Mika Gadsden is well versed in the electoral process, having run for mayor, served as a polling precinct clerk and worked as a political activist over the past decade.

But Gadsden said even she was having a hard time determining which congressional district she is slated to vote in later this year in South Carolina's Charleston County.

Her confusion stems from a process known as gerrymandering, in which political parties in power manipulate the boundaries of voting districts to gain an electoral upper hand.

The process can amount to an "assault on democracy," Gadsden said.

You may have heard of the word gerrymandering before but have never known what it means. Here’s a look at what gerrymandering means and why it is used in politics.

The effects of gerrymandering are neither new nor uncommon, but with Democrats and Republicans currently splitting control of Congress by the narrowest of margins, experts say a small number of pending redistricting battles and newly released maps could help determine which party holds the levers of power in the U.S. House of Representatives after this year's elections. The states where the stakes are highest include:

- South Carolina, where the U.S. Supreme Court is expected to decide soon whether to allow a new congressional map to stand.

- New York, where the state Legislature rejected this week the latest congressional map drawn by a bipartisan commission and adopted a new one.

- Wisconsin, where a recent lawsuit could lead to the redrawing of congressional maps.

- Louisiana, where a new map released in late January creates an additional majority-Black congressional district.

- North Carolina, where redistricting has been the subject of Supreme Court rulings and ongoing lower-court fights.

Wisconsin Gov. Tony Evers raises a bill that re-defines the state's legislative maps after signing it at the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison on Feb. 19.

South Carolina’s electoral maps — redrawn in 2021 — moved Gadsden and some 30,000 other Black voters out of a competitive district and into one that has been in Democratic hands for four decades.

The process, she said, has “sown seeds of confusion" and “really does demoralize a lot of people” who find their vote will carry less weight.

SC maps 'really an assault on democracy,' voter says

“What we see is that the powers that be have pretty much picked the winners for people,” Gadsden said. “It’s so undemocratic. It’s really an assault on democracy in general.”

The practice of moving electoral district boundaries to promote certain outcomes, such as increasing the odds that a certain party wins or reducing the voting power of particular groups of voters, is not a new part of our election system. Politicians have employed the tactic for centuries, and voting rights activists have been trying to combat it for about as long.

The back and forth has left courts to determine when such redistricting crosses a legal line.

After South Carolina’s governor signed the new maps into law, the state NAACP and a local voter sued, alleging that the new state map is an example of illegal gerrymandering that discriminates against those voters based on the color of their skin.

With that case now in the hands of the Supreme Court, the implications for Gadsden and the other voters in Charleston could be significant. Should the court decide the gerrymander was illegal, those Black voters will go back to casting their ballots for a seat that a Democrat held as recently as 2021, when Republican Rep. Nancy Mace won election.

Decisions in a few cases could have nationwide effect

And with Republicans holding a razor-thin majority in the U.S. House of Representatives, experts say the ramifications of that court decision and a handful of other pending cases that allege illegal gerrymanders could be felt nationwide.

Smith

“There are going to be some places where Democrats pick up a seat or two or, maybe in New York, three or four,” said Paul M. Smith, senior vice president of the nonpartisan Campaign Legal Center and a lawyer who has argued multiple landmark gerrymandering cases before the Supreme court. “In North Carolina, when the new Supreme Court there had the map redrawn, the Democrats lost two or three or four seats.

“So it may end up having a net effect that’s fairly modest across the country,” Smith said.

“But given how closely divided the House is, we might very well find that a decision or two here were decisive, because whichever party is in control next time might be in control (of the House) by about two seats.”

Candidates choose their voters when maps redrawn

Mitchell D. Brown, senior counsel for voting rights for the Southern Coalition for Social Justice, puts the problem of gerrymandering plainly.

It occurs, he said, when legislators are “choosing their voters, and voters are not choosing their legislators.”

“Our democracy is supposed to be of the people, by the people and for the people,” Brown said.

Brown

“But right now it’s of the elected officials, by the elected officials and for the elected officials.”

The anti-democratic effects of gerrymandering, Brown and other experts argue, are wide-ranging.

When individual voters see the power of their vote weaken as they are packed by party, race or other factors into districts designed to reliably elect candidates of a certain party, Brown said it tends to dampen voter interest in elections where outcomes seem preordained.

Voters also can be undermined by a gerrymandering tactic known as cracking, which involves splitting up groups of voters and assigning them to electoral districts that are safe for the party they don’t belong to.

However gerrymandering is implemented, Brown said, the result is it makes it harder for voters to hold politicians accountable at the ballot box. And when officials are less accountable to their constituents, he said, the effects are felt far beyond the polling precinct.

“The practical effect is there’s less representation,” Brown said. When gerrymandering is based on race, he added, “the needs of the Black community are not met because you have elected officials that don’t speak to the experience of the Black community.”

The creation of safe seats can also exacerbate partisan polarization and “push people to the extremes, politically,” said Smith, of the Campaign Legal Center, because politicians have to focus primarily on winning primaries, not general elections.

“And that,” Smith said, “pushes people toward the extreme right or the extreme left.”

Wonky shapes lead to shift in political power

While the problems with gerrymandering are easy to see, the practice is difficult to stop, according to Smith, who has spent decades trying to do so.

Despite repeated attempts to get the Supreme Court to find it illegal when an electoral map “is designed to guarantee one party wins most of the seats, even if they don’t get most of the votes,” Smith said the court determined in 2019 that such partisan gerrymandering is a political question that’s “too complicated for the federal courts to deal with.”

“And so,” he said, “you can’t go to federal court and challenge partisan gerrymandering.”

But the U.S. Supreme Court has affirmed the rights of state courts to combat partisan gerrymandering in maps drawn by state legislatures. Last year, the court ruled that the North Carolina courts can regulate redistricting to ensure it accords with the state constitution.

Cooper

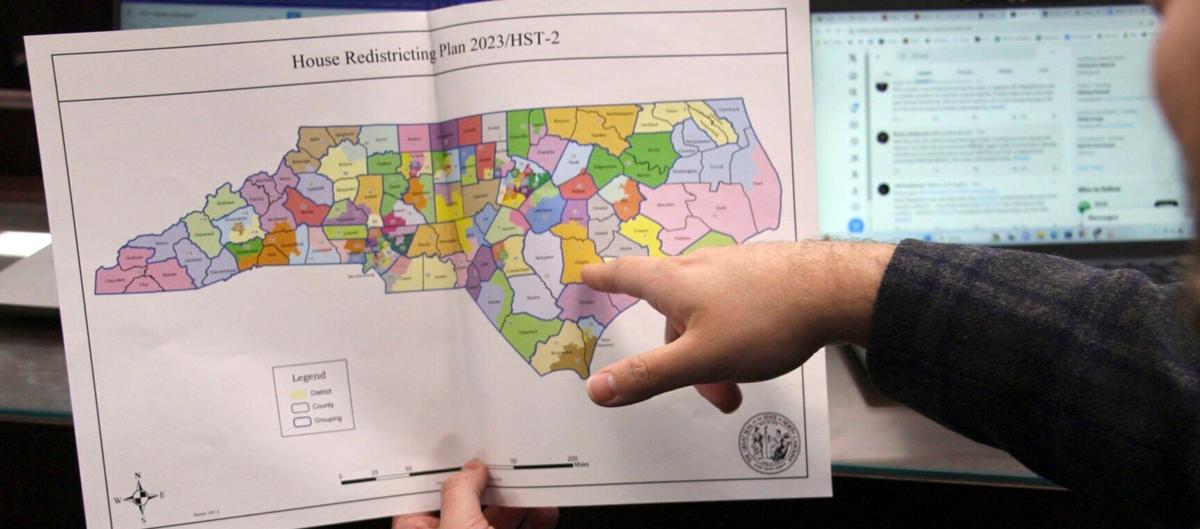

“North Carolina has really been ground zero for the redistricting and gerrymandering conversations nationwide,” said Chris Cooper, a political science professor at Western Carolina University.

The Supreme Court ruling leaves the partisan gerrymandering fight at a state level. In North Carolina, that allowed a new conservative state supreme court majority to reverse a previous ruling, allowing Republican-leaning redistricting maps to be implemented for the 2024 election, Cooper said. The court also ruled that political gerrymandering was not a question for state courts.

The fight over gerrymandering in North Carolina is nothing new but has increased in the past decade, Cooper said. Since 2010, the state has seen seven congressional district voting maps enacted, four of which were used in elections.

Texas maps reflect 'unbridled gerrymandering,' professor says

Jones

The change in gerrymandering after 2010 was seen in Texas as well, Rice University political science professor Mark Jones said. The state’s 2021 voting maps reflected “unbridled gerrymandering in a way that hadn't been the case in 2005 and 2011,” Jones said.

Congressional districts in Texas pack Democrats together, twisting and turning to form wonky shapes that span miles. In Texas, the redistricting has all but ensured a Republican hold in the state, Jones said. While gerrymandering might not always play a significant role in elections, in a year like 2024, when the election is close, a handful of seats could affect control, Jones said.

Gerrymandering takes some of the question out of elections, leaving some voters feeling disenfranchised, Jones said. The near-constant changes in North Carolina also make it difficult for voters to know who represents them at a state and national level, Cooper said. Despite challenges, Cooper says, it's unlikely anything will change in North Carolina.

The North Carolina House reviews copies of a map proposal for new state House districts during a committee hearing at the Legislative Office Building in Raleigh, N.C., on Oct. 19, 2023.

The latest maps in North Carolina, allowed by the state Supreme Court, are still being challenged in court, Cooper said. The most recent lawsuit, filed in December, alleges racial gerrymandering, the first case to do so for the current maps, he said.

“The stakes are too large for people to not at least try to overturn these maps,” Cooper said. “Both parties are challenging the maps. It’s very clear they know the maps mean power. It’s a convenient fiction — but a fiction — to say the people still get the final say.”

Courts can intervene if race main motive vs. politics

While state courts have become the main battleground over partisan gerrymandering, the U.S. Supreme Court has found that federal courts can get involved in race-based gerrymandering.

That’s based in part on the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause, which says states cannot undermine citizens’ rights, and in part on the Voting Rights Act, a 1965 law designed to ensure all citizens have an equal opportunity to participate in elections.

But to pursue cases under those provisions, a court has to determine, first, whether race was “the predominant motive in the minds of the people drawing the lines,” Smith said.

That can be tricky, especially when race seems to be used as a proxy for party, as often occurs with Black voters, who tend overwhelmingly to vote for Democrats. Brown said the difficulty in making distinctions between race and party means Black voters don’t have the same protections.

“All the legislature has to do is say, ‘Hey, we didn’t do this for racial reasons. We did this for partisan reasons,’” Brown said.

Courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, have heard several cases that hinge on such determinations. While many of its decisions were widely viewed as undermining legal protections for Black voters, the court surprised observers last year when it upheld a key piece of the Voting Rights Act that requires “states to create opportunities for voters of color to elect candidates of their choice when they’re faced with massive racially polarized voting, like in the South,” Smith said.

The effect of that decision will be felt in this year’s congressional election, because the ruling resulted in the drawing of a second Black-majority district in Alabama. That district is expected to elect a Democrat to Congress.

Decision helps cause of 'racial justice' in districting

It also means “there will be continued efforts to create majority-Black, majority-Latino districts in situations where, if you don’t, the majority white population will control all the districts,” Smith said. “So that was a very positive decision for those who believe in racial justice in districting.”

Brown said such protections are crucial, because, he argues, race is a factor even when legislators profess not to be considering it.

“To believe that a legislature can draw a race-blind map is farcical,” Brown said. “These people know where the Black voters are, where white voters are, where Latino voters are. To say something is race blind, you can draw your district by memory, and you know how to gerrymander. Race is always going to undergird what the legislature does, which is going to affect minority voters.”

Calhoun County, South Carolina, voters cast ballots on Feb. 24 in the Republican presidential primary at Calhoun County's Dixie precinct, located at the John Ford Community Center.

The South Carolina case currently pending in the U.S. Supreme Court hinges on whether the justices find politics or race influenced the district maps.

If justices rule the new electoral maps were drawn to advance a partisan advantage, the changes will be allowed to stand.

If the high court determines legislators were motivated by a desire to pack Black voters in a single safe district, the court could order maps to be redrawn.

Clyburn case complicates gerrymandering discussion

This distinction between race and politics has been further clouded by the findings that Rep. Jim Clyburn, the Black Democrat who has represented the state’s 6th Congressional District since 1993, worked with Republicans to move Black voters into his district in order to shore up his chances of reelection.

ProPublica examined Clyburn’s role in depth. A three-judge panel that found the new lines represented a racial gerrymander also described the congressman’s staff’s role in helping Republicans alter his district.

While a Republican who led the redistricting effort said he “received a map from the staff of Congressman James Clyburn and (that) he incorporated the Clyburn staff proposals into the final plan,” he also acknowledged making “dramatic changes” to the staff’s recommendations, court documents say.

Clyburn’s office has strongly denied that he participated in the state’s gerrymandering, but experts have long described an “unholy alliance” between Black Democratic lawmakers and Republican lawmakers to draw maps that create safe seats for the former at the expense of a broader advantage for the former.

Is there a fair solution to drawing districts?

While there’s no doubt legislators from both parties work behind the scenes to draw maps to their advantage, Smith said there isn't an obvious way to draw them objectively and fairly.

The challenge lies, in part, in how people tend to congregate geographically by party, which leads to what Smith calls “unintentional gerrymandering.”

“One of the things that is true of the way our country is set up is that Democrats tend to cluster themselves in cities,” he said. “And so if you draw maps without thinking of partisanship at all — just draw squares or whatever — you end up with more Republican seats than Democratic seats, even if it’s a 50-50 state, because the Democrats pack themselves into a smaller number of districts with really, really high percentages of Democrats.”

So although he said Republicans have “been in a better position to do more gerrymandering,” Smith said he doesn’t think they are more prone to it than Democrats.

As courts tangle over whether to allow legislators to move electoral lines and decide who elects whom, a growing number of states have taken such decisions out of their hands altogether through the formation of redistricting commissions.

Samuel Wang, a Princeton University professor who leads the Princeton Gerrymandering Project, said court victories and citizens initiatives have led to a sharp decline in the practice over the past decade.

Wang

“You look at the congressional level — the degree of gerrymandering in the U.S. House of Representatives compared to 10 years ago — the distortion is less than half what it was in 2012,” he said. “So things are getting better.”

But issues remain.

While the movement to create independent commissions “is spreading across the country,” Smith believes there’s “a natural limit on how far that can go because in about half the states, at least, in order to get a constitutional amendment on the ballot, it has to be passed twice by the legislature. And they don’t pass it.”

Are independent commissions better at drawing maps?

Though experts say commissions tend to make better maps than politicians, some have struggled, including in New York.

New York voters changed the state constitution to take redistricting out of the hands of the state legislature and into an independent commission. But the commission deadlocked on its first attempt, which gave the job of redistricting back to legislators. That Democrat-controlled body then drew its own maps, which were signed into law, promptly challenged in court and invalidated.

The state Supreme Court then appointed a special master to draw yet another new map, which was used for a 2022 election that saw Republicans make important gains in New York’s congressional races.

But Democrats have been fighting to allow the Independent Redistricting Commission to have another chance at redrawing the maps, and in December, the state Supreme Court ruled in their favor.

When that new map was released this month, little was different from the one used in 2022. Had the state Legislature approved that map, Republicans would have been expected to maintain their gains. But on Feb. 26, Democrats rejected the map. Two days later, the state Legislature adopted a slightly different map designed to help Democrats pick up seats in a small number of key battleground U.S. House districts without drawing further court challenges.

Congress seen as unlikely to act on redistricting rules

Ultimately, Smith and others say, comprehensive change to the nation’s redistricting rules would have to come from the U.S. Congress itself. But that, Smith said, is unlikely anytime soon.

“Congress is the place where a lot of the problems with our democracy could get fixed,” Smith said. “It’s just, you’ve gotta get a majority in both houses – and a filibuster-proof majority at that — who really want to fix them, and that’s not easy. We don’t have that now.”

That leaves voters like Gadsden, in Charleston, waiting for court decisions and new maps that will decide where they vote, influence who wins their local elections and help determine who controls a bitterly divided Congress.

Gadsden views the situation as an “alarming” part of “a larger assault on peoples’ access to their own democracy.”

“It seems like the old guard within the establishment really has worked hard to maintain a level of power that doesn’t serve the voter at all,” she said. “It really does not serve the voter.”

It also does not serve democracy, Wang said.

“It is possible through legislative jiggery-pokery to gain an advantage that could never be gotten through any amount of campaigning,” Wang said. “So at the level of national power, it actually could be quite consequential.”