When E. Edgar Guenther knocked on Minnie Knoop’s door on Thanksgiving Day 1910, he had the most important question of his life to ask. Since he had only been seeing her a short while, he had no idea if she would agree to his bold proposition.

Minnie opened the door, and Edgar had only a moment to pose his question: “I just accepted a call to go to Arizona to the Apache Indians, and I want to know if you would go along.” Minnie was running late to sing at Thanksgiving services and hurriedly replied, “Oh yes, sure, but right now I have to go to church,” and off she dashed.

Eighty-six-year-old Minnie Knoop Guenther laughed when she recalled the long-ago proposal, saying neither she nor Edgar had any idea what was in store for them when they arrived in the Arizona Territory.

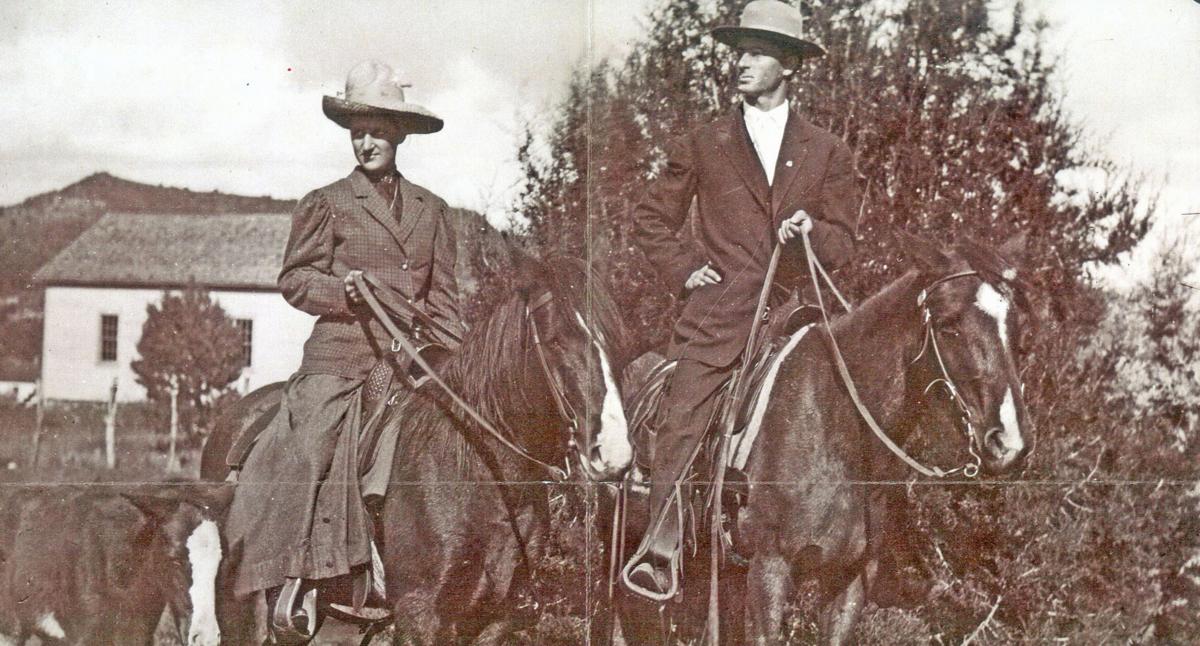

Born in Neilsville, Wisconsin, on July 12, 1890, Minnie worked her way through Cream City Business College in Milwaukee by dipping chocolates at a candy factory and tying bows and rosettes at a department store. She was 20 years old when she married 25-year-old Edgar Guenther, a Lutheran seminary student, on Dec. 28, 1910. Two weeks later, they were on their way to East Fork and the White Mountain Apache settlement.

More than 2,000 Apaches lived in the White Mountain area. Edgar had been sent to East Fork to start a mission school, and the first task the Guenthers faced was finding students, since most of the children attended government boarding schools. They finally rounded up a handful of children and converted a room in their small church into a classroom. Minnie set up a dining hall in another room, turning out hot meals for the students.

Edgar spent his evenings building desks and chairs, while Minnie typed the next day’s lessons. She patterned exercises after familiar Apache stories and illustrations the children understood and enjoyed. The Guenthers did not speak Apache and only a handful of Apaches knew English, but by the end of the first year, everyone was conversing to some degree.

Minnie gave birth to the first of her nine children in February 1912 with only Edgar to help her and a cowboy to hold her hand. Little Winonah was securely strapped into an Apache cradleboard and parked in a corner while Minnie prepared lessons and taught, cooked school lunches, held Sunday school classes and played the organ during church services. Those cradleboards, Minnie said, “were so much better than the plastic cradles of today. The baby is protected from the sun and wind and is securely strapped in.”

One day while Minnie was teaching, an Apache woman walked into the schoolroom. She picked up Winonah and headed for the Guenther house to clean and cook while cooing over the infant. She was a Chiricahua Apache who at one time ran with Geronimo’s band, known only by her identification number — B-3. The Guenthers had befriended B-3 when her daughter was dying, and the woman had come to return the kindness. Minnie and Edgar addressed her as “my mother,” which in Apache is pronounced “shi ma,” and that became her name. Shima stayed with the Guenthers, tending to their children until her death in 1945.

During the winter of 1914-15, whooping cough and pneumonia spread across the Apache reservation. Many died before the Guenthers reached them with what little aid they could supply. Edgar trapped skunks, rendered the fat and mixed it with turpentine and coal oil to use as a poultice. To give the concoction a pleasant odor, Minnie added a few drops of her perfume. They cut up clothing to use as chest pads, but when that ran out, they sacrificed their long underwear for dressings.

Four years later, an influenza outbreak hit the Apaches hard. The Guenthers closed the school and set out to help their neighbors. One of the many they treated was Chief Alchesay, who had served as a scout during the Apache uprisings and received the Medal of Honor for his bravery. Alchesay became such a trusted friend of the Guenthers that when Minnie gave birth to her sixth child in 1923, he insisted the boy bear his name. Arthur Alchesay Guenther followed in his father’s footsteps as a Lutheran minister.

During the chief’s last days, Minnie brought her organ to his home and sang hymns.

“I cannot understand the words you sing,” he told her, “but the music brings tears to my eyes and joy to my heart.”

After Edgar was appointed superintendent of missions for the San Carlos and Fort Apache reservations, the Guenthers moved to Whiteriver. The Lutheran Church started an orphanage for Apache children and often Minnie bundled up the little ones and cared for them in her own home. Three remained as part of the Guenther family.

Minnie was instrumental in sending many Apache youngsters with physical problems to Phoenix for treatment and personally arranging for surgery to possibly correct their disabilities.

Along with teaching classes and conducting church services at Fort Apache, Whiteriver and Canyon Day, the Guenthers held meetings at Apache campsites. Edgar would look for a place to hold service while Minnie set up her portable pump organ to lead the congregation in song.

In April 1961, more than 1,500 people gathered to honor the Guenthers with a golden anniversary celebration. That same year, on May 31, Edgar died.

Minnie’s children urged her to leave the reservation, but she refused. The Apaches were her neighbors and kept an eye on her.

Through the years, she had purchased an array of Native arts and crafts: medicine beans, cradleboards, baskets, headdresses, cowhide war shields, war bonnets and clubs filled her home. Her collection is housed at Tucson’s Arizona State Museum and is considered one of the most prominent collections of Native artistry.

In 1967, the Lutheran Ladies’ Aid Society nominated Minnie as Arizona Mother of the Year. After winning the Arizona prize, she headed to New York City to compete for the National title. To her surprise, Minnie was selected American Mother of the Year.

Minnie died in Whiteriver on Jan. 8, 1982, at the age of 91.

When asked about the Apaches she knew so well, she never hesitated. “We trusted every Indian,” she replied. “If they made a promise, they kept it.”