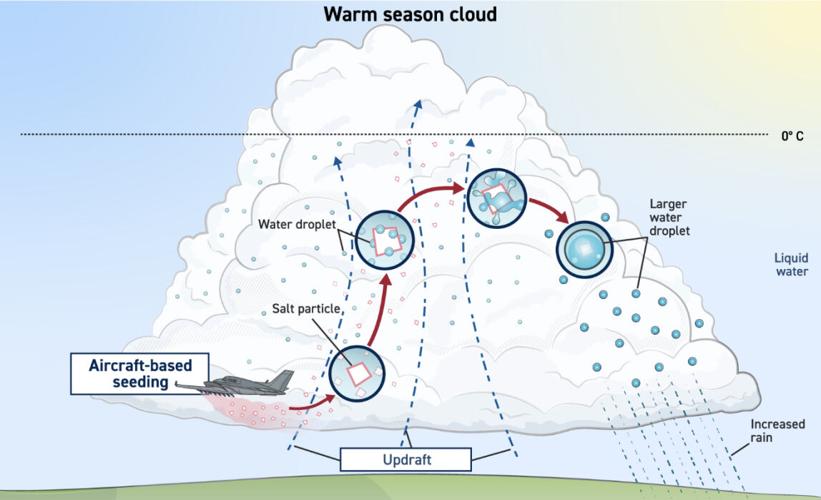

Warm season cloud seeding.

However, two past studies by the GAO in the 1970s and the National Academy of Sciences in 2003 also questioned how effective cloud seeding is. GAO officials said many of the concerns raised by those studies remain valid, although improved technology has addressed some of them.

Health effects also uncertain

Research on cloud seeding shows no sign of any negative environmental or public health effects from current levels of use of silver iodide, by far the most common agent used to seed clouds, the GAO study said. Silver iodide is an inorganic compound put into clouds.

It’s not known whether more widespread use of silver iodide would pose risks to public health or the environment, the study said. One reason for the uncertainty is that while silver iodide is nearly insoluble in water, when it does dissolve it releases a small number of silver ions. In large enough quantities, silver ions — a known antimicrobial substance — could have harmful effects on beneficial bacteria in the environment and water resources, the study said.

“If the use of cloud seeding technology increased significantly above current levels, the number of silver ions going into the environment would likely also increase. Research may be helpful to determine whether any health or environmental effects might occur from a significantly higher number of silver ions,” said the GAO’s Howard.

Other potential seeding agents — including liquid propane, other chemical salts such as calcium chloride, and biological agents — are less widely used, at least in the U.S,, GAO said. But new seeding agents may be subject to review by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Another uncertainty about seeding is its downstream effects, the GAO study said. Some research of cloud seeding has found it can potentially affect precipitation outside the area it’s intended to affect.

“But the extent and direction of these effects are unclear. For example, some studies found seeding may cause a small increase in precipitation outside the target area, while others suggest a small decrease is possible — but more study is needed to quantify the effect.”

In the eastern U.S., cloud seeding and other forms of weather modification are facing opposition not due to lack of effectiveness but out of fear they’re too effective in ways the critics don’t want.

Tennessee enacted legislation last April banning cloud seeding and other forms of weather modification. Backers of the ban particularly singled out “geoengineering,” a practice that aims to alter the weather on much larger scales and over a longer time period than cloud seeding. It’s particularly aimed at counteracting human-caused global warming.

Nine other Eastern states are considering similar bans, the GAO study found. Similar legislation was also just introduced in Arizona.

CAP pays for cloud seeding elsewhere

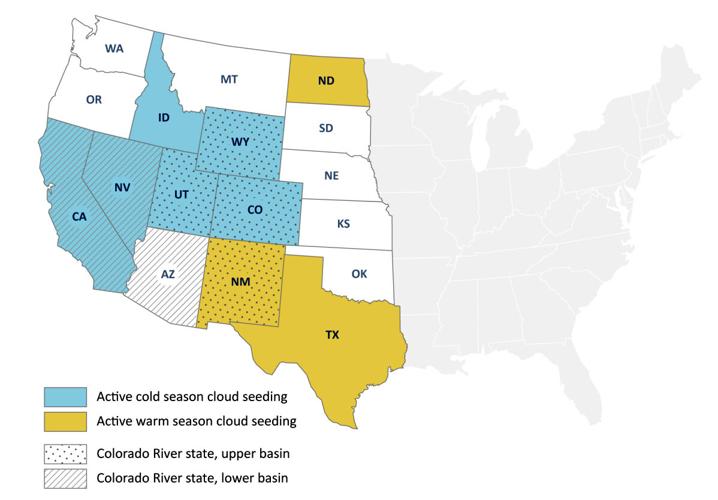

Nine Western states, including all seven Colorado River Basin states except Arizona, are currently engaged in active cloud seeding programs within their boundaries. Their goal is to try to induce more rain and snow into drought-stressed rivers and streams.

Utah provides by far the most financial support for cloud seeding, the report said. In 2023, Utah approved $12 million in one-time funding with an ongoing annual budget of $5 million. Other states typically provide a few million dollars or less annually, the report said.

Utah has been financing various cloud-seeding projects across the state since 1974. It estimates that overall, the seeding has increased river runoff statewide by up to 12%, or 186,000 acre-feet. That approaches the equivalent of two years’ supply for Tucson Water’s customers.

In Utah’s section of the Colorado River Basin, cloud seeding has boosted runoff by about 56,000 acre-feet annually, the Utah Department of Natural Resources reported in 2018. The average cost of the cloud seeding was a little less than $3 per acre-foot, far lower than most other water supplies, that study estimated.

“I agree that the evaluation of cloud seeding projects is very difficult, and the greatest challenge within the field (outside of public misinformation),” Jonathan Jennings, a meteorologist and cloud seeding coordinator for the state natural resource agency, wrote in an email to the Star. “However, I must not discount the quality work that has been done by programs in Utah, Wyoming, and Texas which have shown a strong indication of a 10-15% increase in precipitation.”

Jennings is also president of the nonprofit Weather Modification Association, which promotes “free exchange of accurate information regarding the efficacy, safety, methodology and cost-effectiveness of weather modification activities.”

The CAP actively participates in weather modification programs that include “certain cloud-seeding projects in the Upper Colorado River Basin” states of Wyoming and Colorado as well as Utah, said Vineetha Kartha, the agency’s Colorado River programs manager. Their purpose is also to generate more mountain rainfall and snowmelt to run into the Colorado.

The projects are coordinated with the North American Weather Modification Council, a nonprofit group whose stated mission is “to advance the proper use of weather modification technologies through education, promotion and research.”

Kartha didn’t comment on the new GAO study. But she acknowledged uncertainty with cloud seeding in that “weather/storms are innately chaotic, unique processes. They are not standardized.

“Every second of every day, the ebb & flow of the atmosphere is always something new that we have never seen before, so it is impossible to reliably quantify the precise benefit that any single seeding event will have,” she wrote in an email to the Star.

“This hasn’t stopped science from trying, and there seems to a healthy dose of skepticism, because we are still a long ways out from being able to make the call on exactly how much more snow we can expect to have generated at the end of a season,” Kartha said.

Broadly, the seeding CAP finances has been shown to produce a 5-15% increase in snowpack, the CAP said. But because runoff depends on much more than the amount of precipitation, “there are additional layers of ambiguity involved in its prediction,” the agency said.

“At present, we continue to focus on the positive outcomes in the research, and to learn how to adapt to (and even harness) the unique natural processes upon which our water supply depends,” she said.

The CAP, Southern Nevada Water Authority, and a California six-agency committee have an agreement to spend up to $500,000 each, annually, for Upper Basin projects. But because not all storms are good candidates for seeding — and because winters vary — seeding operations do not continue in perpetuity, and the CAP has yet to spend the full amount in a year.

For example, CAP contributed $366,508 to the program in 2023 and is anticipated to spend $341,373 for 2024.

The money goes toward an assortment of items, including seeding solution, remote generators, backpack generators, fuel for the generators and other equipment.

CAP funds the cloud seeding program because “we know that we are helping augment the snowpack to the extent possible,” Kartha said.

Idaho study shows both sides of debate

A cloud-seeding study that’s drawn considerable attention was a 2017 effort from Idaho that was jointly financed by the National Science Foundation and the Idaho Power Company.

The foundation has cited the study as “the most comprehensive evidence to date that cloud seeding can generate rain or snow.”

But David Verardo, a science foundation official, acknowledged that study’s conclusions were consistent with the GAO study’s findings that seeding has inconsistent results.

The study analyzed detailed observations from a cloud-seeding experiment that winter, using researchers from three universities and the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

It found “injecting clouds with silver iodide generated precipitation at multiple sites, sometimes creating snowfall where none had existed,” the science foundation, a federal agency, said in a 2020 news release.

But in response to questions from the Star, Verardo said the Idaho study and the GAO reports point to the need to better understand atmospheric circulation, chemistry and other mechanisms that come together to form precipitation. Verardo served last July on an expert panel GAO consulted with for its study.

“The process of natural precipitation is hugely complicated so replicating it requires us to know precisely how the process unfolds in nature. That is part of the challenge of cloud seeding as a technology,” said Verardo, the foundation’s program director for paleoclimatology.

Cloud seeding sometimes produces the precipitation that is expected and sometimes does not, Verardo added.

States with active cloud seeding programs in 2024.

“There is uncertainty in the planned precipitation outcomes and the role of research is to better understand the processes involved and narrow that uncertainty to some level acceptable for municipalities and utilities to consider cloud seeding as a potential tool in their toolbox,” he said.

Wide range of effectiveness found

The new GAO report stops well short of saying cloud seeding doesn’t work. In fact, it says researchers on that Idaho study were able to directly observe processes by which cloud seeding can work. The researchers observed the formation of ice crystals from “supercooled liquid water” in clouds after seeding and their fallout on the mountain surface — key documentation of the chain of events for this seeding approach.

Generally, over the past few decades, advances in computer models and radar and sensor technology have improved evaluations of cloud processes and may help improve understanding of cloud-seeding effects, the new study said.

But various cloud-seeding studies and programs still find a wide range of effectiveness. The World Meteorological Organization, for one, estimated a range of 0% to 20% depending on a number of factors, GAO’s Howard said.

“Even within a given state and a given operator, when they’re doing it over a number of years, not every cloud gets as much increases in precipitation as another cloud,” she said.

One thing researchers did notice in their study is that many states reduce funding for cloud seeding work when precipitation is good, but then boost their funding in a time of severe drought.

“That’s human nature, but during droughts you will get less precipitation,” Howard noted.

Amid two decades of drought, cloud seeding — using airplanes or ground equipment to waft rain-and-snow-making particles into clouds — is on the rise in the Rockies. Colorado has a long history of cloud seeding, said Scott Griebling, water resources engineer with the St. Vrain and Left Hand Water Conservancy District, which launched its first seeding program this winter near the Denver metro area. “All of those programs have been on the west part of the state. And this program is the first on the east part of the state.” No small part of the growth is due to intense pressure drought is placing on the Colorado River and its tributaries that supply water to millions of people from Wyoming to Los Angeles. But in the Rockies, cloud seeding these days has a full embrace from local and state officials eager for a not-too-expensive way to put more water in streams, rivers and especially the big Colorado River system reservoirs that hit record lows last year. Their approach: shoot silver iodide into clouds, where moisture binds to the particles, forms ice and falls as snow. That snowpack high in the mountains serves as year-round cold storage for water that's released as it melts.