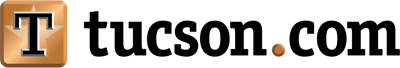

The message is hammered over and over, in news conferences, hearings and executive orders: President Donald Trump and his health secretary, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., say they want the government to follow “gold standard” science.

Scientists say the problem is that they are often doing the opposite by relying on preliminary studies, fringe science or just hunches to make claims, cast doubt on proven treatments or even set policy.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention building in Atlanta

The nation's top public health agency recently changed its website to contradict the scientific conclusion that vaccines do not cause autism. The move shocked health experts nationwide.

Dr. Daniel Jernigan, who resigned from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in August, recently said that Kennedy seems to be “going from evidence-based decision making to decision-based evidence making.”

It was the latest example of the Trump administration's challenge to established science.

In September, the Republican president gave out medical advice based on weak or no evidence. Speaking directly to pregnant women and to parents, he told them not to take acetaminophen, the active ingredient in Tylenol. He repeatedly made the fraudulent and long-disproven link between autism and vaccines, saying his assessment was based on a hunch.

“I have always had very strong feelings about autism and how it happened and where it came from,” he said.

At a two-day meeting this fall, Kennedy’s handpicked vaccine advisers to the CDC raised questions about vaccinating babies against hepatitis B, an inoculation long shown to reduce disease and death drastically.

“The discussion that has been brought up regarding safety is not based on evidence other than case reports and anecdotes,” said Dr. Flor Munoz, a pediatric infectious disease expert at Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children’s Hospital.

During the country's worst year for measles in more than three decades, Kennedy cast doubt on the measles vaccine while championing unproven treatments.

Scientists say the process of getting medicines and vaccines to market and recommended in the United States has, until now, typically relied on gold standard science. The process is so rigorous and transparent that much of the rest of the world follows the lead of American regulators.

U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. speaks during the Western Governors' Association meeting Nov. 20 in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The quest for the best possible evidence

The gold standard can differ because science and medicine are complicated and everything cannot be tested the same way. The term simply refers to the best possible evidence that can be gathered.

“It completely depends on what question you’re trying to answer,” said Dr. Jake Scott, an infectious disease physician and Stanford University researcher.

Many types of studies aim to gather evidence, the most rigorous being the randomized clinical trial.

It randomly creates two groups of subjects that are identical in every way except for the drug, treatment or other question being tested. Many are “blinded studies,” meaning neither the subjects nor the researchers know who is in which group.

It is not always possible or ethical to conduct these tests. This is sometimes the case with vaccine trials, “because we have so much data showing how safe and effective they are, it would be unethical to withhold vaccines from a particular group,” said Jessica Steier, a public health scientist and founder of the Unbiased Science podcast.

Studying the long-term effect of a behavior can be impossible. For example, scientists could not possibly study the long-term benefit of exercise by having one group not exercise for years.

Instead, researchers must conduct observational studies, where they follow participants and track their health and behavior without manipulating any variables. Such studies helped scientists discover that fluoride reduces cavities.

But the studies have limitations because they can often only prove correlation, not causation. For example, some observational studies raised the possibility of a link between autism risk and using acetaminophen during pregnancy, but more have not found a connection. The big problem is that those kinds of studies cannot determine if the painkiller made a difference or if it was the fever or other health problem that prompted the need for the pill.

Real world evidence can be especially powerful

Scientists can learn even more when they see how something affects a large number of people in their daily lives.

That real-world evidence can be valuable to prove how well something works — and when there are rare side effects that could never be detected in trials.

Such evidence on vaccines has proved useful in both ways. Scientists now know there can be rare side effects with some vaccines and can alert doctors to be on the lookout. The data proved that vaccines provide extraordinary protection from disease. For example, measles was eliminated in the U.S. but it still pops up among unvaccinated groups.

That same data proves vaccines are safe.

“If vaccines caused a wave of chronic disease, our safety systems — which can detect 1-in-a-million events — would have seen it. They haven’t,” Scott told a U.S. Senate subcommittee in September.

The best science is open and transparent

Simply publishing a paper online is not enough to call it open and transparent. Specific things to look for include:

- Researchers set their hypothesis before they start the study and do not change it.

- The authors disclose their conflicts of interest and their funding sources.

- The research has gone through peer review by subject-matter experts who have nothing to do with that particular study.

- The authors show their work, publishing and explaining the data underlying their analyses.

- They cite reliable sources.

This transparency allows science to check itself. Dr. Steven Woloshin, a Dartmouth College professor, has spent much of his career challenging scientific conclusions underlying health policy.

"I'm only able to do that because they're transparent about what they did, what the underlying source resources were, so that you can come to your own conclusion," he said. "That's how science works."

Know the limits of anecdotes and single studies

Anecdotes may be powerful. They are not data.

Case studies might even be published in top journals, to help doctors or other professionals learn from a particular situation. But they are not used to make decisions about how to treat large numbers of patients because every situation is unique.

Even single studies should be considered in the context of previous research. A new one-off blockbuster study that seems to answer every question definitively or reaches a conclusion that runs counter to other well-conducted studies needs a very careful look.

Uncertainty is baked into science.

"Science isn't about reaching certainty," Woloshin said. "It's about trying to reduce uncertainty to the point where you can say, 'I have good confidence that if we do X, we'll see result Y.' But there's no guarantee."