Ruth Seawolf had millions in her hands and let it slip away.

It started with a phone call the Silver City, New Mexico, real estate agent received a few months back.

The gentleman on the other end said his aunt — her name has not been disclosed — had died and he wanted to sell her house. But first, it was loaded down with her possessions.

“Ruthie,” Seawolf recalled him saying to her, “go through the house and take what you want.”

The first thing she noticed when she opened the door was the artwork.

“There were hundreds of paintings in the home,” said Seawolf.

One of the paintings she picked up and looked at was “Woman-Ochre,” a Willem de Kooning piece stolen from the University of Arizona Museum of Art in 1985. The museum won’t say what its worth is, but it was valued at $400,000 when it was stolen, and when the UA tried to revive interest on the theft’s 30th anniversary, a news release said the piece was worth up to $160 million. A little more than a decade ago, another de Kooning painting in the “Woman” series sold for $137.5 million.

Seawolf did not know that, of course. And she wasn’t interested in taking the piece by one of the giants in the 20th century abstract expressionism movement.

“Did I like it? Honestly, no,” she said in a phone interview Friday. “It was kind of funky.”

She connected the seller to David Van Auker, owner of Silver City’s Manzanita Ridge Furniture and Antiques, who arranged to purchase some of the home’s contents.

Among those was the de Kooning oil.

And the painting began its journey back to where it belonged.

“It really is thanks to a good citizen, David,” said Meg Hagyard, the interim director of the UA Museum of Art.

“We owe him such a huge debt of gratitude.”

A few people pointed out to Van Auker that the painting looked like an original, so he began to research the piece, coming across articles about the theft.

By Thursday, Aug. 3, he was pretty sure he had the real deal and called the UA museum.

It didn’t waste any time. Hagyard and a few other museum employees were in Silver City the following Monday.

And they were inclined to agree with him: This was the de Kooning that was stolen the day after Thanksgiving 1985.

“We’ve done preliminary authentication, but we feel very, very confident,” said Hagyard. “We are taking further steps to authenticate it, but we are confident.”

There is restoration that needs to be done on the painting, as well. Hagyard said they do not know yet when they will be able to put the piece back on display.

Artist Josh Goldberg remembers well the morning the art was stolen.

He was the museum’s director of education. He had the day off, but the mother of a young student called. She had an art project. Could he help?

Goldberg arranged to meet the two before the museum opened.

As he walked up to the main entrance, he noticed a man and woman sitting on the bench, waiting for the doors to open to the public.

“I looked over at them and I thought there was something odd about them,” Goldberg recalled.

“Something struck me as kind of funny. The man was very slim and had his hair slicked back and a moustache. The guy looked too effeminate, and the woman just the opposite, kind of masculine.”

After he helped the student, he stepped into the washroom before he left.

“That’s when I heard the guard screaming,” said Goldberg. “I thought he had fallen down the stairs or had a heart attack.”

Goldberg ran out.

“It’s gone, the painting’s gone,” said the panicked guard.

They both ran out the front entrance, the guard going one way, Goldberg the other. But it was too late; they, and the de Kooning, were gone.

“It was a sickening feeling,” he said about looking at the place where the painting once was, sloppily cut away from the frame.

“But then it made me really angry. I would often teach from the museum’s collection, and that’s one of the ones I would teach from. It really bothered me that people could no longer learn from it.”

Lee Karpisack, the curator of the museum at the time, recalls how devastating the theft was.

“It was so difficult to go upstairs and know you’d see the painting gone,” she said. “It was so sad.”

UA Chief of Police Brian Seastone was a corporal with the campus police at the time, and was assigned to the case.

“It was a Friday morning right after the museum opened up,” he recalled.

“Two individuals — a man and a woman — walked in right at the opening. The woman was talking to one of the office staff there while the gentleman went upstairs. He came down very quickly and they both left. The staff thought it was strange — why would they come and leave so quickly?”

Campus police called the FBI for help, but with no clues to go on, it seemed pretty hopeless. The investigation into the theft continues, and the FBI declined an interview request.

“I asked the FBI agent who would do such a thing,” said Goldberg. “He said something like, ‘There’s always a buyer for art.’ He said it was probably already out of the country and it would never again see the light of day.”

That morning was an emotional one for the staff, Seastone recalled.

“Thirty years ago, I saw the tears of disappointment. There was despair from everyone involved.”

Monday, when the piece returned to the museum, there were tears again, he said.

“A lot of tears of happiness and joy. I felt the same emotion. It was so wonderful to have this home where it should be,” Seastone said.

“This is one of the most extraordinary pieces in the collection,” Karpisack said about the de Kooning. “It completes the collection again.”

Stolen artwork worth as much as $160 million recovered for University of Arizona

Willem de Kooning "Woman-Ochre" Returned to UA Museum of Art

Updated

The recovered painting by Willem de Kooning is readied for examination by UA Museum of Art staff Nathan Saxton (r), Exhibitions Specialist, and Kristen Schmidt, Registrar, on Aug. 8, 2017.

Stolen painting

Updated

David Van Auker, a furniture and antiques dealer in Silver City, New Mexico, can’t hold back his excitement when telling the story of discovering a missing Willem de Kooning painting. Olivia Miller, UA Museum of Art curator, looks on.

Stolen painting

Updated

Willem de Kooning’s “Woman-Ochre” was found in New Mexico after being stolen in 1985 from the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Stolen painting

Updated

Willem de Kooning’s “Woman-Ochre,” on display for a news conference on Monday, has been returned to the University of Arizona Museum of Art.

Painting recovered

Updated

This undated image provided by University of Arizona Museum of Art shows an oil canvas by artist Willem De Kooning, titled: "Woman-Ochre," 1954-55, a Gift of Edward Joseph Gallagher, Jr." The artwork was stolen 30 years ago from the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson, Ariz.

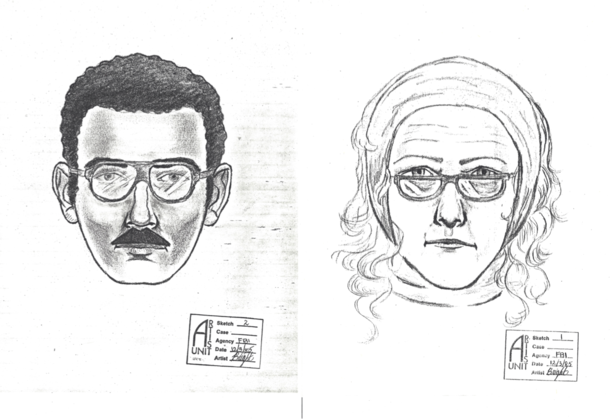

Suspects in art theft

Updated

A Dec. 6, 1985 sketch of the suspects in the theft of a Willem de Kooning painting from the University of Arizona Museum of Art. They were described as a woman in her mid-50s with shoulder-length reddish-blond hair, wearing tan bell-bottom slacks, a scarf on her head and a red coat, and a man with olive-colored skin, wearing a blue coat. Both had thick-framed glasses.

Missing de Kooning painting

Updated

Today, the empty frame still holds narrow edges of the missing de Kooning painting at the University of Arizona Museum of Art in Tucson.