African-American women have been a presence on the Western frontier for over 300 years, many of them as chattel of white slaveholders. During the turmoil of the Civil War, both men and women fled the South seeking opportunities in the loosely woven fabric of Western communities.

Elizabeth Hudson Smith arrived in Wickenburg in 1897. She and her husband, Bill, easily blended into the small mining community that already consisted of Mexicans, Indians, Asians and European-Americans.

Little is known of Elizabeth’s early life. She was born in Alabama sometime around 1870, the daughter of freed slaves. On Sept. 28, 1896, she married Bill Smith, a porter on the Santa Fe, Prescott and Phoenix Railroad.

When the Smiths arrived in Wickenburg, they took rooms at the Baxter Hotel, a dilapidated adobe structure built in the 1860s that stood about as steady as a drunken cowboy on Saturday night.

Owner Richard Baxter despaired of finding a competent cook for his old boarding house, and with his clientele threatening to lynch him for lousy service and almost indigestible food, he hired Elizabeth and Bill to cook, clean and manage the place.

Elizabeth apparently was highly educated, but where she went to school remains a mystery.

A 1962 Wickenburg Sun article claimed she graduated from Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, but school records do not list her.

Another story said she attended school in New Orleans, but again, no records can be found of her enrollment. Somewhere she acquired an acute business sense along with an adept knowledge of French.

After several years of successfully running the Baxter Hotel, the Smiths were asked by Santa Fe Railroad officials to establish a second hotel closer to the train station on Wickenburg’s Railroad Street (now Frontier Street). Dining cars were not yet part of train travel, and passengers needed a place to eat and stay overnight before continuing their journeys.

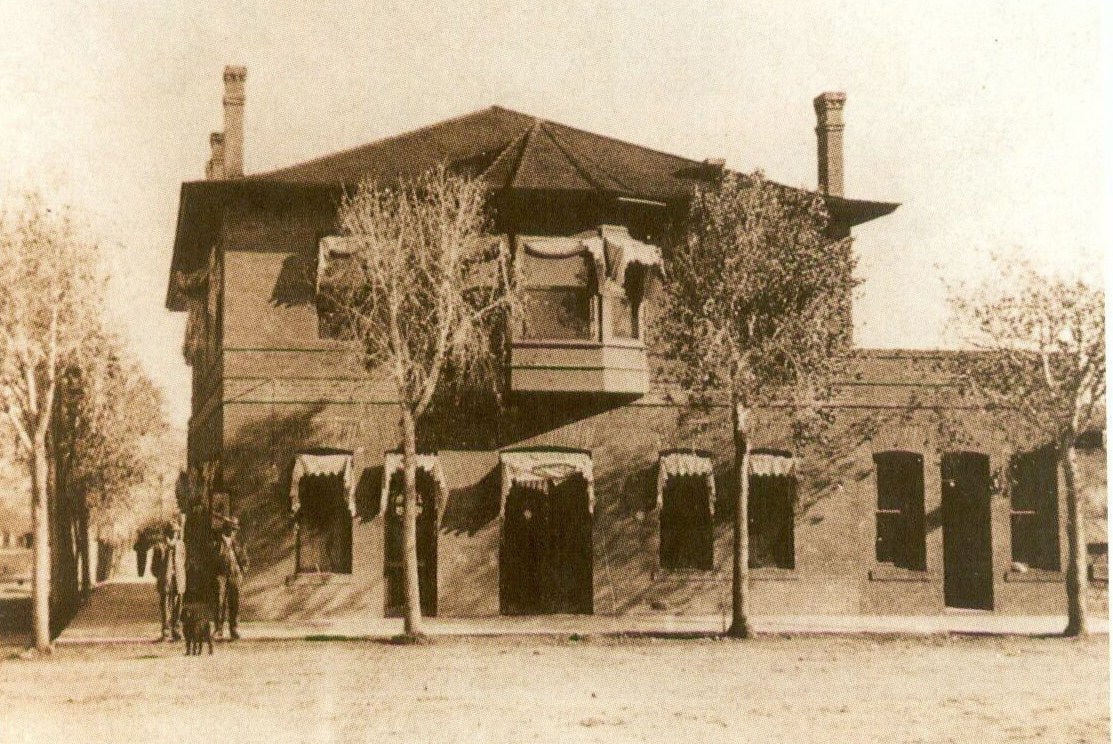

Phoenix architect James Creighton designed the building that would become the first brick structure in Wickenburg. Twelve-inch-thick walls blocked out the summer sun while an array of fireplaces kept rooms warm during winter months. Six giant chimneys welcomed those entering town, and wood cook stoves heated up the succulent repasts for which Elizabeth became renowned.

Elizabeth and Creighton designed a cross embedded in the lobby floor of the Vernetta. Both were co-founders of Wickenburg’s Community Church, later known as the First Presbyterian Church.

Opening in September 1905, Elizabeth advertised the Vernetta Hotel, named after Bill’s mother, who had provided the capital needed for this expensive endeavor, as having “lovely rooms — quiet and well-ventilated.” Accommodating about 50 guests, the Arizona Journal Miner touted the establishment as “the finest in town.”

Railroad officials were so delighted with the new hotel that they built a walkway from the train station right to the Vernetta’s front door. Passengers had plenty of time to down a drink in the hotel’s Black and Tan Saloon or partake of some of Elizabeth’s fine dining before continuing their journey. Those who stayed overnight delighted in the clean rooms and excellent service.

A bank was added to the lobby along with a post office and radio repair shop. The hotel provided a place for civic meetings and local entertainment. Elizabeth brought in musicians to entertain her guests and play the grand piano she placed in the lobby.

By 1909, she was engaging traveling shows to play in the backyard of the hotel until she later built an opera house in town. She even did a little acting herself. An avid bridge player, she invited townswomen to play cards in the lobby so she could participate whenever her duties allowed. She was always included in town social events and family celebrations.

People came from miles around to partake of Elizabeth’s feasts and enjoy an evening of entertainment. With her knowledge of the French language, she was soon teaching classes.

As time passed, Bill Smith had less and less to do with the hotel. Disappearing for days, sometimes weeks, Elizabeth eventually divorced him. Bill remained a drifter and died in California in 1926.

Along with her opera house, Elizabeth owned a ranch that provided livestock for the hotel’s kitchen. She fed her guests vegetables and fruits grown on her farm by the Hassayampa River. And every child in town knew that if they hung out near the back door of the Vernetta, they might walk away with some of Elizabeth’s homemade bread or, even better, one of her legendary chocolate-chip cookies.

Acquiring about 12 rental houses, a restaurant, barbershop and about 10 mining claims, Elizabeth became a leading figure in the community and her success contributed to the economic growth of the town. More than one miner was grubstaked through Elizabeth’s generosity.

Wickenburg developed into an industrious, thriving community, but changes brought new, sometimes pernicious, ideas into town.

The Great Depression of the 1920s intensified bias against black workers as everyone competed for jobs. Elizabeth’s hotel suffered when newcomers avoided the black-run business. She was often presumed to be the hotel maid.

Local women no longer met in the lobby to play cards, and Elizabeth was asked to leave the Presbyterian Church she helped establish years before. She became a stranger among old friends.

Elizabeth struggled to keep the Vernetta open until she died March 25, 1935, at the age of 65. The next day, the Vernetta dining room closed forever.

The Hassayampa Sun hailed Elizabeth’s “many deeds of kindness to the community,” but the town refused to allow her to be buried in the whites-only cemetery. She is buried with unknown miners, Mexicans and Chinese in the Garcia Cemetery on the outskirts of town.

Today, the Vernetta Hotel is known as the Hassayampa Building and is on the National Registry of Historic Buildings. The giant chimneys were destroyed years ago, but the thick brick walls and cross-designed floor remain as a tribute to the enterprising woman who brought a semblance of unity to a tiny desert town on the Arizona frontier, if just for a little while.