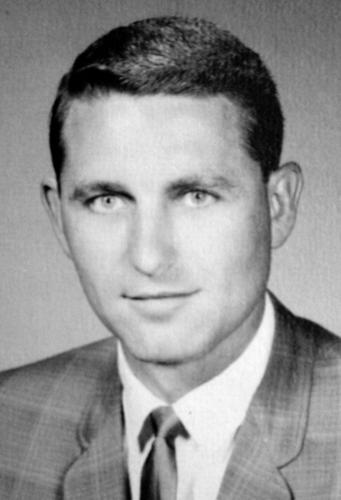

After Huntington Beach School District superintendent Max L. Forney hired Woodrow Smith to be the principal at the dazzling new Marina High School in 1964, they refined their search for a basketball coach to two young teachers — Lute Olson and John Kasser.

Olson, 30, had spent two years as an assistant coach at nearby Western High School, working under big-name basketball coach Roy Stevens; at the time, Olson was the head coach at new Loara High School near Disneyland. Kasser, 27, had been an assistant coach at Downey High School.

After Olson and Kasser went through the interview process, Forney decided to hire Olson and told him as much.

But Smith, the principal, wanted to hire Kasser and told him he would be Marina’s first basketball coach.

After a few days of confusion and anxiety, Forney prevailed. He told his principal that Olson would be Marina’s coach and that he would find another position for Kasser — which ultimately turned out to be head coach of the soon-to-be-built Fountain Valley High School, also in the Huntington Beach district.

Rather than fear his rival, Olson hired Kasser as his assistant coach.

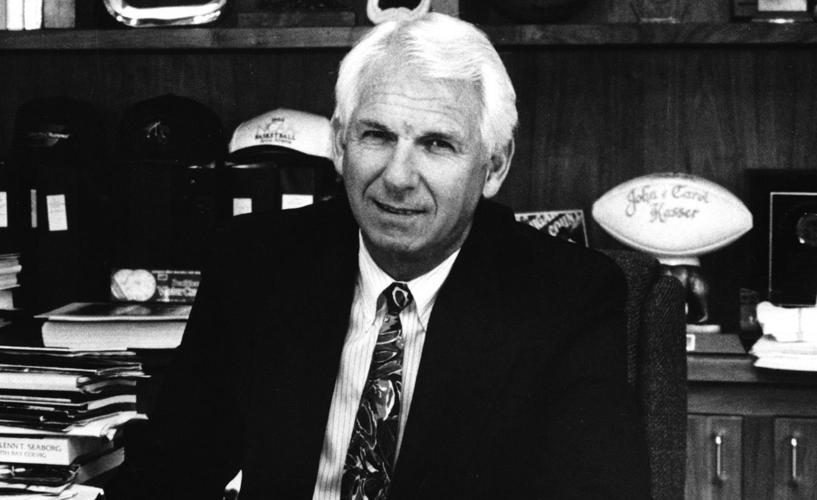

Decades later, the old coaching associates, Olson and Kasser, would get together for dinner during Final Four weekend. Olson was the celebrated head coach at Arizona; Kasser was the athletic director at Cal.

“Lute and John would always talk about those days at Marina High School,” remembers former Arizona athletic director Cedric Dempsey, who, coincidentally, hired Kasser to be his lead assistant during Dempsey’s tenure as athletic director at the University of Houston. “They’d talk about the big meeting when the superintendent and principal realized they had hired two men for the same coaching job.”

Kasser and Olson almost could’ve passed for twins. Both were about 6 feet 4 inches tall and former college basketball players — Olson at Augsburg College in Minnesota and Kasser at Pepperdine. Both were handsome men with striking silver hair.

“John told me that once at the Phoenix airport someone came up to him and said ‘Coach Olson, would you sign an autograph?’” Dempsey says now. “They both were very successful, obviously. But it’s sad in the respect that John died in May and Lute died a few months later. You sometimes wonder what would’ve happened had the superintendent listened to his principal and hired John instead of Lute. Would his career have turned out differently?”

In the ’60s, high school basketball coaches were at the mercy of the school’s neighborhood population. Your players were those who grew up down the street and walked through the door, sometimes unannounced and unknown. There was no open enrollment, no recruiting.

As it turned out, Fountain Valley became known for its swimmers, gymnasts and wrestlers. Marina was a hub of basketball talent. By 1969, Kasser had left coaching to work in the front office for Chevrolet. The same year, Olson was hired to be the head coach at Long Beach City College.

Kasser became an administrator. Olson became a Hall of Fame coach.

“I’m not surprised Lute stuck with coaching and became one of the best ever,” says Dale Brown, who coached LSU to the Final Four in 1981 and 1986 and recruited Shaquille O’Neal to the school in 1990. “He was the epitome of a good teacher, a good coach. You couldn’t intimidate him. He never bragged. He didn’t cheat.

“Many times, the key to being a successful coach is just sticking with it, especially when you’re young, getting your foot in the door. My goodness, I don’t know Lute’s full history, but I know he started as a high school coach in some remote Minnesota schools before he ever went to California. Persistence pays off in this business.”

How would Dale Brown know?

In the winter of 1951-52, he and Lute Olson were the two dominant high school athletes in North Dakota. In a small state like that, it didn’t take long for Olson and Brown to become familiar with each other even though they grew up about 200 miles apart — Brown in Minot, playing at St. Leo High School, and Olson in Grand Forks, at Central High School.

Now 84 and retired in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, Brown hasn’t forgotten that Olson-led Grand Forks team in the 1952 Class B state championship game.

“Lute was a rock, and they beat us in the finals,” Brown told me last week. “I still remember he wore jersey No. 24. He was tough.”

But the high school rivals forged a forever friendship, much like Olson and Kasser did years later.

When Olson was inducted into the Scandanavian-American Hall of Fame in Minot, North Dakota, in 2010, Brown was asked if he would introduce his former prep rival at the banquet.

“As we sat at the dinner table that day, talking about the old days, I reminded Lute that we always called him ‘Luke,’” Brown says. “He told me that it stemmed from his high school baseball coach calling him Luke. It was because their shortstop’s name was Duke, and the coach kept referring to his ‘Duke to Luke’ combination. Either way, Luke or Lute, people came to remember him.”

Olson didn’t forget the path he traveled. He talked with reverence about his days at Iowa, 1974-83. He cherished telling stories about driving from Huntington Beach to the UCLA campus — a drive through manic traffic that could take more than an hour each way — just so he could watch John Wooden coach the Bruins during a practice.

Olson’s legacy will not only be tied to Tucson, but to Iowa City and to Huntington Beach and to Grand Forks.

About 30 years ago, 1940s Iowa high school basketball coach Leonard Gibbs moved to Tucson to be with his daughter, Jane Neve, a schoolteacher married to John Neve, minister at the Catalina United Methodist Church.

“My dad was a classy gentleman like Lute,” Jane Neve says. “He never swore. He always wore a coat and tie.”

One day, Gibbs and John Neve met Olson while the men were getting a haircut from the same Tucson barber. Gibbs related his stories of coaching at small Hopkinton High School in rural Iowa. He rattled off a list of Olson’s accomplishments with the Iowa Hawkeyes and told him, year by year, the name of Iowa’s key players.

Olson engaged and befriended Neve and Gibbs, then in his 90s. They met several times over the years, sharing their Iowa experiences.

“When dad passed away in 1995, I let Lute know,” Jane remembers. “And, yes, he sent me a handwritten note.”

A day or two after Olson died, John Neve drove to McKale Center and stood by Olson’s statue. The coach is gone, but he won’t be forgotten.