In Nooshie Motaref's unpublished manuscript of Persian fairy tales, the girls run the show.

The women in these stories are not damsels in distress waiting at the top of a tower for the arrival of Prince Charming.

These are take-charge women who merit main-character status.

"In modern days, they are putting Supergirl on TV, but I want to show them that years and years and years ago, in the oral traditions of Persia, they had these stories told by men. They didn't have women storytellers."

And here she is, telling those same stories.

These days, Oro Valley is her home, but once upon a time it was Tehran, Iran, the place she was born. There, she grew up hearing tales of brave and beautiful women — some fictional, some family.

Nooshie Motaref wrote "Tapestries of the Heart" to tell the stories of four generations of Iranian women who loved, lived and endured.

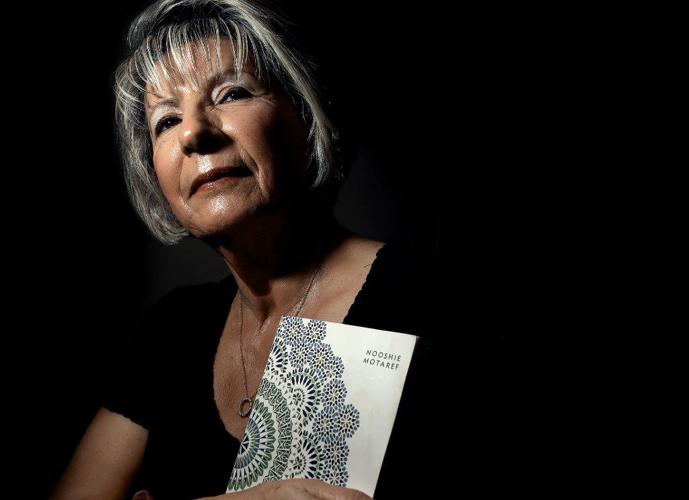

Now in her 60s, these are the tales she tells. After a lifetime of studying stories as a professor of English and folklore, now it's time to tell her own. "Tapestries of the Heart: Four Women, Four Persian Generations," published in 2015, weaves together four narratives of four generations of Iranian women. This is fiction, yes, but really it is Motaref's story, her mother's, her grandmother's, her great-grandmother's.

"I recognize it because it is the story of our life," says Motaref's only sibling, sister Sara Motaref. "Even though she changed the names, oh sure, I recognize it."

"Tapestries of the Heart: Four Women, Four Persian Generations" by Nooshie Motaref.

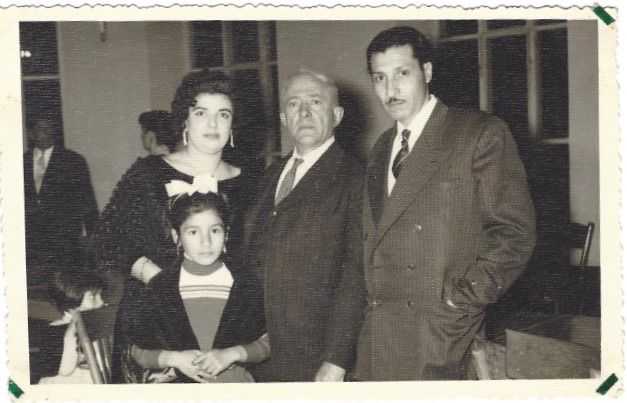

Growing up, the girls spent many hours in the care of their grandmother and great-grandmother. Their mother was a teacher and their father a scholar and newspaperman.

"I told my grandmother one day, 'Oh, I'm so sorry for great-grandma because she is so old and has so many wrinkles,'" Nooshie Motaref recalls. "Then my grandmother said, 'Don't you say that! She was so beautiful that they wanted her for the king!' And that is one of the stories I remember as if it stuck to my head."

Why she chose to leave Iran for good

"Tapestries of the Heart" follows a similar book by Motaref titled "Iran: A Persian Tapestry." Through anecdotal stories and family lore, Motaref chronicles how the lives of women in Iran change over the decades, stretching as far back as 1896, with her great-grandmother's life.

In Motaref's own life the institution of a law requiring women to don headscarves symbolizes for her how life has changed for women in Iran.

Her great-grandmother wore a head covering as Muslim woman. Her grandmother and mother did not. Motaref never did, not even when Iran's 1979 revolution conceived an Islamic government that required women to cover their heads.

She was about 30 at the time and had already studied outside of Iran — first at Heidelberg University in Germany and then at Florida State University, where she received her master's degree in English language and literature.

She returned to Iran and got a job teaching at the University of Tehran.

When the department chair introduced her to her students, he didn't mention her time in the U.S., instead referencing her studies "abroad."

But her students figured it out. Her accent speaking English was different than department professors who had studied in England. Her students threatened her.

"They came to my office one day and started badmouthing me," she says.

The day she got summoned to the president's office, it all ended.

"When I went to his office, he showed me a contract that if I wanted to continue to be a professor and protect my job, I had to sign that contract promising to abide to the its rule, which was covering my head," she says. "I didn't do that, and I walked away."

Her parents worried for her safety when she stated her intent to skip the headscarf.

"I never learned to cover my head; my mother never did; my grandmother never did, so it was like a slap in the face," she says. "It was a bitter pill to swallow, so that's why I left the country."

She wanted freedom, American style.

But getting to the U.S. was easier said than done as the Iranian hostage crisis in the early 1980s unfurled. President Jimmy Carter had announced that the U.S. would not reissue visas or give out new ones to Iranian citizens.

For more than a year, Motaref trudged through a post-doctorate program in Switzerland. Eventually, she was able to transfer her post-doctorate work and return to the U.S., where her younger sister Sara was already studying.

She made a promise with herself that she wouldn't return to Iran as long as the current regime remained.

"It was very hard, but what is more hard is staying and losing my individual freedom for the rest of life...," she says, now an American citizen.

As she sat in the plane, she remembered her father's words: "Whatever we do, that is our fate."

Father knows best

At least in part, Motaref wrote "Tapestries of the Heart" for her father.

"I wanted to be in a free country and tell what I want to tell ... and not worry that somebody is going to come and knock on my door and get me," she says. "I could never say these things in my book in Iran."

That wasn't the case for Motaref's father, who at one point owned a newspaper in Iran. She remembers spending time in her father's library, thumbing through newspapers and children's magazines.

"I remember asking him, 'How come you don't write anymore?'" she says."He put it aside and closed down his newspaper," fearful for his children should he critique the government.

Motaref's parents always encouraged her to pursue her education. She remembers her father telling her as a young woman that she could decide who marry.

"But I don't think you need to marry now," he would add. "Finish up your education."

Motaref attributes her love of learning and climb through the academic world to parental encouragement — an attitude that wasn't necessarily mainstream among parents of her peers.

"He and my mother, they didn't have a son. They had two daughters, so they raised them just as if they were raising sons," Motaref says. "My father several times told me it doesn't matter that I'm a woman. I have to be a human being on my own, to first be able to support myself, that it's never too late to marry and have a family and have kids."

And so she has.

The family name lives on in America

Motaref remembers her maternal grandmother pitying her father. He had no sons, no one to carry on his name, she said.

Her grandmother had married a man who was part of the Qajar dynasty, the second-to-last dynasty before the institution of the Islamic Republic.

Her father, too, came from that family "because if you are from a royal family, you do not want to mix blood," Motaref says.

She married an American, a colleague from Lurleen B. Wallace Community College in Alabama where she taught English and critical thinking.

Their son Matthew carries the name "Motaref" as his middle name. So does Bryan, his 4-year-old son.

"My name is not only carrying on, but it's carrying on in a different culture," Nooshie Motaref says.

Nooshie Motaref poses with her young grandson Bryan, who carries her family name as his middle name.

Following a divorce, Motaref raised Matthew as a single mom for a decade, until marrying again when her son was 15. She lost her second husband to death.

After the divorce, she transitioned professionally, working her way up to a vice president role within the title insurance industry. She would go back to teaching in the future and open a mediation business.

"I had to support him and myself, and that's the reason I went into the business world, because in the business world I could bring more money home than being a professor or a teacher," she says of raising her son.

She married again when her son was 15, but her second husband died. About two years ago she moved to Tucson to be close to Matthew and his family.

Remembering the "land of roses and nightingales"

In her retirement, Motaref reflects.

"It seems like everything bombards me from the past," she says. "Maybe because we have more time as we get old, rather than jumping and doing."

And so she's jotting it down and telling others.

Motaref gives talks about women and Islam and philosophies of the Middle East. Although she does not practice Islam, she wants people to better understand that "people from that part of the world are still human beings, and they want happiness and freedom and unfortunately, they don't have it."

Loydene Lazich of La Quinta, California has called Motaref a friend for roughly 30 years. She has lived much of Motaref's story with her.

"It's very much a story of her journey through life," Lazich says of "Tapestries of the Heart." "I think that it reflects a lot of the upheavals she went through in Iran, and she put it in novel form."

With her words, Motaref is weaving her own life's tapestry.

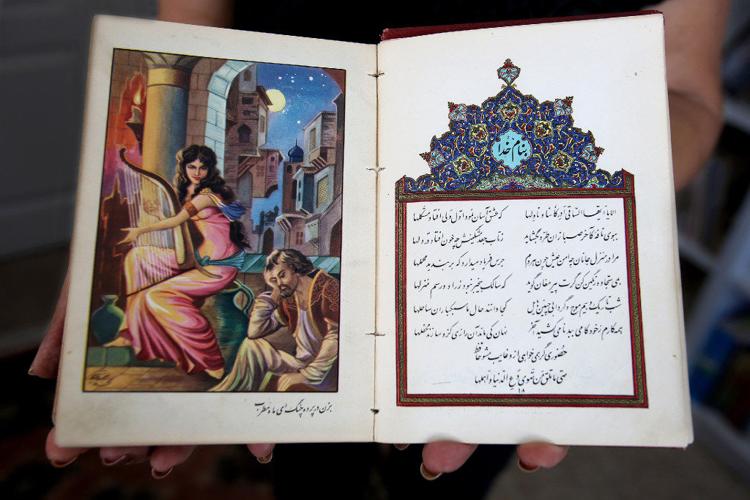

Even the manuscript of Persian fairy tales draws from her own life. For her dissertation at Florida State, where she also received her doctorate degree, she used those same stories to prove Carl Jung's theory of collective unconscious.

The stories also bring to mind another time, another world — "The Land of Roses and Nightingales," as Motaref has titled the seven-story manuscript. She hopes to get it published.

Author Nooshie Motaref holds her copy of a collection of Persian poetry by Hafiz, a Persian poet whose work is referenced in "Tapestries of the Heart." A.E. Araiza / Arizona Daily Star

"As little kids back home, you have the books ... and your parents or your grandparents know all about them and they tell you about (the stories) or read them," says Sara Motaref.

They are stories of strong women, a narrative continued by the women in Motaref's family, a narrative she now shares with readers.

This is what she wants the reader to take away:

"Like a willow in the wind, these women have to go right and left and right and left. Flexible," she says. "This is the story of women who lived, who loved and who endured the life that they had to go through."