FILE - In this Aug. 2, 2018, file photo, a protester holds a Q sign as he waits in line with others to enter a campaign rally with President Donald Trump in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)

Conspiracy theories have been around for centuries, from witch trials and antisemitic campaigns to beliefs that Freemasons were trying to topple European monarchies. In the mid-20th century, historian Richard Hofstadter described a “paranoid style” that he observed in right-wing U.S. politics and culture: a blend of “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy.”

But the “golden age” of conspiracy theories, it seems, is now. On June 24, 2022, the unknown leader of the QAnon conspiracy theory posted online for the first time in over a year. QAnon’s enthusiasts tend to be ardent supporters of Donald Trump, who made conspiracy theories a signature feature of his political brand, from Pizzagate and QAnon to “Stop the Steal” and the racist “birther” movement. Key themes in conspiracy theories – like a sinister network of “pedophiles” and “groomers,” shadowy “bankers” and “globalists” – have moved into the mainstream of right-wing talking points.

Much of the commentary on conspiracy theories presumes that followers simply have bad information, or not enough, and that they can be helped along with a better diet of facts.

But anyone who talks to conspiracy theorists knows that they’re never short on details, or at least “alternative facts.” They have plenty of information, but they insist that it be interpreted in a particular way – the way that feels most exciting.

My research focuses on how emotion drives human experience, including strong beliefs. In my latest book, I argue that confronting conspiracy theories requires understanding the feelings that make them so appealing – and the way those feelings shape what seems reasonable to devotees. If we want to understand why people believe what they believe, we need to look not just at the content of their thoughts, but how that information feels to them. Just as the “X-Files” predicted, conspiracy theories’ acolytes “want to believe.”

Our desire to feel a certain way can drive our beliefs. Olexandr Nitsevych/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Our desire to feel a certain way can drive our beliefs. Olexandr Nitsevych/iStock via Getty Images Plus

Thinking and feeling

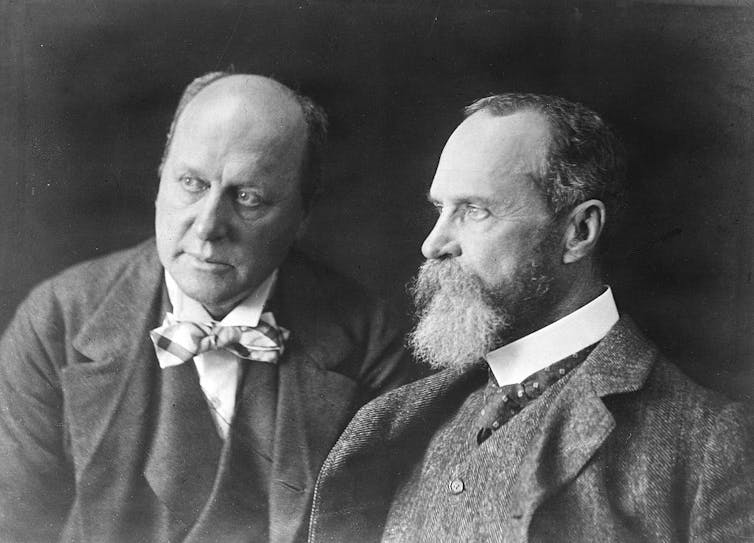

Over 100 years ago, the American psychologist William James noted: “The transition from a state of perplexity to one of resolve is full of lively pleasure and relief.” In other words, confusion doesn’t feel good, but certainty certainly does.

He was deeply interested in an issue that is urgent today: how information feels, and why thinking about the world in a particular way might be exciting or exhilarating – so much so that it becomes difficult to see the world in any other way.

James called this the “sentiment of rationality”: the feelings that go along with thinking. People often talk about thinking and feeling as though they’re separate, but James realized that they’re inextricably related.

For instance, he believed that the best science was driven forward by the excitement of discovery – which he said was “caviar” for scientists – but also anxiety about getting things wrong.

Psychologist William James, right, next to his brother, the famous novelist Henry James. Bettmann/Bettmann via Getty Images

Psychologist William James, right, next to his brother, the famous novelist Henry James. Bettmann/Bettmann via Getty Images

The allure of the 2%

So how does conspiracy theory feel? First of all, it lets you feel like you’re smarter than everyone. Political scientist Michael Barkun points out that conspiracy theory devotees love what he calls “stigmatized knowledge,” sources that are obscure or even looked down upon.

In fact, the more obscure the source is, the more true believers want to trust it. This is the stock in trade of popular podcast “The Joe Rogan Experience” – “scientists” who present themselves as the lone voice in the wilderness and are somehow seen as more credible because they’ve been repudiated by their colleagues. Ninety-eight percent of scientists may agree on something, but the conspiracy mindset imagines the other 2% are really on to something. This allows conspiracists to see themselves as “critical thinkers” who have separated themselves from the pack, rather than outliers who have fallen for a snake oil pitch.

One of the most exciting parts of a conspiracy theory is that it makes everything make sense. We all know the pleasure of solving a puzzle: the “click” of satisfaction when you complete a Wordle, crossword or sudoku. But of course, the whole point of games is that they simplify things. Detective shows are the same: All the clues are right there on the screen.

Powerful appeal

But what if the whole world were like that? In essence, that’s the illusion of conspiracy theory. All the answers are there, and everything fits with everything else. The big players are sinister and devious – but not as smart as you.

QAnon works like a massive live-action video game in which a showrunner teases viewers with tantalizing clues. Followers make every detail into something profoundly significant.

When Donald Trump announced his COVID-19 diagnosis, for instance, he tweeted, “We will get through this TOGETHER.” QAnon followers saw this as a signal that their long-sought endgame – Hillary Clinton arrested and convicted of unspeakable crimes – was finally in play. They thought the capitalized word “TOGETHER” was code for “TO GET HER,” and that Trump was saying that his diagnosis was a feint in order to beat the “deep state.” For devotees, it was a perfectly crafted puzzle with a neatly thrilling solution.

It’s important to remember that conspiracy theory very often goes hand in hand with racism – anti-Black racism, anti-immigrant racism, antisemitism and Islamophobia. People who craft conspiracies – or are willing to exploit them – know how emotionally powerful these racist beliefs are.

It’s also key to avoid saying that conspiracy theories are “simply” irrational or emotional. What James realized is that all thinking is related to feeling – whether we’re learning about the world in useful ways or whether we’re being led astray by our own biases. As cultural theorist Lauren Berlant wrote in 2016, “All the messages are emotional,” no matter which political party they come from.

Conspiracy theories encourage their followers to see themselves as the only ones with their eyes open, and everyone else as “sheeple.” But paradoxically, this fantasy leads to self-delusion – and helping followers recognize that can be a first step. Unraveling their beliefs requires the patient work of persuading devotees that the world is just a more boring, more random, less interesting place than one might have hoped.

Part of why conspiracy theories have such a strong hold is that they have flashes of truth: There really are elites who hold themselves above the law; there really is exploitation, violence and inequality. But the best way to unmask abuses of power isn’t to take shortcuts – a critical point in “Conspiracy Theory Handbook,” a guide to combating them that was written by experts on climate change denial.

To make progress, we have to patiently prove what’s happening – to research, learn and find the most plausible interpretation of the evidence, not the one that’s most fun.

___

Donovan Schaefer does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

___

From serious to scurrilous, a look at some Jimmy Hoffa theories

Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: Hoffa was killed on the orders of alleged New Jersey mob figure Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano. His body was “ground up in little pieces, shipped to Florida and thrown into a swamp."

Who put it forth: Self-described mafia murderer Charles Allen, who served prison time with Hoffa and participated in the federal witness-protection program, told the story to a U.S. Senate committee in 1982.

Outcome: The FBI never found enough evidence to support the claim and questions were raised about Allen trying to sell the story to make money.

Stadiums US NJ New York Giants

Updated

Theory: Probably the most infamous had Hoffa buried under Section 107 of Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, New Jersey.

Who put it forth: Self-described hit man Donald “Tony the Greek” Frankos in a 1989 Playboy magazine interview.

Outcome: The FBI found nothing to support the claim and didn’t bother to show up when the stadium was demolished in 2010.

“When that information came to our attention we batted it around, but we were all convinced in the end that this guy was not reliable,” FBI agent Jim Kossler said then. “We were able to prove to our mind that what he was telling us couldn’t have happened because he either couldn’t have been there or he was in jail at the time.”

Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: Hoffa was abducted by ″either federal marshals or federal agents,″ driven to a nearby airport and dropped out of a plane, possibly into one of the Great Lakes that surround Michigan.

Who put it forth: Former Hoffa aide and strong-arm Joseph Franco in the 1987 book ″Hoffa’s Man.″

Outcome: Other than Franco’s word, there was nothing to support his claim.

A Chicago Tribune review of the book put it this way: “Former New York Times reporter Richard Hammer, who helped Franco with the book, candidly writes in the introduction that the stories have the ‘ring of truth.’ Maybe, but they also reek of something else.”

Detroit house Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: Hoffa was killed by one-time ally Frank Sheeran at a Detroit house. Key parts of the narrative became the basis for the 2019 movie “The Irishman."

Who put it forth: Sheeran.

Outcome: Bloomfield Township police ripped up floorboards at the house in 2004, but the FBI crime lab concluded that blood found on them was not Hoffa’s.

Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: New Jersey mob hit man Richard “The Iceman” Kuklinski killed Hoffa in Michigan, drove the body to a New Jersey junkyard, sealed it in a 50-gallon drum and set it on fire. He later dug up the body and put it in the trunk of a car that was sold as scrap metal.

Who put it forth: Kuklinski, who contended in his 2006 book, “The Ice Man: Confessions of a Mafia Contract Killer,” that he received $40,000 for the slaying.

Outcome: The former chief of organized crime investigations for the New Jersey Division of Criminal Justice told The Record of Bergen County, New Jersey, that he doubted the claim.

“They took a body from Detroit, where they have one of the biggest lakes in the world, and drove it all the way back to New Jersey? Come on,” Bob Buccino said.

Pool - HOFFA

Updated

Theory: Hoffa was killed and his body was buried beneath a swimming pool in Bay County’s Hampton Township.

Who put it forth: Richard C. Powell, who used to live on the property and who was serving life in prison without the possibility of parole for a 1982 homicide in Saginaw County.

Outcome: Police used a backhoe to demolish the pool and dig beneath it in 2003, although no trace of Hoffa was found. At one point, police brought Powell to the scene handcuffed and shackled. Then-Bay County Prosecutor Joseph K. Sheeran told the Bay City (Michigan) Times that Powell “didn’t have any connection to Hoffa at all” and that the convict just wanted a few moments of fame.

RENAISSANCE CENTER DETROIT

Updated

Theory: Hoffa’s killers buried him beneath the 73-story Renaissance Center in downtown Detroit.

Who put it forth: Marvin Elkind, a self-described “chauffeur and goon for mob bosses,” in the 2011 book “The Weasel: A Double Life in the Mob.”

Outcome: The building, home to General Motors' headquarters, stands and the claim has never been taken seriously.

Oakland - Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: Hoffa was buried in a makeshift grave beneath a concrete slab of a barn in Oakland Township about 25 miles north of Detroit.

Who put it forth: Reputed Mafia captain Tony Zerilli in the online “Hoffa Found.” Zerilli was in prison for organized crime when Hoffa disappeared, but he claimed he was informed about Hoffa’s whereabouts after his release.

Outcome: The FBI and police in 2013 spent two days digging at the site that no longer had the barn, but found nothing.

Landfill Hoffa Search Theories

Updated

Theory: Hoffa’s body was delivered to a Jersey City landfill in 1975, placed in a steel drum and buried about 100 yards away on state property that sits below an elevated highway.

Who put it forth: Journalist Dan Moldea, who has written extensively about the Hoffa saga, as a result of interviews with Frank Cappola. Cappola, who died in 2020, says his father owned the landfill and buried the body.

Outcome: To be determined. The FBI obtained a search warrant to do a site survey, which it completed last month and is analyzing the data. The agency hasn't said whether it removed anything from the site.