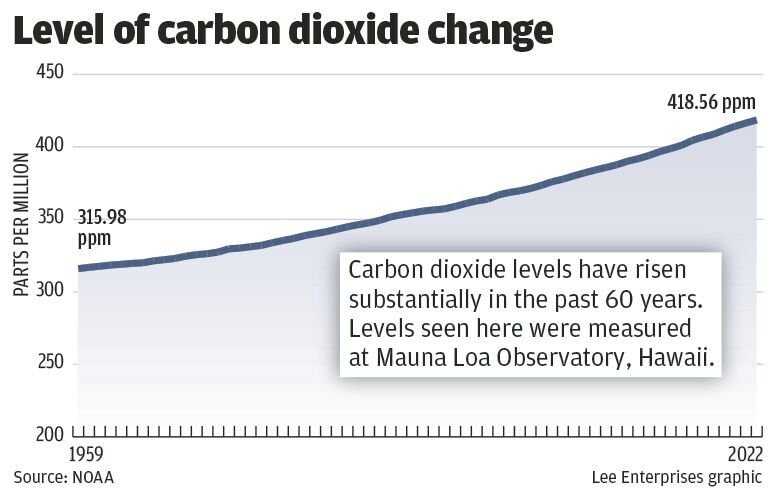

The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has climbed 33 percent since the late 1950s, an unprecedented spike in all of human history. Analyzing air bubbles trapped in ancient Antarctic ice, we know that the level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere has not been this high for at least 800,000 years. Other geologic indicators suggest even longer.

Direct measurements show the concentration has climbed to 420 molecules of carbon dioxide for each million molecules of air (parts per million). Increasing about 2 ppm every year, its connection to human activities is well understood. The chemical signature of the carbon shows it is not from volcanoes, and it has coincided with a very small, but detectable decrease in oxygen. This tells us that the increase comes from the massive burning of carbon — fossil fuels.

Further analysis of those bubbles shows a natural fluctuation of carbon dioxide during the last 800,000 years, back and forth between about 180 and 300 ppm. These fluctuations closely match the periods that Earth has been in and out of ice ages, which are triggered by small changes in Earth’s orbit around the sun and how it is tilted on its axis.

These small changes in the orbit and tilt affect how the sun’s energy is distributed across the planet. When coming out of an ice age, this change first begins to warm the oceans directly, and because warmer water cannot hold as much carbon dioxide as colder water, the gas escapes from the ocean into the atmosphere, intensifying any initial warming from the sun, and causing planetary temperatures to climb further.

In this way, carbon dioxide is like a thermostat. And like setting a thermostat in your home, the result is not instantaneous warming. Unlike popular cultural movies like “The Day After Tomorrow,” the change to a warmer climate does not happen in a couple of weeks.

When occurring naturally, the changes take hundreds, if not thousands of years. For example, the last ice age peaked about 20,000 years ago and ended about 12,000 years ago. Once it ended, humans began to develop agriculture and started forming societies, paving the way to the modern world.

But in the last couple of decades, the global temperature has only begun to respond to the dramatic surge in carbon dioxide. So even if all new carbon dioxide emissions were to instantaneously stop, the temperature would continue to rise for decades to come.

Small but mighty

Carbon dioxide is a very tiny part of the overall atmosphere, but it punches well above its weight.

Like all molecules, carbon dioxide vibrates. And because it has three atoms in its molecule, it can vibrate in three dimensions, so the molecule absorbs more energy to allow for those extra vibrations. The other two main gasses in the atmosphere, nitrogen and oxygen, have only two molecules each (N2 and O2), so they only vibrate in one dimension, and do not absorb nearly the amount of energy as a carbon dioxide molecule.

The end result is a warmer atmosphere for a small increase in carbon dioxide, and this has led to its moniker as a greenhouse gas.

The issue with carbon dioxide is its lifetime in the atmosphere, as the natural processes that remove it from the atmosphere can take centuries. And while there are some mechanical ways to remove carbon dioxide from the air, nothing has been developed to remove it at the scale needed to affect its total concentration in the atmosphere.

Not to be forgotten, water vapor (H20) is another important greenhouse gas, but unlike carbon dioxide, the atmosphere removes it via precipitation, and its concentration is far more dependent on the temperature of the surrounding air. Effectively, warmer air holds more water vapor, whereas carbon dioxide has no such dependency.

Small amounts of a gas may not seem to matter, but consider another gas — ozone. At its highest concentration in the stratosphere, ozone molecules total only about 10 ppm. This means that there is 40 times more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere than ozone, and yet that tiny amount of ozone absorbs nearly all of the highest energy ultraviolet rays from the sun, enabling both animal and plant life as we know it on Earth to flourish.

Current global policies put us on track for about 5.5 degrees Fahrenheit of warming in the next 75 years, but there is a lot of wiggle room in that value, depending on whether or not actual emissions match global policies. Other gases, like methane and nitrous oxides, are also important. But when it comes to sheer volume and lifetime, carbon dioxide is the key to the planetary warming problem.